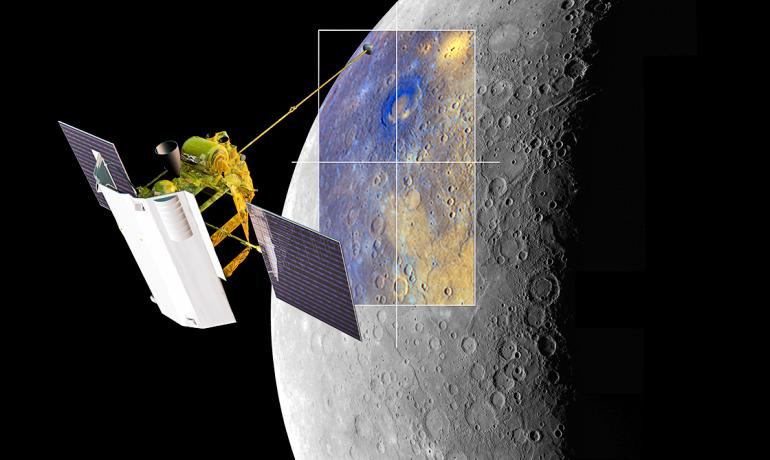

NASA’s Messenger spacecraft has taken the first pictures of ice frozen in dark spots on Mercury, the planet closest to the sun.

The probe, which has orbited Mercury since 2011, snapped shots of water ice and other frozen volatile materials in permanently shadowed craters near the planet’s north pole.

The images provide clues as to when ice formed on Mercury and how it has evolved, according to a study published in the journal Geology. That, in turn, is expected to help scientists figure out more about how water came to other planetary bodies, including Earth and the moon.

“One of the big questions we’ve been grappling with is ‘When did Mercury’s water ice deposits show up?’ Are they billions of years old, or were they emplaced only recently?” says lead author Nancy Chabot, , instrument scientist for MESSENGER’s Mercury Dual Imaging System and a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

“Understanding the age of these deposits has implications for understanding the delivery of water to all the terrestrial planets, including Earth.”

Extreme Temperatures

Mercury is not the hottest planet in the solar system—that honor goes to Venus—but temperatures on the “day” side facing the sun do rise to about 800 degrees Fahrenheit.

But with scarcely any atmosphere to trap heat, the planet plunges to around minus-300 degrees at night. Because the planet rotates around an axis that is not tilted like Earth’s, the sun is never high in the sky at the poles, and some parts of craters never see sunlight at all.

Two decades ago, images from Earth-based radar first revealed the frozen polar deposits, believed to be water ice. That was later confirmed by Messenger—even before the new pictures—with a combination of neutron spectrometry, thermal modeling, and infrared reflectometry.

“But along with confirming the earlier idea, there is a lot new to be learned by seeing the deposits” in the new visible light photos, Chabot says.