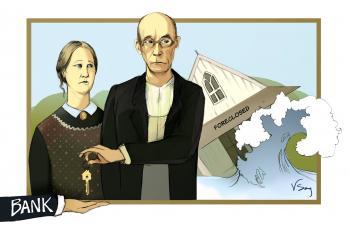

Walking away from a mortgage seemed like a crazy idea to Chris Schreur, a financial adviser, and his wife Valerie thought he had gone mad when he mentioned it. It wasn’t just the financial hit, but the shame of defaulting.

“I think it is the number one reason, by far, that more people aren’t doing this,” Chris Schreur said.

After buying a house during the boom of the mid-2000s, many homeowners are now finding themselves underwater; meaning they owe more than their homes are worth. More than 11.3 million, or 24 percent, of homeowners were underwater by the end of 2009, according to a report by First American CoreLogic.

Finding themselves more than $130,000 underwater on their mortgage, the Schreurs chose to stop making their payments, even though they could afford it. “It was completely crazy to keep throwing good money after bad,” Mr. Schreur said. Their credit score was in the 800s and they had never been late on any payments before then. They owed $430,000 on their California home.

“Objectively the hardest part was the hit to the credit rating,” he said. “Defaulting on a debt is the hardest thing to accept.”

Schreur did some research and found he could get more house for less money by renting.

“My degree is economics, so I understand that you don’t keep putting money into a losing proposition just because you already put money in,” he said.

But it was his child’s future that made the decision clear and helped ease the shame factor.

“I think of it as a choice between either defaulting and writing the debt off now, and potentially not being able to send our daughter to college in 12 years,” he said.

Not wanting to go it alone, Schreur contacted You Walk Away, a company designed to provide information and assistance to those looking to strategically default.

He said they helped him counter a lot of the myths and disinformation that surround mortgage defaults. Schreur said a lot of people are afraid of foreclosure; they equate foreclosure with bankruptcy, or think a bank can take their savings, affect their employment, or their 401ks.

After paying the $1,000 flat fee for You Walk Away’s services, Schreur had access to attorneys who helped stop the pressure the bank was exerting on the family. Once the mortgage payments stopped, the bank had begun to send letters and called Schreur at home and at work.

Schreur said he talked to the bank about a mortgage modification before they started defaulting, but the bank was not interested.

The threats and stigma of defaulting seems to be the coercion banks are using to stop them from defaulting, said Schreur. “So the [banks think] it’s better to go that route than it is to just renegotiate with the people who, all things being equal, would rather stay in their homes.

“I think a lot of people feel stuck,” he said. “You do have choices. Staying in your house is a choice, walking away is a choice.”

The Schreurs are renting a home a mile away from their foreclosed place for $1,000 less per month than their mortgage payments.

“I think it is the number one reason, by far, that more people aren’t doing this,” Chris Schreur said.

After buying a house during the boom of the mid-2000s, many homeowners are now finding themselves underwater; meaning they owe more than their homes are worth. More than 11.3 million, or 24 percent, of homeowners were underwater by the end of 2009, according to a report by First American CoreLogic.

Finding themselves more than $130,000 underwater on their mortgage, the Schreurs chose to stop making their payments, even though they could afford it. “It was completely crazy to keep throwing good money after bad,” Mr. Schreur said. Their credit score was in the 800s and they had never been late on any payments before then. They owed $430,000 on their California home.

“Objectively the hardest part was the hit to the credit rating,” he said. “Defaulting on a debt is the hardest thing to accept.”

Schreur did some research and found he could get more house for less money by renting.

“My degree is economics, so I understand that you don’t keep putting money into a losing proposition just because you already put money in,” he said.

But it was his child’s future that made the decision clear and helped ease the shame factor.

“I think of it as a choice between either defaulting and writing the debt off now, and potentially not being able to send our daughter to college in 12 years,” he said.

Not wanting to go it alone, Schreur contacted You Walk Away, a company designed to provide information and assistance to those looking to strategically default.

He said they helped him counter a lot of the myths and disinformation that surround mortgage defaults. Schreur said a lot of people are afraid of foreclosure; they equate foreclosure with bankruptcy, or think a bank can take their savings, affect their employment, or their 401ks.

After paying the $1,000 flat fee for You Walk Away’s services, Schreur had access to attorneys who helped stop the pressure the bank was exerting on the family. Once the mortgage payments stopped, the bank had begun to send letters and called Schreur at home and at work.

Schreur said he talked to the bank about a mortgage modification before they started defaulting, but the bank was not interested.

The threats and stigma of defaulting seems to be the coercion banks are using to stop them from defaulting, said Schreur. “So the [banks think] it’s better to go that route than it is to just renegotiate with the people who, all things being equal, would rather stay in their homes.

“I think a lot of people feel stuck,” he said. “You do have choices. Staying in your house is a choice, walking away is a choice.”

The Schreurs are renting a home a mile away from their foreclosed place for $1,000 less per month than their mortgage payments.