Further tightening the race for the Indonesian presidency, Prabowo Subianto’s running mate, Hatta Rajasa, appeared stronger in the vice-presidential debates on Sunday night, building on Prabowo’s win over Joko Widodo in the second presidential debate.

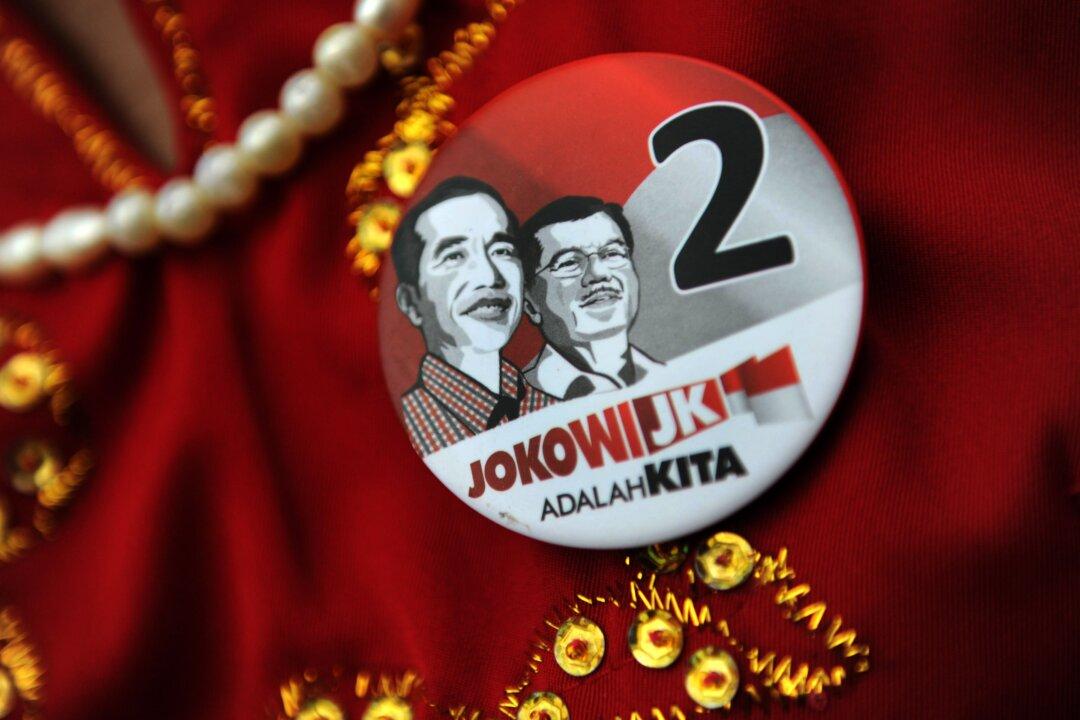

With the election imminent, the former general’s popularity has nearly caught up with his rival, more popularly known as Jokowi.

In the lead-up to election day on July 9, Indonesia’s General Elections Commission (KPU) has scheduled five weekly debates.

With only two candidates running for the presidency, this year’s debates are more divisive than the 2009 debates between Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY), Megawati Sukarnoputri and Jusuf Kalla. We see more die-hard supporters in the audience, chanting slogans for their candidates as if they were barracking for a team in a sporting event.

But the audience’s ample enthusiasm is not a reflection of the quality of debate. Like the past three debates, this one had the same problems: none of the candidates was willing to bear bad news to the people; neither actually discussed real problems.

For instance, during Sunday’s debate on the issue of human resource development and research and technology, Hatta, the chairman of the National Mandate Party (PAN) and coordinating economic minister in SBY’s cabinet, attacked Jokowi-Kalla’s opposition to the national exam. Kalla, who once served as SBY’s vice-president, responded by stressing they would evaluate the national exam, not abolish it.

None of them, however, discussed the real mess behind the issue, notably the high number of students passing the exam. This may sound counter-intuitive, but considering the poor quality of Indonesian teachers in remote regions, which both candidates acknowledged, it is simply mind-boggling that 99% of high school students in Indonesia passed the exam.

Similarly, when the moderator asked their solution to stop the “brain drain” from Indonesia, both candidates proposed better compensation to keep skilled workers from leaving the country. They ignored the fact that many of these people were leaving out of frustration at having to deal with red tape and being unable to work in an environment where corruption, collusion and nepotism are rampant.

In general, both vice-presidential candidates were saying the same things, albeit in different ways. They agreed that the government needed to give more funding to education and technological research, as well as provide incentives for private sector research. They agreed that the brain drain should be stopped. They also agreed that the government needed to attract talents back to the country and pay them attractive compensation so they would stay.

So who won Sunday’s debate? Honestly, it was so boring that it was difficult to pay attention to the arguments. While Kalla was a favourite due to his aggressive style, this time Hatta won – though barely – on the point of substance.

If we were keeping scores, the fourth debate would bring the rivals to a draw. Jakarta governor Jokowi owned the first debate, as he managed to shed doubts about his leadership capability. At the same time, Kalla managed to put Prabowo, the former special forces unit commander, on the defensive with his questions on the issue of human rights.

Jokowi also overall won the third debate on foreign policy and national security. He brought up the issue of Australia-Indonesia relations in the debate. Jokowi looked in control despite a lack of substance from both candidates in their answers. Jokowi even managed to insert a jab at his detractors, that he could be decisive if needed.

Prabowo performed better in the second presidential debate. Discussing economic development and social welfare, he attacked Jokowi’s programs right from the start.

Jokowi looked unprepared for the aggressive questionings in the second debate. Even though he managed to stage a comeback, the overall impression of the debate was that Prabowo won the match and Jokowi was unable to maintain his momentum.

The fifth debate, which will again be between the two presidential candidates and their running mates, hopefully will be far more interesting than Sunday’s debate. With Jokowi and Kalla again able to run as a pair, they should be a formidable team. Prabowo and Hatta might need to press ahead aggressively if they want to catch Jokowi-Kalla flat-footed.

Despite all the excitement about the debates, they have done little to highlight the issues at stake or show the differences between the candidates. Rather, the debates merely serve to energise the candidates’ bases, giving them soundbites to use to show how good their candidates are in public speaking.

Yohanes Sulaiman does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.