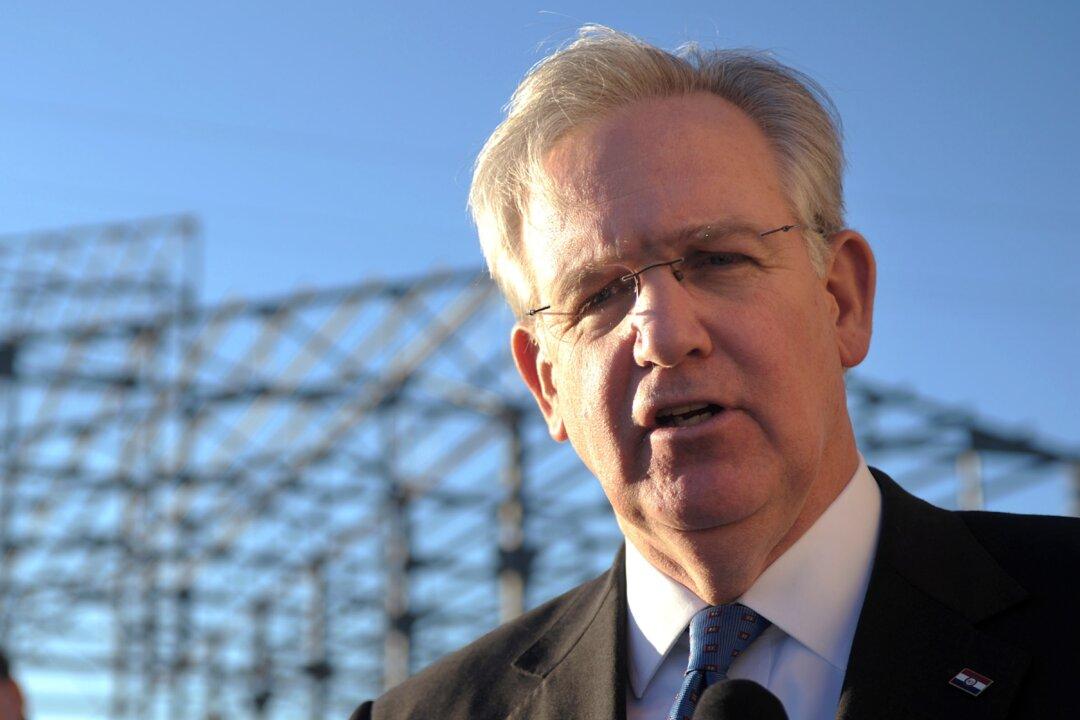

JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. — Democratic Gov. Jay Nixon vetoed a measure Thursday that would have made Missouri the 26th right-to-work state, and it’s unclear whether proponents will be able to muster enough support in the Republican-led Legislature to override the veto.

The governor, a longtime opponent of the effort, traveled to the Kansas City area to announce the veto among about 200 local United Auto Workers union members near a Ford assembly plant. The bill would have barred workplace contracts that require all employees— even those who aren’t union members — to pay union fees.

“This extreme measure would take our state backward, squeeze the middle-class, lower wages for Missouri families, and subject businesses to criminal and unlimited civil liability,” Nixon said in a statement. “Right to work is wrong for Missouri, it’s wrong for the middle-class and it must never become the law of the Show-Me State.”

The legislation also would make anyone “who directly or indirectly violates” its provisions subject to misdemeanor charges punishable by up to 15 days in jail and a fine of up to $300. Civil lawsuits also could be brought against anyone who violates, or threatens to violate, the bill’s ban on mandatory union fees in workplaces.

Nixon slammed the bill as a “big-government overreach.”

Most of the Missouri’s eight neighboring states already have right-to-work laws; the only two that don’t are Illinois and Kentucky. Republican legislators and governors in the Midwestern states Indiana, Michigan and Wisconsin all enacted right-to-work laws in the past three years.

Supporters in Missouri say the legislation would attract businesses and spur economic growth, citing lawmakers’ failure to pass a law as an incentive for companies to instead expand in nearby right-to-work states. Reviews of research into the economic effects of right-to-work laws have generally concluded that it is difficult to isolate that provision from other policies and preferences in the state.

“Missouri is at an economic disadvantage that must be reversed,” Republican Lt. Gov. Peter Kinder said in a statement. “Missouri has a well-trained workforce and great resources, but we have been told time and again by site-selection consultants that companies pass over non-right-to-work states, no matter their qualifications.”

Others tout the measure as a matter of fairness for workers who now can be forced to pay fees even if they don’t want to join a union.

Critics argue it would weaken unions by creating a free-rider system and could lead to lower wages.

“If enough members opt out of paying union dues, they’re able to basically get the benefits of belonging to the union for free,” said Jason Starr, 39, a team leader at Ford’s Kansas City Assembly Plant. He said that “would essentially weaken the ability of the union to function.”

This year marks the first that Missouri legislators were able to foster enough support to send a bill to the governor, and it came at a cost. The Legislature effectively shut down the last week of session after some GOP senators forced a vote on the measure, and Democrats in response filibustered for days. Only one other bill was passed in the Senate.

Even with a record number of Republicans in the Missouri House and a near-record in the Senate, the bill’s original passage still fell short of the two-thirds majority vote that would be needed in both chambers to overturn Nixon’s veto. The GOP was split, with some members joining Democrats in opposition. Senate President Pro Tem Tom Dempsey, the top Republican in that chamber, was among those who voted against right to work.

While bill sponsor Rep. Eric Burlison, R-Springfield, said in a statement that he’s “optimistic” fellow representatives will join him in an attempt to override the veto, House Minority Leader Jake Hummel of St. Louis said Democrats are “confident” such efforts would fail.

The measure passed 17 votes short of what’s needed to override a veto in the House.

Legislators are to reconvene in September to consider overriding vetoes.