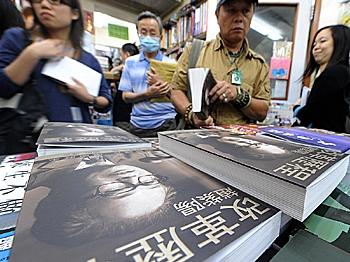

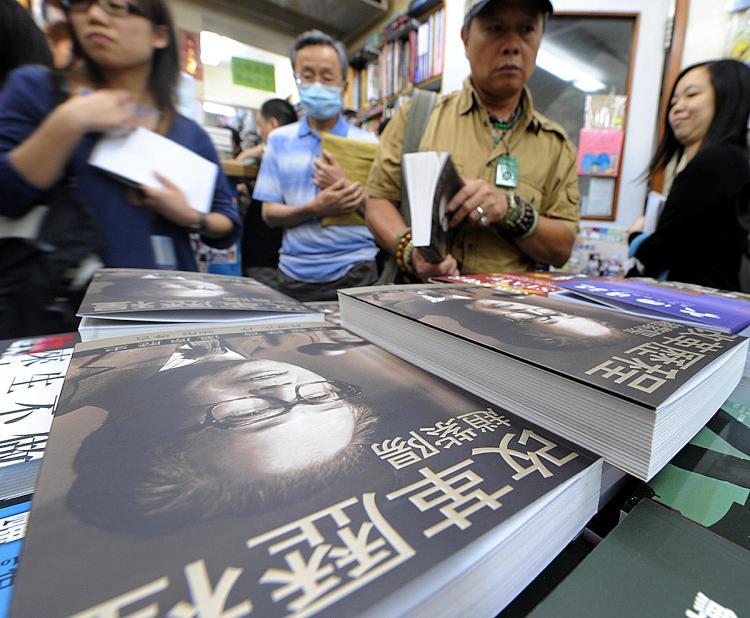

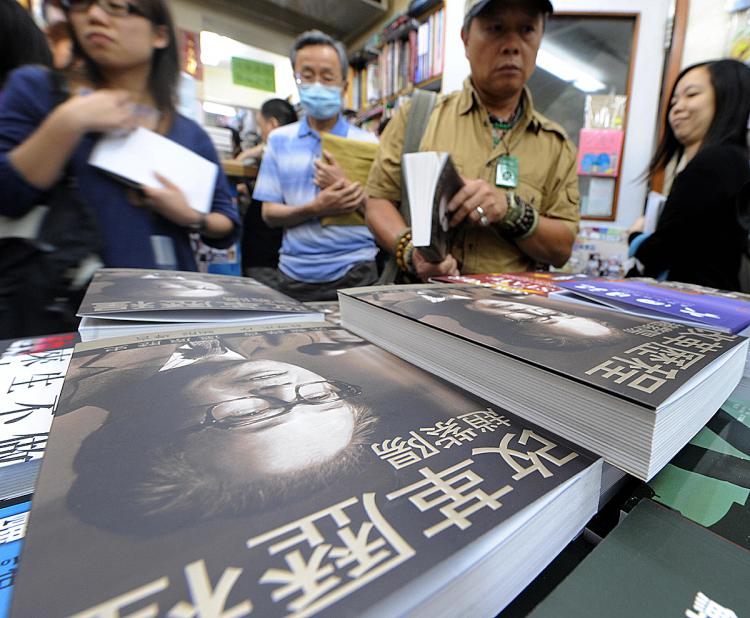

We met with Bao Pu, editor of the recent best-seller, Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Zhao Ziyang, to discuss the significance of the publication.

“It took two and a half years to [obtain] the material ... Every communication was not done in any electronic form; no phone calls, no email, and I had no direct contact with anyone who was directly involved with the material,” Bao explained.

Bao Pu is the son of Zhao Ziyang’s former policy secretary and the owner of a small publishing company in Hong Kong. Shortly after Zhao’s death in 2005 he became aware of tape recordings that Zhao had secretly made while under house arrest. Feeling the importance of the memoirs and the need to make them public, Bao undertook the task of bringing them to print. Although the project ultimately succeeded, he felt the threat of persecution from Beijing throughout the process.

Hong Kong’s proposed Basic Law Article 23, which the communist regime pushed for but failed to get passed in 2003, demonstrated this threat clearly, says Bao. “If Article 23 in Hong Kong had passed then I’d have to consider the possibility that after this book had been published that the publishing house would be persecuted, and I’d be persecuted in Hong Kong,” he said.

Article 23 attempted to prohibit “any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People’s Government,” along with outlawing certain forms of political organization. Such definitions are often given opaque and arbitrary interpretations in China.

Zhao’s memoirs are an “essential read” for anyone involved or interested in China, says Bao. It reveals the process of how China shifted from a planned economy to a market economy. It also reveals that Zhao, rather than Deng Xiaoping, was the main instigator behind this transformation. During the 13th Communist Party Congress, Zhao had proposed a package of both political and economic reforms. He had proposed that China move from “ruled by men”—in other words, the Communist Party—to “rule of law.” His proposal was rejected however, and to this day the Chinese regime continues to operate outside the law, according to observers.

“His political experience shows the world how the reformers tried to bring about political changes and failed. [The] market economic reform was in parallel to an attempt to do political reform. One succeeded, the other failed. The end of the debate reveals a system of authoritarian hypocrisy.”

Near the end of the book Zhao suggests that, in his view, the best political system currently available in the world is western-style democracy. He saw no future with China’s current political system, as his experience showed him that economic progress cannot lead to political change in the communist regime.

“If a country wishes to modernize, not only should it implement a market economy, it must also adopt a parliamentary democracy as its political system. Otherwise, this nation will not be able to have a market economy that is healthy and modern, nor can it become a modern society with a rule of law. Instead it will run into the situations that have occurred in so many developing countries, including China: commercialization of power, rampant corruption, a society polarized between rich and poor,” Zhao says.

The Chinese regime has not yet commented on the book’s publication, the first ever first-person account from within the Chinese leadership. Public response within China has been very positive, says Bao.

“I got a lot of request from mainland China for copies,” says Bao. “A lot of them told me that they’ve downloaded it from the Web.”

Bao expects that the book will have a lasting effect and help to cause changes within China, starting with the academic and intellectual community.

“The book serves as a restoration of history, once this version of history is in the public domain and receives a lot of attention, it’ll be very difficult for future historians working on the official version of history to ignore this. From this point of view, it has an evolutionary impact for sure.”