As we approach the fifth anniversary of the Arab Uprisings, it’s hard to remember the days of popular protests, of democratic revolutions, and of dreams of a better future that rocked the Middle East in 2011. Nearly five years on, tensions between rulers and the ruled have exploded across the region—and the ensuing struggles for survival have continued to take all manner of ugly forms.

At the center of things, the Syrian conflict has deepened—and while the brutality of Islamic State (ISIS) has been responsible for much of the recent chaos and tragedy across Syria, the regime of Bashar al-Assad has been responsible for seven times as many Syrian deaths as ISIS. Assad’s position was strengthened by continued support from Russia, Iran, and Lebanon’s Hezbollah, antagonizing powerful states in the West and the Gulf—particularly Saudi Arabia. The Gulf states also faced domestic threats from ISIS, with the group carrying out a number of attacks on Shia sites and communities across the region.

The Syrian conflict became ever more internationalized in 2015. The number of foreign fighters on the ground—on all sides—continued to grow, while on the diplomatic level, the Vienna talks tried to resolve the seemingly intractable conflict—though they have yet to yield any decisive action.

The task of dealing with ISIS was further complicated by a batch of new wilayats, groups who declared allegiance to ISIS. Wilayat Sinai in particular was purportedly responsible for a range of acts, allegedly including a massive bomb attack in Cairo and the downing of a Russian passenger jet over Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula.

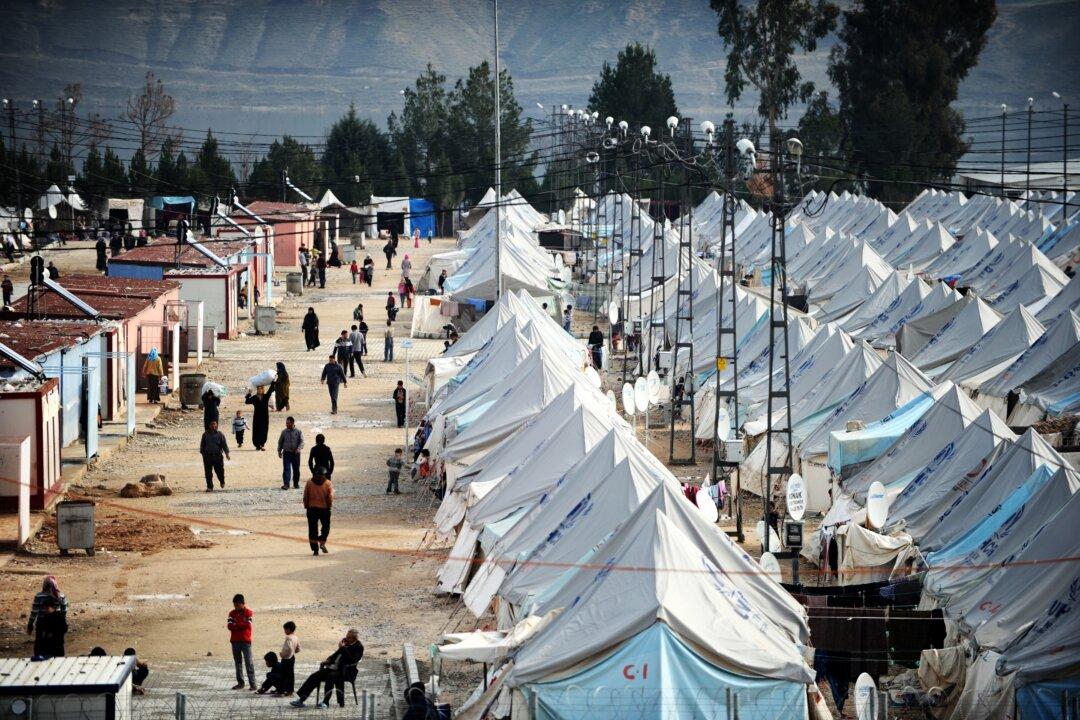

All the while, Syria’s refugee emergency has now escalated to a point that United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon referred to it as the worst humanitarian crisis of our time. It has now killed more than 200,000 people, displacing 7 million within the country and driving more than 4 million to flee abroad.