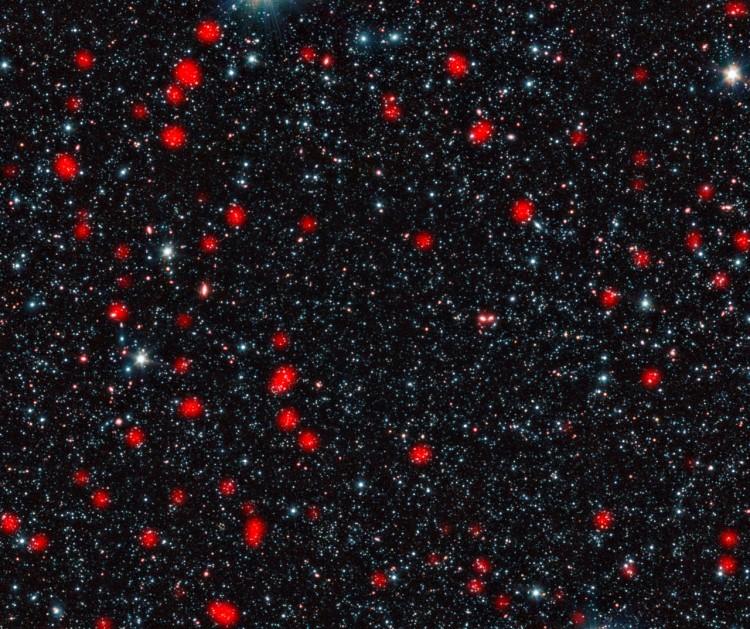

Extremely distant elliptical galaxies have been observed as they were about 10 billion years ago undergoing intense star formation. The galaxies’ star formation, however, mysteriously stopped, turning them into the most massive, but passive, galaxies full of aging stars in the present day.

Astronomers believe the galaxies’ starbursts may have ended when supermassive black holes emerged at the centers of associated quasars. Quasars are highly active, bright objects that emit strong bursts of radiation.

Using a combination of data, including observations from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, the international team found that these galaxies are closely clustered together with giant halos of dark matter—material that cannot be seen, but is believed to constitute more than 80 percent of the universe’s mass. The scientists measured the masses of these halos, and simulated their growth over time using computer models.

“This is the first time that we’ve been able to show this clear link between the most energetic starbursting galaxies in the early universe, and the most massive galaxies in the present day,” said team leader Ryan Hickox at Dartmouth College, N.H., in a press release.

The starbursts lasted only for about 100 million years, but the number of stars in these galaxies doubled during this relatively short period of cosmological time.

“We know that massive elliptical galaxies stopped producing stars rather suddenly a long time ago, and are now passive,” said study co-author Julie Wardlow at University of California–Irvine in the release.

“And scientists are wondering what could possibly be powerful enough to shut down an entire galaxy’s starburst.”

The results suggest that the galaxy clusters were associated with quasars during their active period, with the starbursts sending large amounts of matter into the quasars’ black holes. Subsequent emissions of energy from the quasars could have depleted gas in the galaxies, which is required for star formation, thus cutting their evolution short.

“In short, the galaxies’ glory days of intense star formation also doom them by feeding the giant black hole at their center, which then rapidly blows away or destroys the star-forming clouds,” concluded co-author David Alexander at the U.K.’s Durham University, in the release.

The findings will be published online in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society on Jan. 26.