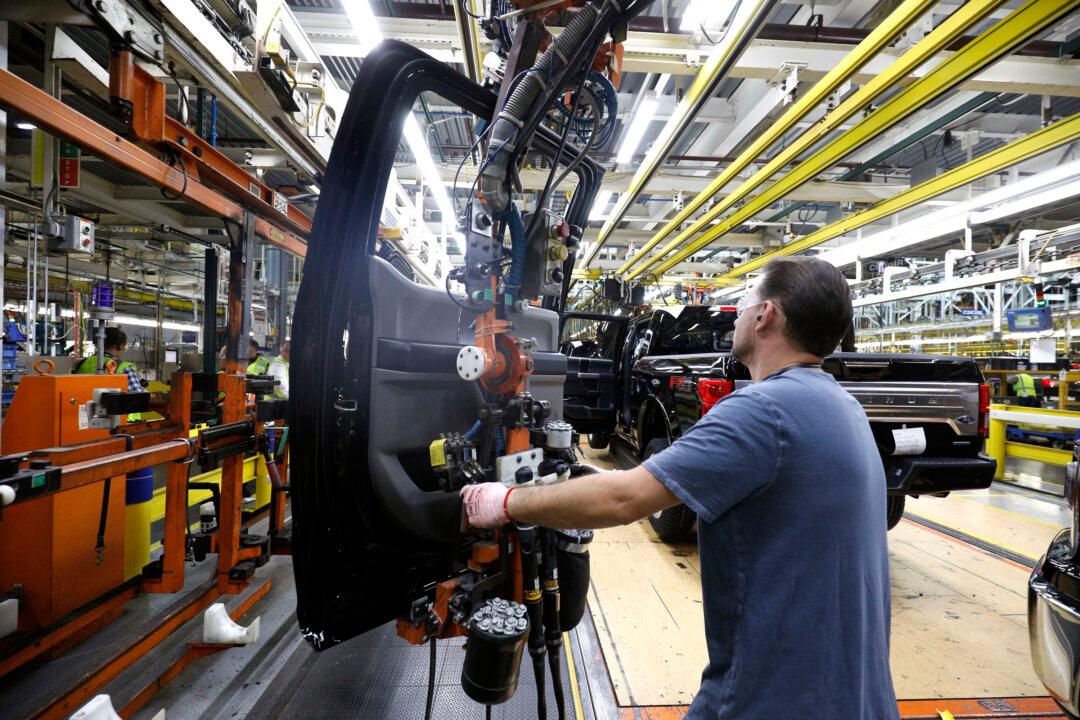

WASHINGTON—The pandemic has exposed the fragility of global supply chains, with the latest disruption being a global shortage of computer chips that has forced some automakers to cut or halt production.

Western governments are learning hard lessons from these disruptions, pushing to create more resilient and diverse supply chains. The Biden administration has pledged to take “immediate actions,” including potentially providing incentives for domestic production.