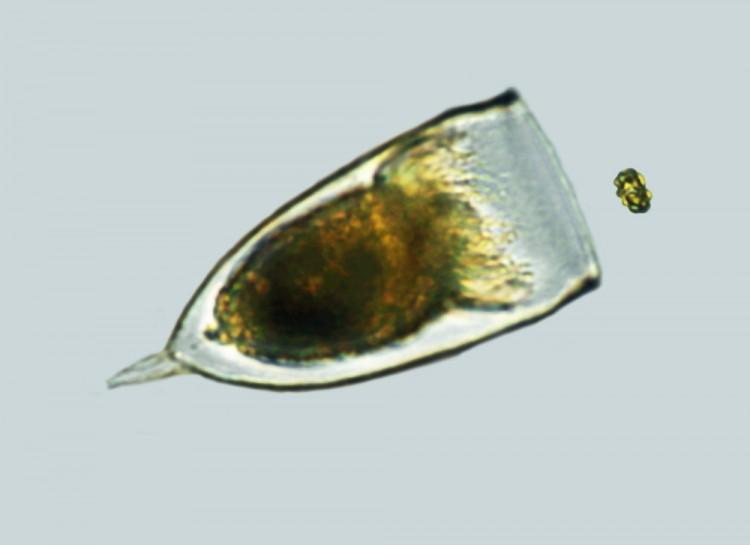

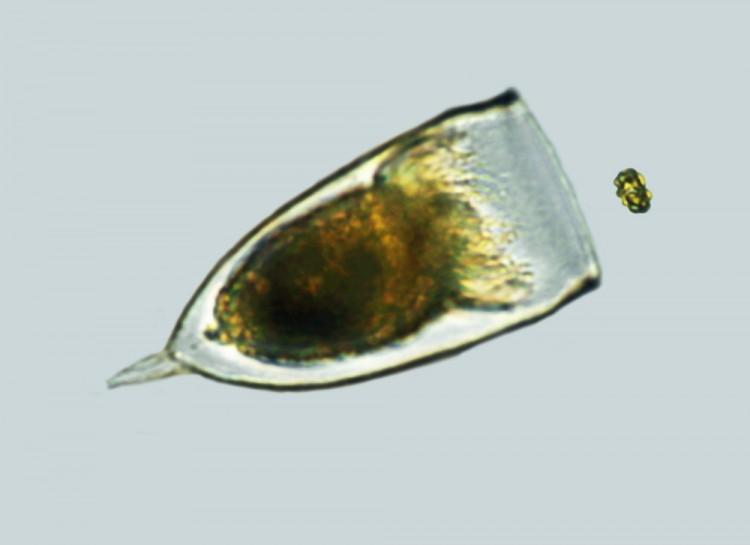

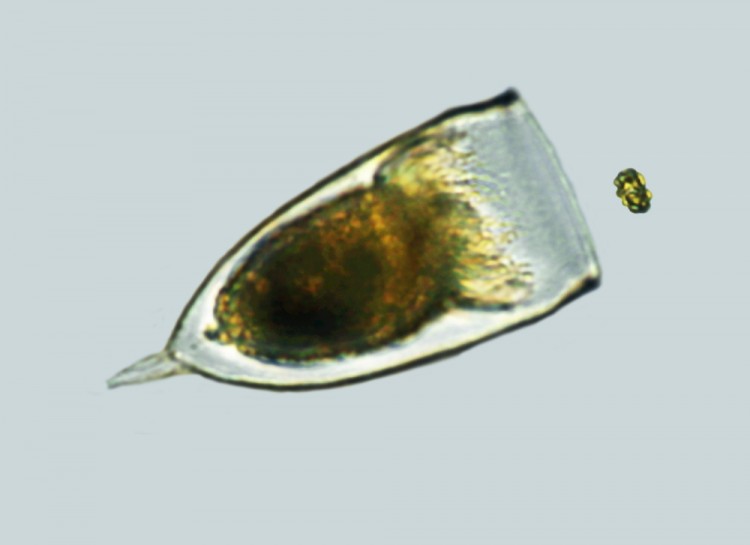

A species of phytoplankton called Heterosigma akashiwo avoids predators, especially when the predators are actively grazing.

Two U.S. scientists studied the 3D movements, population distributions, and survival rates of this microscopic marine plant relative to the predatory zooplankton Favella sp.

The researchers noticed that groups of the algae shifted their distribution away from the predators. The plants also moved away from water that had contained the predators.

“The phytoplankton can clearly sense the predator is there,” said study co-author Susanne Menden-Deuer at the University of Rhode Island in a press release.

“They flee even from the chemical scent of the predator but are most agitated when sensing a feeding predator.”

When the phytoplankton were offered a patch of water with low salinity that the predators cannot tolerate, the plants moved into it.

The team found that this fleeing behavior significantly improved the plants’ survival. Some phytoplankton blooms appear in the ocean suddenly, and cannot always be explained by nutrient availability and growth.

“Our observation of algal fleeing from predators is another mechanism for how blooms could form,” said Menden-Deuer. “Amazingly, looking at individual microscopic behaviors can help to explain a macroscopic phenomenon.”

The researchers hope to observe these behaviors in the ocean environment and study the plants’ genetics.

“If it is common among phytoplankton, then it would be a very important process,” Menden-Deuer concluded. “I wouldn’t be surprised if other species had that capacity.”

The findings were published in PLOS ONE on Sept. 28.

Read the research paper here.

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.