Americans connect Nelson Mandela with Martin Luther King, but according to one historian, Mandela has more in common with George Washington.

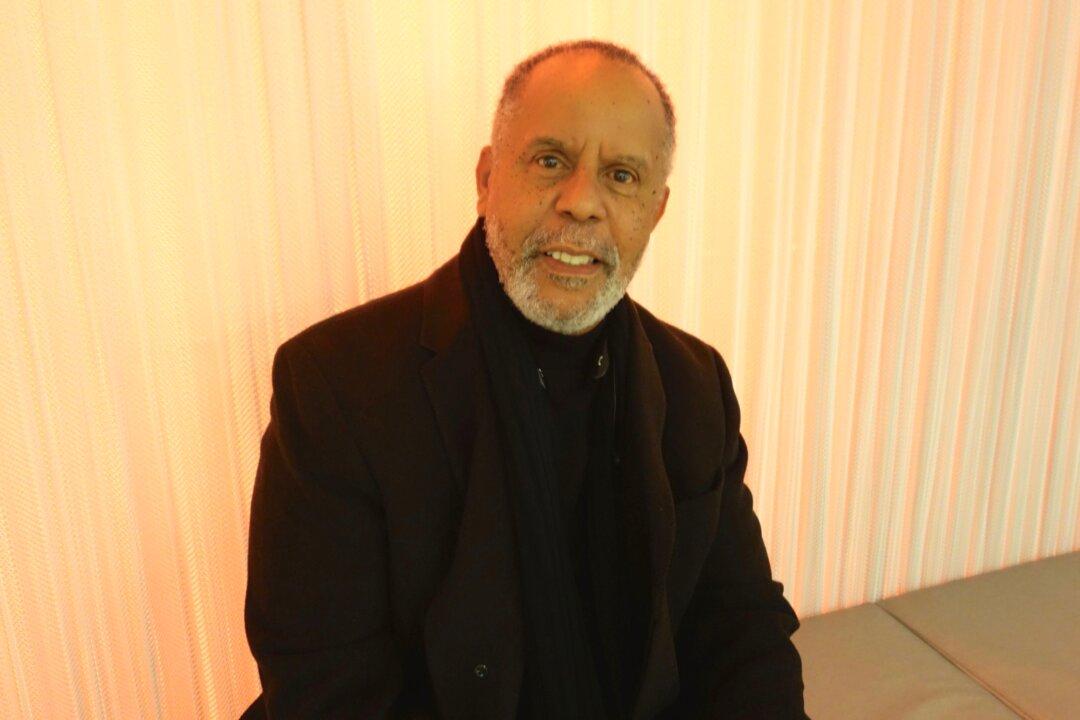

Washington was almost universally loved and revered, and so was Mandela. “There are many people who will deeply mourn him, but hate the ANC (African National Congress),” said John Mason, associate professor of African history at the University of Virginia.

South Africans celebrate Mandela. In the early mornings, workers who pass a large statue of Mandela in a courtyard at Sandtown Mall in Johannesburg customarily pause at the statue to thank him for what he did for their country.

The end of white minority rule could have devolved into bloody chaos or a new dictatorship, but it did not. Mandela’s wisdom and forbearance is credited for that.

Like Washington, he set the course for his emerging country, according to Mason.

“In a lot of ways the first gets to shape the office,” he said. Mandela made a commitment to the rule of law, to a vigorous press, and to free speech. He believed in parliamentary procedure, that “You don’t cling to power.”

Washington retired from office after two terms, a precedent that stayed until Franklin D. Roosevelt. Mandela also retired, when, like Washington, he could have stayed in office for life, said Mason.

Mandela applied his greatest wisdom to pulling the country together after he was elected president in 1994, according to Mason.

He knew he needed to become a symbol around which all the people of South Africa could gather. He made a series of gestures, drinking tea with the widows of Afrikaans leaders, using Afrikaans words in his speeches, and supporting the Springboks rugby team, said Mason.

Though South African philosophy influenced the American civil rights movement, Mandela had a different approach to nonviolence than King had, according to Mason.

The two nations have a unique connection. Apartheid was modeled on the practices of the Jim Crow South, and the nonviolent tactics of the American civil rights movement were partly inspired by the South African ethic, Ubuntu, which could be roughly defined as a humanistic worldview embracing generosity.

Mahatma Gandhi learned of Ubuntu when he was a young lawyer in South Africa and took it with him back to India, where it joined the principle of Ahimsa (nonviolence) to animate his work to free India from British rule. In turn Martin Luther King studied Gandhi’s ideas in college. A statue of Gandhi stands at the King Center in Atlanta and the King Center supported anti-apartheid efforts.

Mandela regarded nonviolence as a strategy, but for King it was a moral stance, according to Mason. “Unlike MLK, he was not in principle committed to nonviolence. You can’t ask people to march if the police are just going to shoot them down.”

In the early 1950s, Mandela and the ANC tried a campaign of defying unjust laws and accepting the consequences, but for that to work, “there has to be a minimal social contract,” said Mason.

Mandela realized that nonviolent civil disobedience was no longer practical after the Sharpeville Massacre.

People assembled around the country to burn their passes, a hated symbol of apartheid, and to go to jail. On March 21, 1960, in Sharpeville, police panicked and fired on the protesters, killing 69 people and wounding 180.

After that, Mandela no longer called for nonviolent disobedience. He kept the idea of armed resistance alive, mostly as a negotiating chip, according to Mason. He was sentenced to prison for a military action, and spent 27 years there.

“One of the things that happens in prison is that he ages. He becomes more patient and more farseeing. He takes a wider view,” said Mason.

When Nelson Mandela was a young man, he lived in a tiny house in the Soweto Township in Johannesburg, now a museum. While he worked to end apartheid, enemies firebombed it and shot at it. The scorch marks and bullet holes are still visible in its walls.

As modest as the house is, there is one touch of regal luxury: a leopard skin thrown over a bed. It symbolizes his royal lineage. His Madiba clan, of the Xhosa tribe, are traditional leaders. Mandela upheld his heritage when he led his nation away from apartheid and into reconciliation.