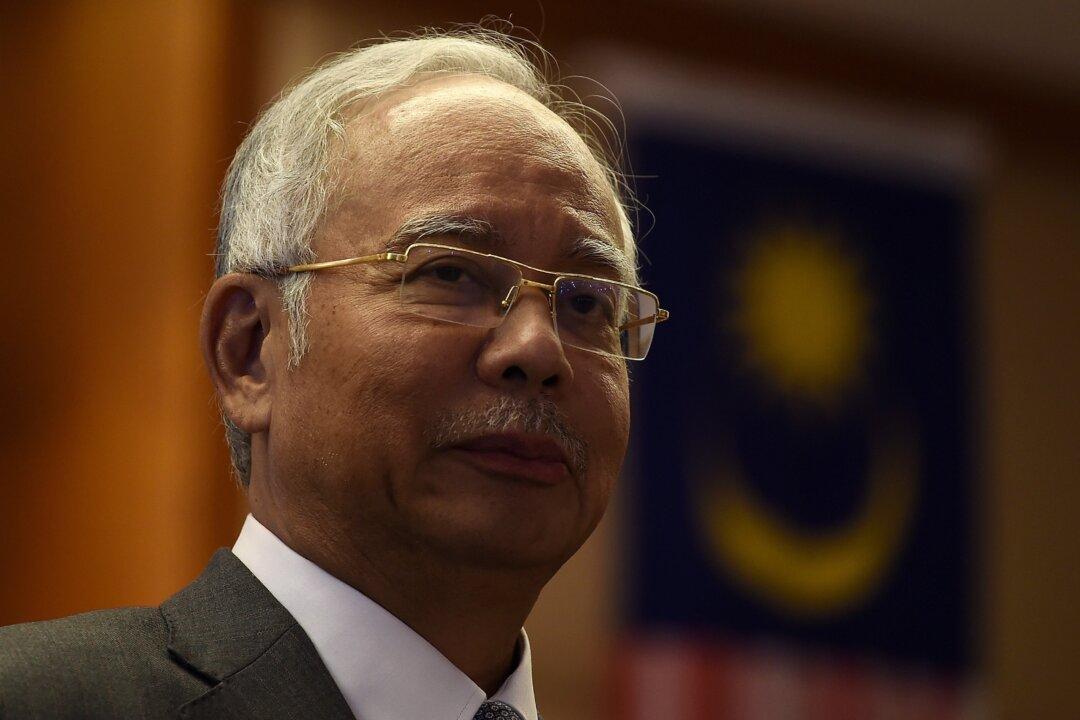

A serious political crisis is playing out in Malaysia, with no certainty as to when, or whether, it will be resolved. At the heart of this crisis is Prime Minister Najib Razak, who recently shut down an investigation into his financial affairs by the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC).

The investigation had been triggered by allegations in the Wall Street Journal that 2.6 billion Malaysian ringgit ($700 million) had been transferred to Najib’s personal accounts from companies linked to 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB). It is a state-owned strategic development company that is reportedly 42 billion ringgit ($11 billion) in debt.

Local news outlets The Edge Financial Daily, The Edge Weekly, and the Sarawak Report also published reports critical of Najib and 1MDB. Authorities quickly suspended or blocked these outlets and have issued an arrest warrant for Sarawak Report editor Clare Rewcastle Brown.