On Feb. 18, 2015, Epoch Times Hong Kong branch president Ms. Guo Jun gave a speech in Tokyo’s Shinjuku Keio Plaza hotel on the current affairs of China. She provided a detailed analysis of some key issues surrounding the great changes China is currently going through and their implications for Japanese and Hong Kong society.

(Part 1 and Part 2)

Before we move on, we need to talk about the characteristics of China’s political power structure.

Similar to other countries, China was an imperial autocracy society before entering modern society. The power structure of the imperial autocracy society is in a pyramid shape, with the emperor sitting on the top.

When the emperor passed away, the successor would usually be his son, often the firstborn son of the empress. As the power was passed down according to blood relationship, mother’s-side social status, and order of birth, the new emperor had a natural legitimacy of power.

The modern democratic society adopts a democratic voting system. Therefore the national chief executive’s power has natural legitimacy.

However, in the authoritarian communist countries, especially China, the power transfer is prone to having problems. The new power successor neither has a natural blood relationship nor is chosen by democratic election, but instead is the result of bargaining and balance of interests between coteries of insiders.

Therefore, this new supreme power controller does not have a natural legitimacy of power. His sense of crisis is much stronger than that of the new emperor of an ancient society or the leader of a modern democratic society.

Another problem is that any person with political ambitions would likely try a variety of techniques in order to obtain the highest authority at the top of the pyramid.

Power Struggle

This authoritarian regime is bound to create fierce power struggles. This is the result of the political structure of the autocracy.

Former Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader Deng Xiaoping designated Jiang Zemin as his successor, but after Jiang retired, his successor Hu Jintao did not have full control of the real power. Jiang’s faction arranged his allies into a number of key positions to prolong Jiang’s power. In an authoritarian regime, this control-behind-the-veil situation is very normal rather than an exception.

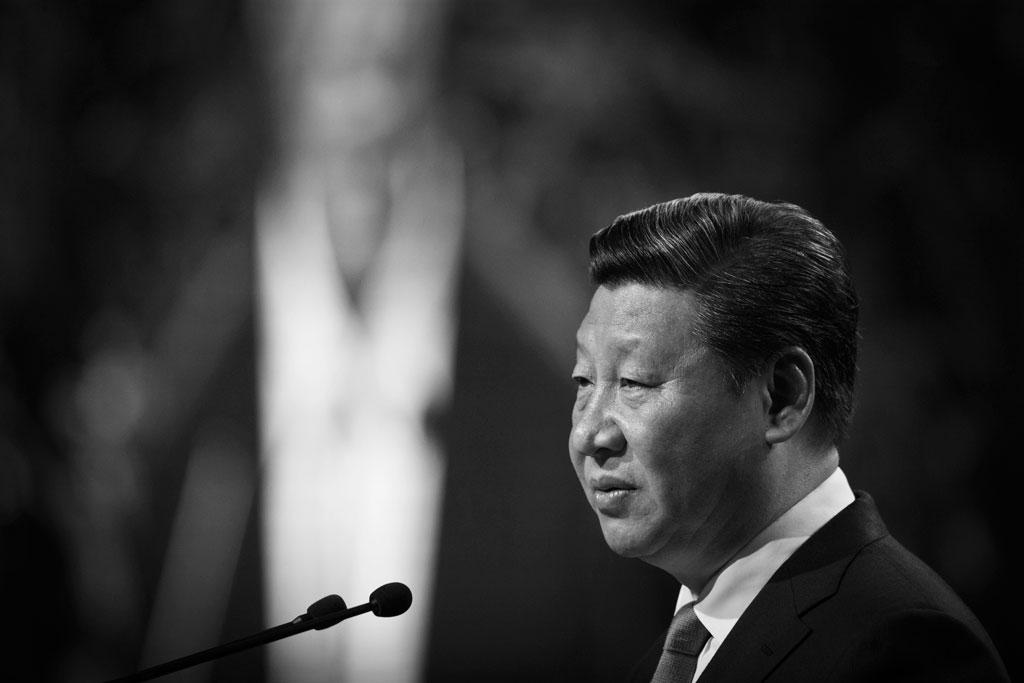

China’s current supreme leader Xi Jinping is the result of compromise among China’s core power circle.

Xi Jinping’s father Xi Zhongxun was one of the early leaders of the CCP. When Mao Zedong led the Red Army to northern Shanxi Province, Xi Zhongxun was the leader of the Red Army in northern Shanxi.

Because he accepted Mao’s Red Army, he was somewhat highly regarded by Mao. After Mao took power, though, Xi Zhongxun, and Mao’s relationship became estranged.

One of the reasons is that Xi Zhongxun was unwilling to slavishly follow some of Mao’s crazy policies. Xi Zhongxun might have been one of the few people who did not follow the political struggle tactics to purge others. Therefore he earned a good reputation among the CCP.

Xi Zhongxun was dismissed from his position in the early 1960s. At that time, China’s Cultural Revolution had not started yet. Xi Jinping fell from the red-noble class down to the bottom class.

When Xi Jinping was 15 years old, he was exiled to northern Shanxi to do farm work, following the policy of sending educated youth down to the countryside. Ten years later, he was able to return to Beijing to study at the university.

After graduating, Xi served two years in the army. Starting from Zhengding County of Hebei Province, within 20 years he moved up step by step from county governor to mayor and provincial governor.

Around 2007, when he was still Zhejiang’s provincial governor, he was appointed as the new leader of the CCP to replace General Secretary Hu Jintao. The decision was made by the core circles of power.

Once Xi Jinping became the successor to the highest authority, he became the focus of the CCP’s internal battle.

Jiang had retired for more than 10 years, but he still often intervened in high-level policies. Through his allies in the central office, Jiang was hoping to have a dominant influence when the CCP was to make decisions on the supreme power structure during the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (NCCP) in 2012.

However, Xi Jinping insisted on making all important decisions by himself and would not allow anyone to intervene. This led to the incident in which Xi suddenly disappeared from public view for two weeks in September 2012.

According to our inside information, Jiang insisted on inserting his selection of candidates as members of the Central Politburo and the Politburo Standing Committee. Xi Jinping responded with resignation.

After two weeks of “balancing,” Jiang had to give in to Xi’s demand, promising not to interfere with top-level matters. After Xi officially became the general secretary at the 18th NCCP, the first thing he did was issue a formal document to stop the old leaders from intervening in political and governmental affairs, including not issuing dedicatory statements in calligraphy and obtaining approval before publishing a memoir.

During this process, Jiang’s ally Zhou Yongkang imposed the biggest obstacle to Xi Jinping’s new policy. In fact, Zhou was opposed to the treatment of Bo Xilai, and he was also against Xi Jinping’s purge of the Political and Legal Affairs Committee.

Zhou and Bo’s relationship is well-known in China. They cooperated closely for years; one was responsible for inside matters, one for outside. With the assistance of other allies of Jiang in the Central Politburo and Politburo Standing Committee, they made Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao accomplish nothing during their 10 years of administration.

Bo-Zhou Coup

Hong Kong-based Phoenix Weekly’s Jan 13 issue reported the inside story of the political alliances between Zhou and Bo and details of their plotting a coup. The report said that Bo and Zhou had a closed-door talk in Chongqing, which involved negation of Deng Xiaoping’s reform theory. They sought to restore the Cultural Revolution, and they pledged to “have a big go at it.”

After Zhou returned to Beijing, he told his close followers: “If we want to do a great thing, we need to make use of people like Bo. He can help us to push ahead.”

This meant Bo could rush ahead to lead the CCP’s left side to the highest political power point. The report also said that even before the 18th NCCP, Zhou was no longer satisfied with the personnel deployment of local and high levels.

According to the retirement rules, a member of the Politburo Standing Committee shall not serve more than two terms and shall follow the “keep 7, remove 8” rule: if a member of the Politburo Standing Committee is 68 years old, he has to retire, and if a member of the Central Politburo is 67 years old, he can be promoted to the Standing Committee.

At that time Zhou was already 69 years old and had to retire, but he tried to form cliques in order to remain in power. He even attempted to get the position of Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress.

In fact, the real political patron behind Bo and Zhou is Jiang and his chief assistant, former Politburo Standing Committee member Zeng Qinghong. Why does Jiang want to support Zhou and Bo? The important reason is that he hoped to continue the policy of persecuting Falun Gong.

Xi’s Purge

After Xi Jinping came to power, he began a political purge in China using the technique of anti-corruption. In China this is called “striking flies and tigers at the same time,” which means raiding vigorously against all levels of corrupt officials.

Up to now, the preliminary estimate indicates that tens of thousands of officials have been dismissed and prosecuted, including about 50 provincial- and ministerial-level officials. Three are from the Central Politburo, former Central Politburo, and Politburo Standing Committee level: Zhou Yongkang, Bo Xilai, and Xu Caihou.

More than 30 army generals have been dismissed and prosecuted. The one with the highest position is Vice-Chairman of the Central Military Commission Xu Caihou. About three hundred military commanders of different levels have been changed.

In fact, the targets of Xi’s purge are Jiang’s allies. About 90 per cent of the sacked and investigated officials have obvious ties to the Jiang-faction.

That is why we have always maintained that China’s current political turmoil is in fact a power struggle between Xi and Jiang. The final outcome of this struggle is very likely to lead to Jiang Zemin, Zeng Qinghong and their main allies being purged.

On Jan. 11 this year, the Party mouthpiece Xinhua Net published a report on its home page titled “Xi Jinping: Anti-Corruption Has No Limit or Ceiling,” citing Xi’s comments on anti-corruption since the 18th NCCP. The report said that much of the content was being published for the first time.

The comment “no ceiling” was in Xi’s speech at the second meeting of the CCP’s Fourth Plenary Session on October 23, 2014. In the past 20 to 30 years, the most used anti-corruption comment has been: “No matter how high his position, will investigate him to the end.”

The word “ceiling” is obviously hinting that Zhou Yongkang is not the ceiling to the investigation.

On Jan 13, at the fifth plenary session of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), Xi Jinping said that Zhou Yongkang, Xu Caihou, Ling Jihua and Su Rong had “violated discipline and law.” He said that there was no restricted area for anti-corruption, but full coverage.

Xinhua Net highlighted Xi’s remarks, emphasizing that “corruption will continue in depth.”

On the same day, another headline on Xinhua Net’s home page said that Xi’s speech released six anti-corruption signals. Professor Wang Yukai of the CCP National School of Administration believes that Xi’s series of anti-corruption conclusions is a critical judgment.

In January 2015, Jiang’s eldest son Jiang Mianheng was removed from his position as president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Shanghai Branch.

Chinese official media published articles criticizing the monopoly and corruption in China’s telecommunications industry. Jiang Mianheng is China’s so-called telecommunications magnate; he controls China’s telecommunications industry.

This can be seen as a warning from Xi to Jiang and a signal that the tiger-purging action is approaching Jiang Mianheng and Jiang Zemin’s family, which is a true reflection of the current situation of the Xi-Jiang battle.

The future direction of China’s political trends will still surround Xi and Jiang’s power struggle.

(To be continued)

Translation by Susan Wang. Written in English by Sally Appert.