Wal-Mart could be the canary in the coalmine in forecasting a global trend downward in consumer spending. A few days ago the company announced it expects a reduced sales outlook for this year and falling profits for next. Likewise, Chinese private consumption as a share of the total economy has fallen steadily over the last decade from around 43 percent in 2004 to the current figure of around 36 percent.

Current consumption is not living up to expectations. This explains why global growth keeps falling, now running at 3 to 3.5 percent instead of the 4.5 percent rate of a decade ago. Behavioral trends, annoyingly persistent, vindicate this assertion, but are rarely brought to the forefront by economists mired in mainstream economics. They generally do not detect factors outside economics, and if they do, such trends are brushed aside as irrelevant.

In the 1930s John Maynard Keynes singled out consumption as the core of economics. Before Keynes, the classical school of economics maintained that the economy was controlled by production capacity, or the supply side. The Keynesian revolution turned to the capacity and willingness of people to consume, the demand side, as an explanation for the business cycle.

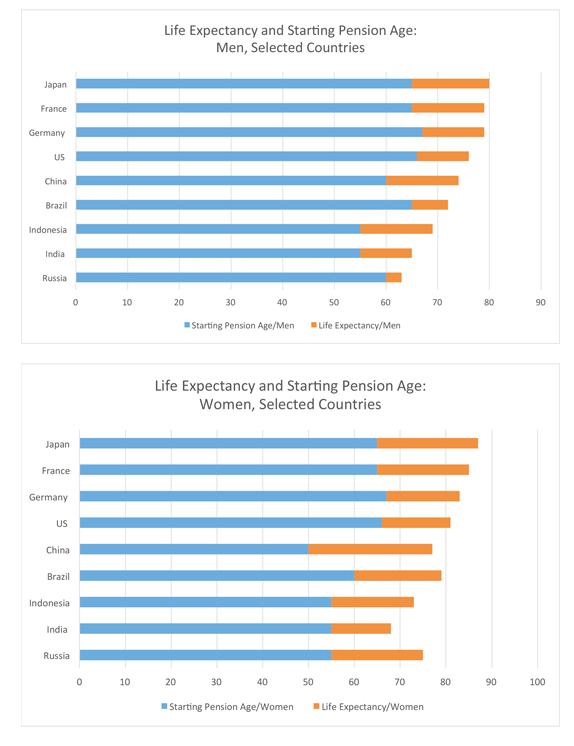

Demographics are a main culprit. Life expectancy was 60 for a British man and just over 40 worldwide when Keynes penned his thesis. Today, life expectancy for the global population is 71. The pension age, however, has hardly budged over the decades for most countries—standing near 60 to 65. Better health services offer more workers the prospect of fitness during retirement. Go back to Keynes’s era—when people preferred immediate consumption because they did not expect to have an active life lasting a decade or two after retirement. Acting rationally, they consumed before retirement and before they expected to pass away. If asked to postpone consumption and save instead, they wanted compensation in the form of interest.

Now it’s the other way round. People save to consume after retirement when they anticipate more leisure time and health expenses. Diminished expectations of future welfare benefits reinforce the hike in the savings rate. People fear poverty during old age. They register public finances under stress, mainly in Europe, concomitantly with inadequate private pension systems, mainly in the United States. The combined result is a higher savings rate and a lower propensity to consume.