The assassination of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln is an undisputed cornerstone of American history, but those who have studied the events suggest both the origin and ending of that seminal moment have ties to Canada. Some historians suspect the groundwork for a plot to kill the U.S. Civil War president was partially laid in a Canadian city that had become a haven for his political foes. When a simplified version of that plot succeeded 150 years ago in April 1865, they say it was a Canadian who ultimately led the effort that brought down Lincoln’s assassin. Historian John Boyko researched Canada’s direct contribution to the 19th-century conflict in his book “Blood and Daring: How Canada Fought the American Civil War and Forged a Nation.” He said John Wilkes Booth, the American stage actor whose fame shifted to infamy after killing the president, had long been conspiring to bring down the anti-slavery, union government. Boyko said his plans almost certainly came under discussion when Booth made a nine-day visit to Montreal in October 1864. “What Booth was trying to do was put together a team of people that could arrange the kidnapping, later the assassination, of Lincoln,” Boyko said in a telephone interview from Lakefield, Ont. “It was very difficult to do in Washington because there were so many spies for the government. But if you go to where other Confederate spies are, then you know that you don’t necessarily have to watch your back like you were in the United States, and that you were going to have the kind of...people that are going to back you in the enterprise. The best place to do that was Montreal.” History shows that American southerners opposed to Lincoln’s policies were able to find safe haven with their northern neighbour, which was officially not involved in the Civil War. University of Toronto professor Robert Bothwell said both Toronto and Montreal emerged as particular hubs of anti-union activity, adding that Confederate President Jefferson Davis eventually made Montreal his home in the years after his cause was defeated. Bothwell said Confederate sympathizers likely found pockets of strong support for their views in Canada, where British-born colonialists who shared their pro-slavery sentiments had also developed some anti-American feelings of their own. “They really wanted to see the end of the union and of the United States,” Bothwell said of the Canadian sympathizers. “Some of it is just strategic. If the United States were weakened, British North America plus the Confederacy would make for a very different kind of continent.” Boyko said Booth and several like-minded people gathered at Montreal’s St. Lawrence Hall, a hotel whose pro-southern leanings prompted it to advertise “the best mint juleps in the city.” Historical accounts suggest Booth spoke openly of his disdain for Lincoln during that trip. Documents also showed that he made withdrawals from a local bank during his stay, records of which were found on his body when he died. That death, Boyko said, was largely orchestrated by a Quebec-born soldier who was among tens of thousands of Canadians to enlist in the Union army. First Lt. Edward Doherty was tasked to lead the hunt for Booth, who had fled on horseback after shooting Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington D.C. The 26-man detail he assembled caught up with the fugitive 12 days after he fled and cornered him in a Virginia barn. According to a report filed later by Doherty, his orders were to bring the assassin in alive. Soldiers laid straw around the barn and set it alight in a bid to smoke Booth out, but Doherty’s account says a soldier was forced to shoot him when he showed signs of preparing to attack the surrounding troops. Doherty’s report describes the aftermath of that fatal shot: “Booth asked me by signs to raise his hands. I lifted them up and he gasped, ‘Useless, useless!’ We gave him brandy and water, but he could not swallow it. I sent to Port Royal for a physician, who could do nothing when he came, and at seven o'clock Booth breathed his last.” While one Canadian was leading efforts to apprehend Lincoln’s killer, Boyko contends another was masterminding an escape plan for one of his co-conspirators. John Surratt, the son of a woman who was ultimately hanged for her role in the assassination plot, was actively involved in the initial scheme to abduct the president. When that plan was scrapped and Booth had succeeded in his new efforts to kill Lincoln, Boyko said Surratt sought refuge in the city that Booth had haunted months before. “When the assassination happened he took off back to Montreal,” Boyko said. “It was a Montreal priest that hid him and eventually scurried him out of the country and over to Europe where he could escape justice.”

Lincoln Assassination Plot Had Canadian Link in Origin and Ending

The assassination of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln is an undisputed cornerstone of American history, but those who have studied the events suggest both the origin and ending of that seminal moment have ties to Canada.

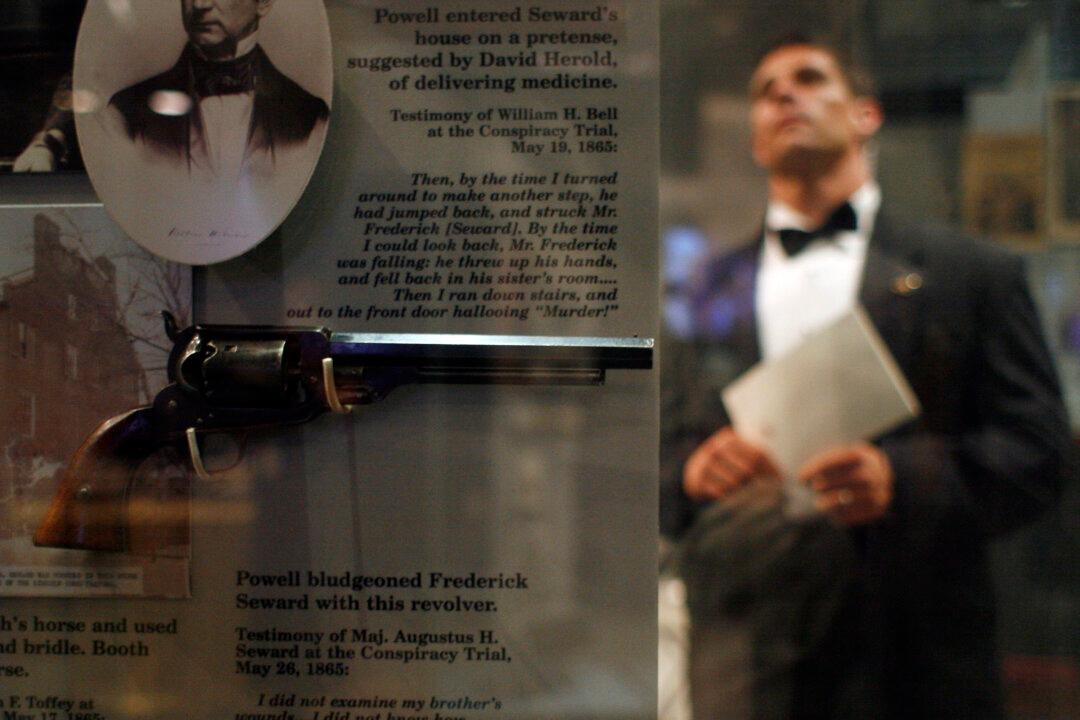

A Secret Service agent studies Lincoln's assassination exhibit in the basement of the Ford Theatre at the annual Ford's Theatre Gala in Washington. D.C., on June 24, 2007. Chris Maddaloni/Pool/Getty Images

|Updated: