This is the fourth in a series of articles by Epoch Times staff describing the foundations of Chinese civilization, and setting forth the traditional Chinese worldview. The series surveys the course of Chinese history, showing how key figures aided in the creation of China’s divinely-inspired culture. This installment introduces the Great Flood of ancient Chinese legend.

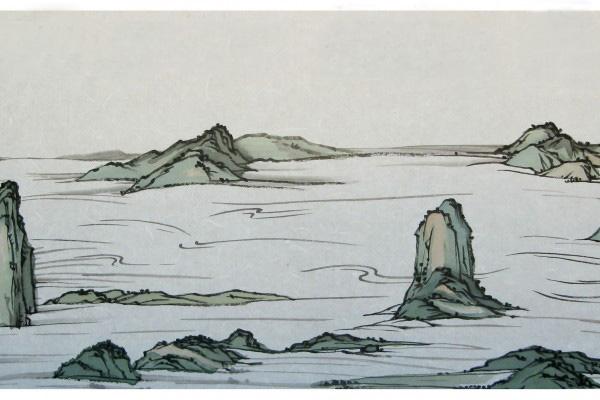

In the latter years of Emperor Yao’s reign, the world was deluged by violent storms and floodwater, as described in the mythological accounts of many cultures around the globe in addition to those of China.

The “Classic of Mountains and Seas,” a series of legendary accounts compiled during the Warring States Period about 2,500 years ago, describes the Great Flood as a tremendous onslaught by waves and rain.

A great western sea overwhelmed the mountains of western China and Inner Mongolia. The waters forced their way into the Yellow River and the Chinese heartland. Fields and dwellings were submerged and destroyed. Masses of people and livestock found their graves in the bellies of fish.

World Legends About the Great Flood

Descriptions of the Great Flood found in the various legends and myths around the world have many similarities. A common theme is that of the disaster being imposed upon humanity as divine punishment for moral degeneracy, and good and honest people comprising the surviving minority.

The damage done to civilizations around the world was huge. Western legends describe the annihilation of existing culture, while records in the Chinese “Book of Documents,” traditionally attributed to Confucius, consider the Flood to be the dividing line between history and prehistory.