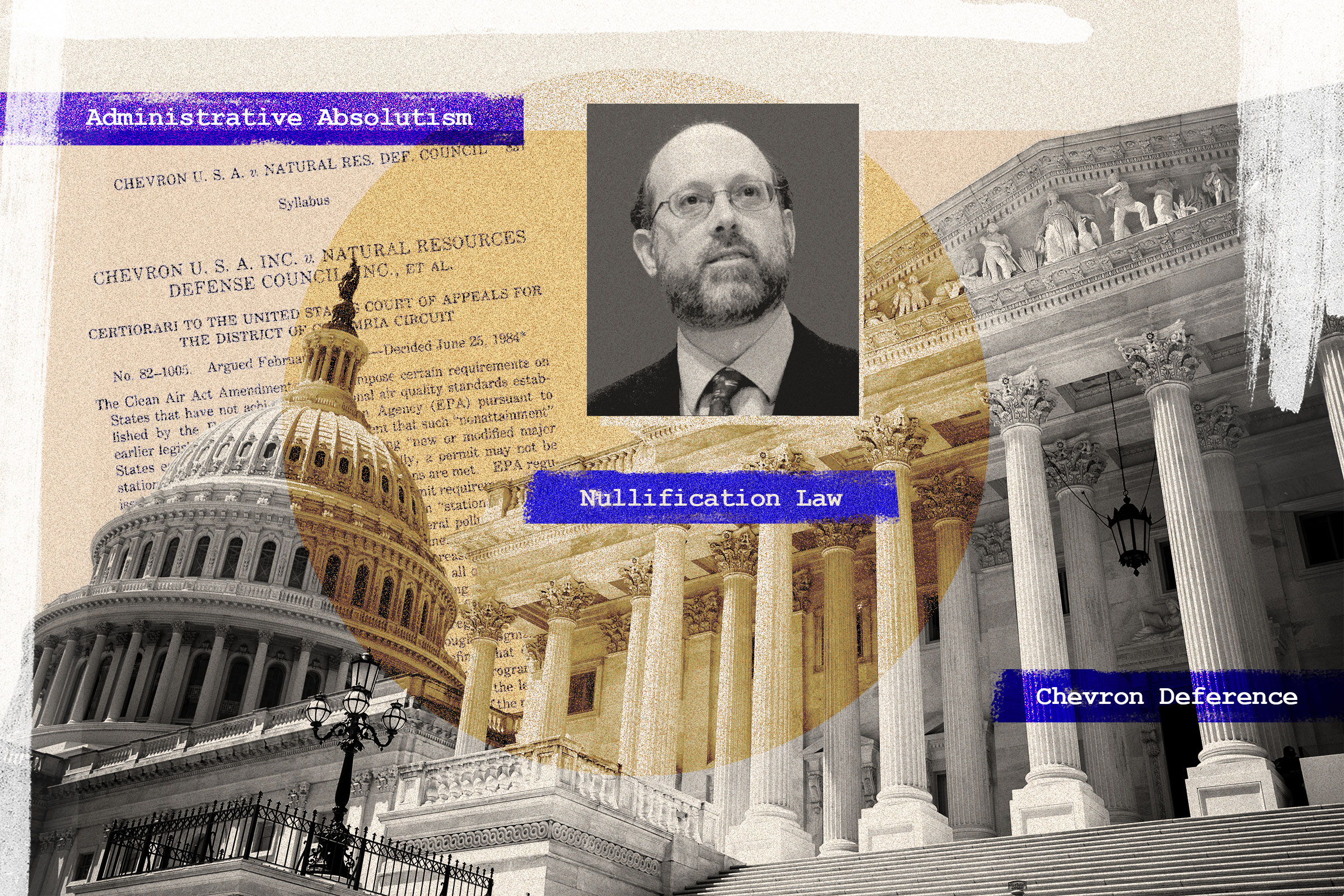

As the administrative state implements more regulations on Americans, a team of legal veterans has come together to fight the expansion of unelected government agency power.

Sometimes, they even win.

As the administrative state implements more regulations on Americans, a team of legal veterans has come together to fight the expansion of unelected government agency power.

Sometimes, they even win.