In Maui Fires, Defying Police Blockades Proved Life-Saving

Survivors of the Lahaina wildfire disaster in West Maui say defying police road blockades saved lives.

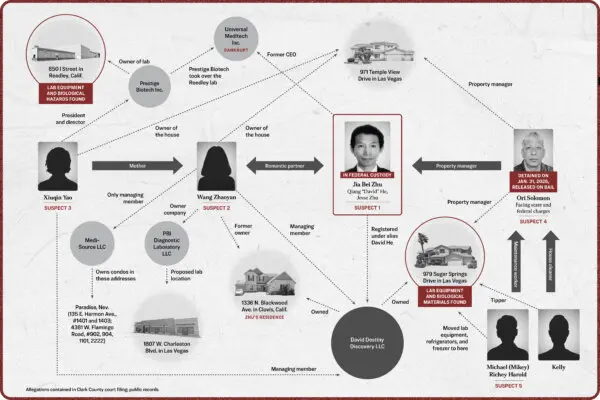

Illustration by The Epoch Times, Shutterstock

|

Updated:

Christy Albinson still has nightmares. The nightmares of children are the worst, she says, nearly a month after the tragic Lahaina wildfire in Hawaii.

“I’ve been traumatized. My dreams have been pretty whacko. They’re horrible—children buried in the sand. I’m spooked,” said Ms. Albinson said.