WASHINGTON—The Supreme Court has allowed Texas to use its strict voter ID law in the November election even after a federal judge said the law was the equivalent of a poll tax and threatened to deprive many blacks and Latinos of the right to vote this year.

Like earlier orders in North Carolina, Ohio and Wisconsin, the justices’ action before dawn on Saturday, two days before the start of early voting in Texas, appears to be based on their view that changing the rules so close to an election would be confusing.

Of the four states, only Wisconsin’s new rules were blocked, and in that case, absentee ballots already had been mailed without any notice about the need for identification.

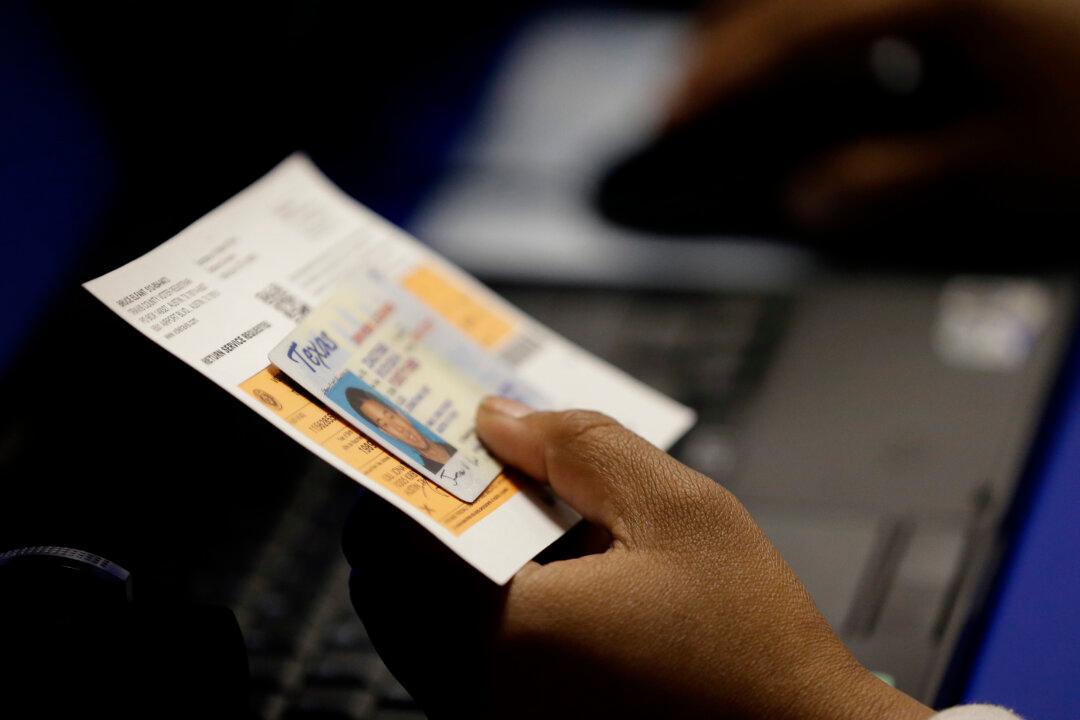

Texas has conducted several low-turnout elections under the new rules — seven forms of approved photo ID, including concealed handgun licenses, but not college student IDs. The law has not previously been used in congressional elections or a high-profile race for governor.

The Supreme Court’s brief unsigned order, like those in the other three states, offers no explanation for its action. In this case, the Justice Department and civil rights groups were asking that the state be prevented from requiring the photo ID in the Nov. 4 election, where roughly 600,000 voters, disproportionately black and Latino, lack acceptable forms of ID.

The challengers said that the last time the Supreme Court allowed a voting law to be used in a subsequent election after it had been found to be unconstitutional was in 1982. That case from Georgia involved an at-large election system that had been in existence since 1911.

Republican lawmakers in Texas and elsewhere say voter ID laws are needed to reduce voter fraud. Democrats contend that such cases are extremely rare and that voter ID measures are thinly veiled attempts to keep eligible voters, many of them minorities supportive of Democrats, away from the polls.

The details of the laws appear to be less important than the timing of court rulings.

In Wisconsin, half as many voters — 300,000 — did not have the required ID. Wisconsin also would accept photo ID from a four-year public college or a federally recognized American Indian tribe, while Texas does not.

In a sharply worded dissent for three justices in the Texas case, Ruth Bader Ginsburg said her colleagues in the majority were allowing misplaced concerns about chaos in the voting process trump “the potential magnitude of racially discriminatory voter disenfranchisement.” Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor joined the dissent.

Attorney General Eric Holder acknowledged the proximity to the election, but said that did not excuse the use of a law found unconstitutional by a federal judge. “It is a major step backward to let stand a law that a federal court, after a lengthy trial, has determined was designed to discriminate.”

Ginsburg leaned heavily on the findings contained in the 143-page opinion of U.S. District Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos, who called the law an “unconstitutional burden on the right to vote” and the equivalent of a poll tax.

Ramos, an appointee of President Barack Obama, blocked the law, but a panel of the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans said her ruling came too close to the start of voting.

Richard Hasen, an election law expert at the University of California at Irvine law school, has written extensively about the Supreme Court’s reluctance to allow potentially disruptive changes to take effect at the last minute.

“The idea that courts should not impose a new set of voting rules just before an election is not a new one,” Hasen said after the court earlier this month ordered a halt to the Wisconsin law.

That same motivation, though, appeared to be behind orders allowing restrictions on early voting, same-day registration and provisional ballots in Ohio and North Carolina to be in force for this election.

The partisan divide over the laws has been reflected on the court itself. Ginsburg and Sotomayor would have blocked the laws in all four states. Justices Samuel Alito, Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas would have allowed them to be used in each state.

None of the orders issued by the high court in recent weeks is a final ruling on the constitutionality of the laws. The orders are all about timing — whether the laws can be used in this year’s elections — while the justices defer consideration of their validity.

But civil rights groups are leery about the long-term prospects for challenges to these laws about voting access because of the Supreme Court’s track record in this area in recent years.

By a 5-4 vote in June 2013, the justices decided to remove from federal law the most effective tool for fighting voting discrimination. The court’s ruling in a case from Shelby County, Alabama, eliminated the Justice Department’s ability under the federal Voting Rights Act to identify and stop potentially discriminatory voting laws before they took effect.

That provision had prevented the voter ID law from taking effect in Texas. Indeed, only hours after the Supreme Court decision last year, Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott, the Republican who’s favored in the gubernatorial race, announced that the state would begin enforcing the new law.

From The Associated Press