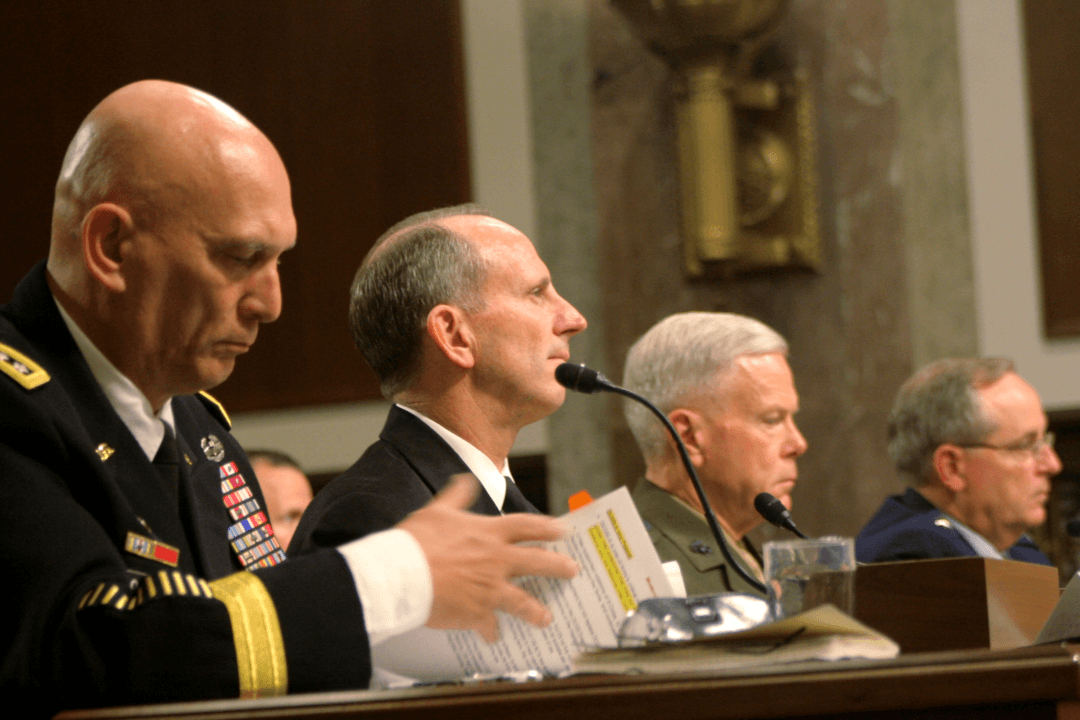

WASHINGTON—The Joint Chiefs of Staff warned the Senate Armed Services Committee on Nov. 7 of the harmful impacts of the sequester cuts that went into effect in March. The Budget Control Act passed in 2011 requires a $487 billion reduction in defense spending over the next 10 years.

Cuts will degrade the services’ readiness, modernization and reduce their capability to conduct major operations, according to the chiefs. While morale remains high for the soldiers, sailors, Marines, and airmen, morale on the civilian side has been hurt by furloughs and uncertainty.

“If sequestration continues, the services will have to cut active and reserve components end strength, reduce force structure, defer repair of equipment, delay or cancel modernization programs and allow training levels to seriously decline, reducing our ability to respond to global crises,” said Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.), chairman of the committee.

The ranking member on the committee, Sen. James Inhofe (R-Okla.), worried that if the sequestration is allowed to continue, our forces will be unable to support various operational plans around the world and may not be able to succeed “in even one major contingency operation.”

Chiefs Warn

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Army General Raymond Odierno, said the Army should have “the capability and the capacity to execute a sustained, successful major combat operation,” but said that if the discretionary cap reductions continue on schedule, it was his opinion, “it will make it very difficult for the Army to conduct one sustained major combat operation.”

In three years the active army’s “endstrength” has gone from a war time high of 570,000 to 490,000. Unless the law is changed, 420,000 will make up the active Army, which is below what it needs to ensure it can sustain a major combat operation, said Odierno. The Army National Guard and Army Reserve will also decline but proportionately much less.

Chief of Naval Operations, Adm. Jonathan Greenert, said that if the sequestration continued over the long term, 2013-2023, the Navy of 2020 would not be able to meet the requirement of the mission to “provide a stabilizing force,” with a fleet of 255-260 ships, which is about 30 less than today.

In his written statement, the admiral said that under the sequestration, the “Navy would not increase presence in the Asia-Pacific, which would stay at about 50 ships in 2020.” The Defense Strategic Guidance (DSG) plan, which was to have a fleet of approximately 295 ships in 2020 with 60 in the Asia-Pacific to achieve a re-balance toward the Pacific, will now fall way short.

The DSG is a crucial DoD strategy guidance document that lays out the blueprint for the future in terms of size and shape of the force to meet national security demands at acceptable risk. The chiefs are disturbed that with the continuation of the sequester and budget caps they will not be able to meet DSG requirements.

Chief of Staff of the Air Force, Mark A. Walsh III said, “The mechanism of the sequestration is a horrible business model.” No success businessman would do it this way, he said. It’s not that the services dispute the need for budget reductions in the next decade of $1.3 trillion. But “taking big chunks of money in the first years,” he said, is “what breaks us.”

Commandant of the Marine Corps, General James Amos, said that many multi-year contracts couldn’t be signed as a result of the sequestration. He said that they made a list of these “inefficiencies,” which are costing the Marine Corps $65 billion. For example, the corps has to buy planes one by one, so the cost is higher.

Walsh said that if the sequestration remains in place for fiscal year 2014, the Air Force could be cutting flying hours by 15 percent. “As a result, many of our flying units will be unable to fly at the rates required to maintain mission readiness for three to four months at a time.”

Smarter Ways to Save Money

Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) spoke of waste and inefficiency in the military.

He said the chiefs needed to do something about excessive costs of their staffs, which have grown “astronomically by the thousands.” He asked if anyone was fired for a $2 billion cost overrun on the aircraft carrier, Gerald R. Ford, or for cost overruns of the F-35.

Sen. Saxby Chambliss (R-Ga.) asked about expenditures that are mandated by Congress, but which the Department of Defense doesn’t want. At the top of the list is the M1 Abrams tanks. If production were suspended till 2017, the cost savings could be considerable, Chambliss said. Gen. Odierno agreed and said that the money could be better used. “We are producing more tanks we don’t need,” he said.

Sen. Chambliss questioned the value of DoD funding cancer research: $80 million a year on prostate cancer, $25 million a year on ovarian cancer, and $150 million a year on breast cancer. It’s not the proper place for the military to be involved in this research, which is better done by the National Institutes of Health, Chambliss said.

Morale

The cutbacks are bound to affect morale, according to the chiefs.

The Army furloughed 197,000 civilian employees, 48 percent of whom are veterans, and the air force furloughed 164,000 civilians, according to written statements provided by the speakers. In both the Army and Air Force, the civilians lost eight hours per week—a 20 percent pay cut for six weeks.

Gen. Odierno said the civilians, with the furloughs, shutdown, and reductions, “are questioning how stable is their work environment.”

For soldiers, “morale is good but tenuous,” he said. Recruiting and reenlistment has been steady, but “there is a lot of angst,” as he put it, with all the discussions about the future of the Army, possible reduction in benefits, not knowing whether they will have a job, etc. Yet despite their uncertain future, “they continue to do what we ask them,” which he found inspiring and personally frustrating.

Gen. Amos said that his civilians know that the sequester is going to require a cut in personnel. He said they are thinking, “Maybe I ought to look around [for another job],” something that worries him.

On the Marine side, Amos said the morale of a very young force—most between 18 and 22—is “pretty high.” They are not “garrison Marines” but actually like deploying. It will remain high so long “as we give them something to look forward to,” such as deploying to the Pacific, he said.

Boredom was also on Adm. Greenert’s mind regarding his naval aviators. He said that they may train for six or seven months, return to their base, and long to fly again. With the reduction in training dollars, there will be some aviators who have more flying hours than others on record. Greenert worries how these differences will affect retention.