Walt Disney is, to many people, the most influential person who has been in film. And after all, he garnered the most accolades, receiving as many as 59 Oscar nominations. But there’s another film titan that deserves a similar recognition: John Williams. In a career spanning almost six decades, he has been one of Western cinema’s most distinctive and indispensable musical voices.

Williams is the widely acclaimed composer of the scores for films such as Jaws, Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T. and, of course, Star Wars. In 2014 he received an Oscar nomination for his latest score to the World War II drama The Book Thief. This brought his track record to a whopping 49 nominations (and five Oscars won). But it isn’t just quantity: John Williams’s film work has been incomparably influential in terms of quality.

After rigorous classical training at the Juilliard School in New York and an extensive jazz practice, Williams began his film career in Hollywood in 1956 as a pianist in the Columbia Studio orchestra. You can hear him accompany Marilyn Monroe in Some Like It Hot and, more prominently, play the famous piano riff in Peter Gunn. In his apprentice period – a time when classical symphonic scoring was receding in favour of pop music and songs – he had the opportunity to witness the last days of the classical Hollywood music style and to learn the trade from the old masters.

Henry Mancini’s theme song ‘Moon River’ in Breakfast at Tiffany’s

In the mid-1960s – when Williams had come up through the ranks to become a composer – the leading figure was Henry Mancini, composer of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and the Pink Panther series. The predominant trend was to include appealing pop songs in scores written in a fashionable pop idiom. Studios needed to boost the ailing box-office revenues with incomes from the sales of tie-in LP albums.

Williams subtly challenged the musical norms of the time by employing, more extensively than others, such outmoded film-music techniques as the leitmotiv (each character comes with their own very recognisable theme which is reprised and varied throughout the score), Mickey-Mousing (visual actions are closely mirrored in the music), and the symphonic rather than the pop idiom. This can be seen (and heard) in such films as How to Steal a Million, A Guide to the Married Man, and Fitzwilly.

Old-fashioned symphonic scoring in Jaws

By the early 1970s, Williams was among the top practitioners in Hollywood, having won an Oscar for his musical arrangements of Fiddler on the Roof. But the breakthrough film was Jaws, the second output of his collaboration with Steven Spielberg, arguably the most symbiotic and enduringly successful relationship between a director and a composer.

For Jaws, Williams penned a fully symphonic score with echoes of Bernard Herrmann, Erich Wolfgang Korngold and other masters of Hollywood’s Golden Age. More importantly, the film featured no songs at all, something decidedly against the tide at the time. The daring choice was awarded an Oscar.

Finally, in 1977, Williams conducted the 86-man strong London Symphony Orchestra in his 800-page old-fashioned score for Star Wars. The symphonic sound of Hollywood’s Golden Age was back. Williams proved that a full symphonic score could still have much to say in contemporary cinema, not only as an immensely powerful narrative tool in the film, but also as a very successful commodity in the record market – the Star Wars LP sold more than 4m copies.

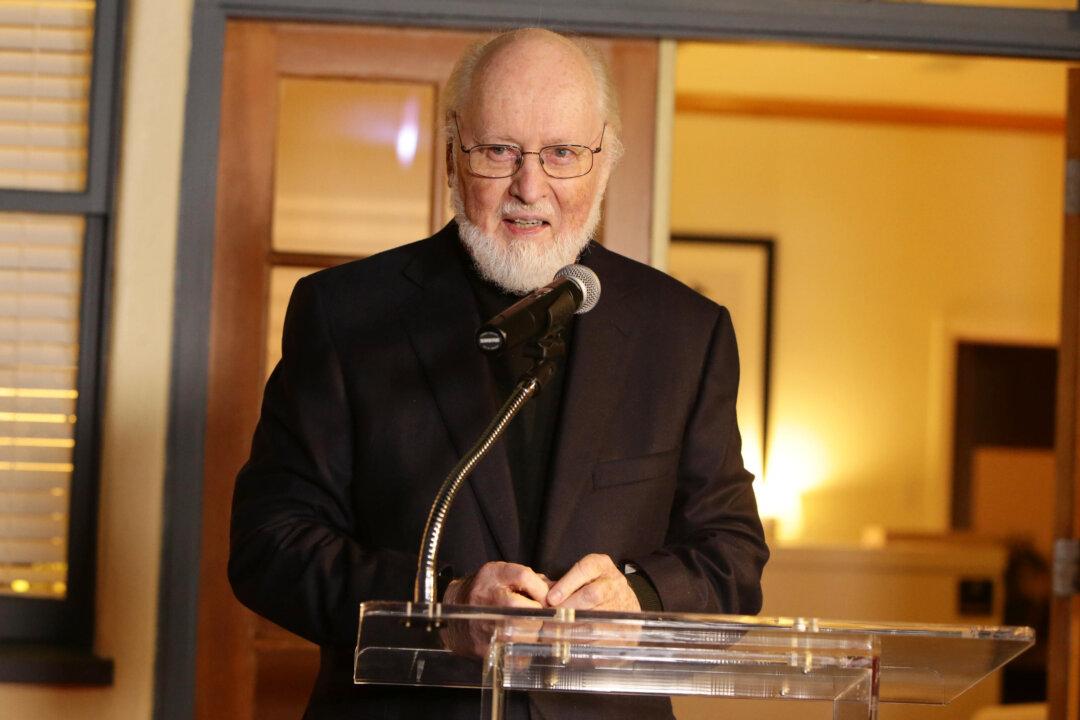

After 1977, Williams consolidated his neoclassical revolution in such films as Superman, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and the other instalments of the Star Wars and Indiana Jones series. Then in 1980 he accepted the prestigious conductorship of the world famous Boston Pops Orchestra where he was to stay at the helm for 15 seasons. As a conductor, Williams has done more than anyone else to promote the best of the film-music repertoire on the concert stage.

John Williams conducts the Boston Pops Orchestra in a multimedia suite from the Star Wars classic trilogy.

Back to statistics. Williams is the second most-nominated person in history. His most recent 49th nomination brought him a step closer to Walt Disney. Put into perspective, this is even more impressive. Disney was the head of a studio and therefore received nominations for each of the projects that he produced, even if he was not directly involved in artistic terms. Williams has received 49 nominations for works he has personally created.

The 82 year-old maestro is not resting on his laurels: he has signed to score the forthcoming seventh chapter of the Star Wars saga (due in December 2015). A new Spielberg project is on the horizon, new concert pieces (a Scherzo for Piano and Orchestra has been recently premièred by Lang Lang), and a dense concert schedule. His life in music is best summed up in his own words: “The more you work in music, the more years you spend with it, the more in love with it you become.”

![]()

Emilio Audissino does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.