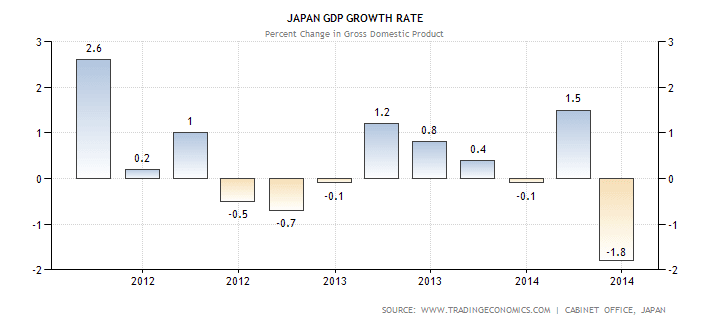

Sometimes economics can be easy. Plus 1.5 of growth in the first quarter and minus 1.8 percent in the second quarter comes down to roughly –0.3 percent in total.

This is more or less how much Japan’s economy contracted over the last two quarters, smoothing out a rise in sales taxes, which boosted consumption in the first quarter and decimated it in the second.

However, if it was just because of the taxes, the effect should have been neutral. But taxes are just one variable and the trend of growth is down, pretty much since Shinzo Abe took office in late 2012 and launched his infamous Abenomics policy. Using a mixture of statist and Keynesian policies, he wanted to spend money, print money, and raise taxes to spur growth and inflation.

The results have been rather sobering. The economy grew 1.2 in the first quarter of 2013 compared to the last quarter of 2012. The growth slowed to 0.8 percent, 0.4 percent, -0.1 percent, and now -0.3 percent for the last two quarters.

Launching several stimulus programs, the country ran a deficit of 8.4 percent of GDP last year, adding to a public debt mountain that now totals 243 percent. This is why Abe had to jack up the sales tax from 5 to 8 percent, with disastrous effects.

Now

However, the Japanese stock market almost doubled since Abe took office and the currency plunged by 30 percent. However, contrary to Abe’s expectation, this didn’t translate into economic growth, not even into more exports. Japan’s current account balance reached its lowest on record in May before rebounding to a small surplus in July.

Printing money reduces the value of the currency and mathematically increases the domestic price level. Equities go up, but so does the price for imports. Since Japan doesn’t have many resources, higher costs for raw materials squeeze company margins and leave the consumer with less money to spend on discretionary items.

Companies invest less in research and hire fewer workers, exacerbating the problem. In an economy like Japan’s, which provides a lot of value-added manufacturing, a strong currency would be more beneficial, as imports would be cheaper, but a high value-added product would naturally command a premium in world markets.

Don’t believe it? Take a look at Japan’s past.

Versus Then

After losing World War II, Japan allied itself with the United States and pegged the yen to the dollar at a rate of 360. The dollar was convertible to gold at $35 per ounce, so the currency was effectively under the gold standard within the Bretton Woods system. No money printing and monetizing of government debt was possible under this scenario. Nor was it ever needed.

Even after a brisk recovery in the 1950s, Japan’s economy kept on growing more than 20 percent every year in the 1960s. Instead of raising taxes, the government cut taxes every year starting in 1960 but still boosted tax revenue by a whopping 6 trillion yen in the process. Tax revenues made up 11.2 percent of GDP in 1960 and 10.6 percent in 1970, while GDP went through the roof.

Ironically, the Japanese government was bound by post-war legislation to balance its budget every single year. Since it had more money coming in, it needed to think of ways to get rid of it again. Unthinkable in today’s day and age.

Japanese consumers and companies saved and invested their newfound wealth to increase productivity and improve the quality of their products. Soon, they became export champions because of a strong currency policy—not in spite of it.

Japan would be well off if its leaders took an example in their country’s history instead of continuing reckless policies of currency devaluation.

Listen to Jeff Deist and Marc Abela discussing the Bank of Japan’s failed twenty-five year program of monetary stimulus, the resulting creation of hugely insolvent zombie banks, and the impossibility of “Abenomics”.

Source: mises.org