When Chen Guangcheng, the famous, blind Chinese rights activist, was in Linyi Prison in Shandong Province, a prison guard he was conversing with suddenly received a telephone call to his cellphone. Still standing in front of Chen, he answered the call—and then listened, saying not a word, for about three minutes.

“What kind of call is it that you just listen and don’t speak?” Chen recalls asking the guard after he hung up.

“I think it was a Falun Gong call,” the guard offered. “At the start they say this call will be three minutes and how many seconds. It was about the Communist Party and Tuidang.”

Tuidang—meaning “quit the Party” in Chinese—as of April 14 had attracted 200 million signatories. People from all walks of life across China receive telephone calls like the one that prison guard got, or get fliers slipped under their doors, or are persuaded through conversation, and later go on to renounce the Communist Party, or agree to have someone do so on their behalf.

An unknown portion of the mammoth number of Chinese who have quit their ties with the Party come from the bowels of the Party apparatus itself—due to phone calls like the one the prison guard received. Falun Gong volunteers overseas leverage these phone calls—targeted not just at the security personnel themselves, but also friends and family—to put persecutors under social pressure, have them stop committing violence against Falun Gong, and ultimately quit the Party.

One academic has called the phenomenon “interrupting Eichmann,” a reference to the famous Nazi bureaucrat whose later defense for crimes against humanity was that he was merely doing his job.

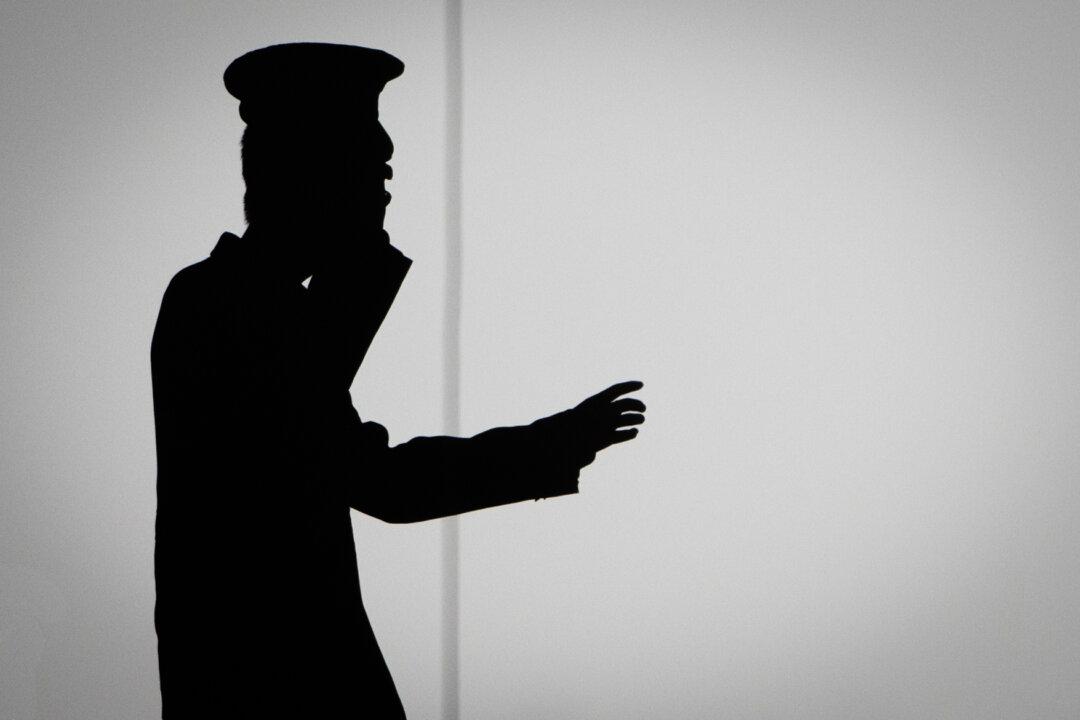

Daily Caller

Yan Fulan, a practitioner of the Falun Gong spiritual discipline and a Tuidang volunteer, is one of those that make the phone calls. From her small apartment in Flushing, she spends several hours in the morning—rising at 6 a.m. to begin calling, for the early evening in China—and several in the evening calling prison guards, labor camp directors, and agents of the 610 Office, the extralegal Party taskforce that was set up to oversee and coordinate the persecution against Falun Gong.

“We call those in the public security bureaus, the police lockups, and wherever their evil nests are,” Yan said in a recent interview. She and other callers are fed the numbers from volunteers, some of whom scrape them from Minghui, a Falun Gong website.

“In past years we‘d call them, and they’d abuse us and wouldn’t believe what we were saying to them. They'd say it’s all fake,” she said. They would be particularly resistant to the idea that military hospitals in China had engaged in the mass, organized live organ harvesting of Falun Gong practitioners, leading to tens of thousands of deaths.

But these misgivings have diminished somewhat in recent times, she said, particularly with some notable purges of Party members who were instrumental in leading the anti-Falun Gong security campaign, including Zhou Yongkang, the former security chief, and Li Dongsheng, former head of the 610 Office.

“We‘d play them the evidence over the phone, five or six minutes. They’d listen to it all and have no argument. They say ‘I get it, I get it.’ We then give them a phone number for whistleblowers [so that they can report on crimes committed persecuting Falun Gong].”

Yan said that about 70 percent of the time a call goes through, the recipient is willing to listen, though other volunteers report a success rate of only one in 5 or 10.

'Evil Has Consequences’

One of the key messages that volunteers seek to impart to the guards is the concept of karmic retribution, an idea embedded in Falun Gong’s spiritual teachings.

A volunteer who calls herself Yinan, who has settled in New Jersey as a political asylum seeker from China, estimates that she has persuaded several tens of thousands of Chinese people to renounce the Communist Party. An unknown portion of these are Party officials and members of the security forces.

“Everyone knows that the evil Party is bad,” Yinan declares. Even to the extent that this idea is true, Yinan has found that it can sometimes be difficult to impart to people whose living is made from the Party. “We tell them that good and evil have consequences,” she said. She goes on to talk about how Falun Gong has spread through the world, and that only the Chinese Communist Party persecutes it. Sometimes those calls end with a resignation from the Party—other times, silence, or abuse.

Andrew Junker, a professor at the University of Chicago, presented a paper at a recent Asian studies conference looking specifically at the question of Falun Gong volunteers reaching members of the security apparatus and urging them to stop participating in the persecution of the discipline.

He called his presentation “Interrupting Eichmann: Falun Gong’s Transnational Boomerang,” and said that Falun Gong’s “telephone activism” is “an attempt to interrupt the street level experience of everyday sovereignty of bureaucrats and targets of the calls.”

“They‘ll call the brother-in-law or wife of a police chief,” Junker said in his presentation. “Imagine that phone call from Taiwan: ’Do you know your brother-in-law is involved in tada tada tada?'”

Yinan, the Tuidang volunteer, said that they often get their phone numbers from imprisoned Falun Gong practitioners in China, who memorize them based on photographs and numbers on the wall posters in jails and police lockups. Some of the information is also available online.

The overall effect of these efforts are difficult to quantify, since it is unknown what portion of the 200 million renunciations from the Party now recorded come from the security forces or inside the Party—yet Chen Guangcheng said that the efforts are making real headway.

Chen recalls telling staff members at a re-education center of his encounter with the policeman that received the Tuidang phone call and his wary relationship with the Communist Party. “The cadres told me that this mistrust in the Party is deep and common. The whole apparatus of the Party and the security forces feel that the Communist Party’s days are numbered. Change will come, but no one knows when.”

Chen added: “The people I had contact with just serve the Party for a little benefit, or corruption. It was clear they were waiting for a collapse, and so as soon as the Party goes down, they'll be ready to flee.”