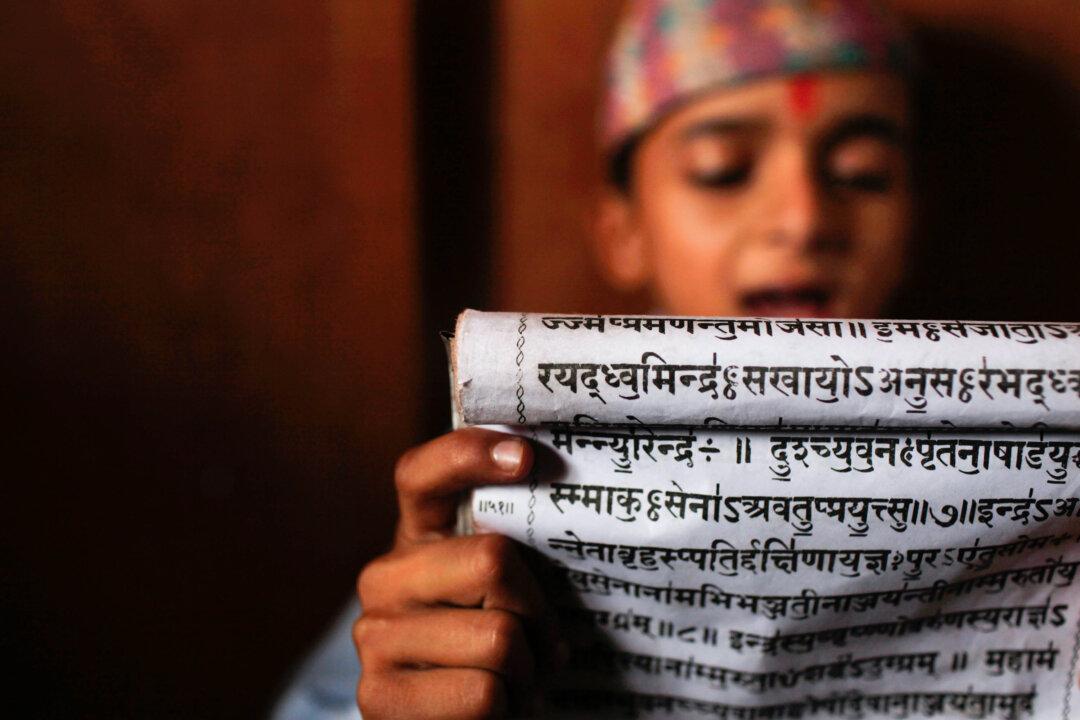

The new Indian government has engaged the country in a controversial revival of a relatively obscure ancient language. So far, it has required students to replace the study of German with Sanskrit in about 500 public schools.

In 2014, the Indian Ministry of Human Resource Development declared that the teaching of German in Kendriya Vidyalaya schools was contradictory to the country’s “three language policy,” which requires students to study English, Hindi, and one regional or classical language. The ministry said that foreign languages could only be taught as optional languages in state-run schools.

Efforts to popularize Sanskrit have won praise and support from language scholars. However, the government is coming under fire from those who believe the state-sponsored lessons are part of a larger attempt to impose Hindu culture on the nation.