The central government and the Kuki armed groups—the United Peoples’ Front (UPF) and the Kuki National Organization (KNO)—began their first round of political dialogue at Ashoka hotel in New Delhi on June 15.

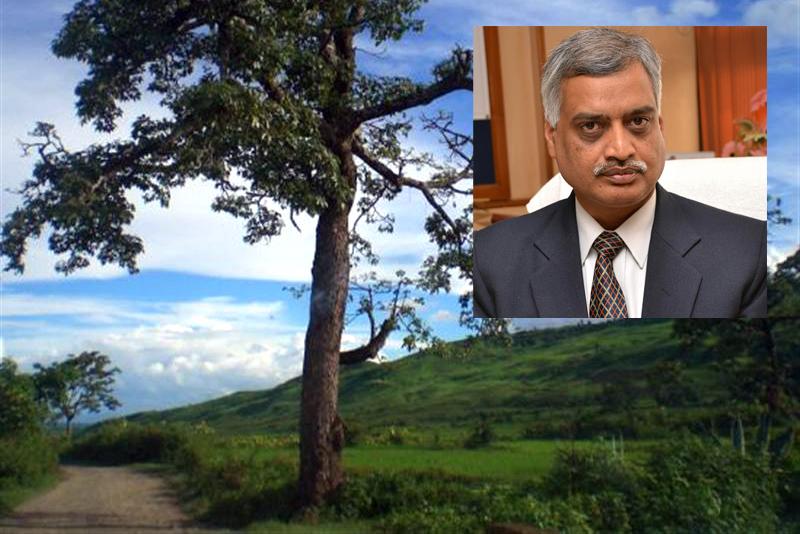

Satyendra Garg, joint secretary of the Ministry of Home Affairs, who led the central delegation, chaired the meeting, which was attended by representatives from the armed groups and the Manipur state government.

The issue of holding political dialogue has dragged on for years. The Indian Army and the Kuki armed groups have observed Suspension of Operation (SoO) since Aug. 1, 2005. A tripartite agreement, involving the UPF and KNO, the central government and the Manipur state government, was formally signed on Aug. 22, 2008.

The SoO was possible after the Kuki armed groups responded former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s call for resolving armed conflicts through dialogue. India’s Congress agreed, in principle, to initiate political dialogue within the framework of the Indian Constitution.