WASHINGTON—Whenever the People’s Republic of China agrees to discuss its human rights record with other governments, it does so in private. A hearing on Wednesday in Congress, with testimony by a human rights lawyer and the representatives of three groups victimized in China—Falun Gong practitioners, Uyghurs, and Tibetans, suggested the United States needs to go public with concerns about the Chinese regime’s record.

The hearing before the House Foreign Relations Committee was scheduled the day after the conclusion of the US.-China Human Rights Dialogue, an annual ritual in which State Department officials meet with their People’s Republic of China (PRC) counterparts behind closed doors.

The chair of the committee, Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FLA) made the worth of that dialogue a theme of the hearing, asking each witness, “What value is there in a so called human rights dialogue?”

Public Condemnation

Committee witness Mr. Li Hai, formerly a member of the Chinese Communist Party and a member of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, took part for several years in delegations representing the PRC in various unilateral and multilateral negotiations.

After the Communist Party began persecuting Falun Gong in 1999, Li was detained four times, with the longest detention being for seven years. He suffered torture and the hellish experience of “transformation”—the forced abandonment of his belief in Falun Gong and embrace of Communist Party doctrine.

In his prepared remarks, Li said, “if we truly want to free China, we need to free Falun Gong,” and called upon the United States to publicly condemn the persecution. Li said that public condemnation by the international community is what the CCP fears the most.

Li also asked Congress to “urge the Department of State to disclose any such information it obtained from Wang [Lijun].”

Wang Lijun gained notoriety when, after being relieved of his position as police chief of Chongqing, fled to the U.S. Consulate in Chengdu.

Before his time in Chongqing, Wang was a police chief in Liaoning Province and in a speech claimed to have personally witnessed thousands of organ harvesting operations there.

According to the investigators David Kilgour, David Matas, and Ethan Gutmann, an estimated 62,000 Falun Gong practitioners were killed by forced, live organ harvesting in the period 2000–2008, and the practice continues to be used to supply organs for transplantation in China.

In Chengdu, Wang is known to have been debriefed by U.S. officials and to have provided them with a stack of documents. Li suggested Wang may have provided information about organ harvesting.

When asked about the organ harvesting question after the forum, Rep. Smith said that “Organ harvesting is huge. It’s hard to get information from a closed society, but we know it’s happening, and I think we need to have a much more robust response to it.”

He added that “The Falun Gong have done great work in exposing this despicable, Nazi-like practice of taking people’s organs for transplant for somebody else and obviously killing the donor in most cases in the process.”

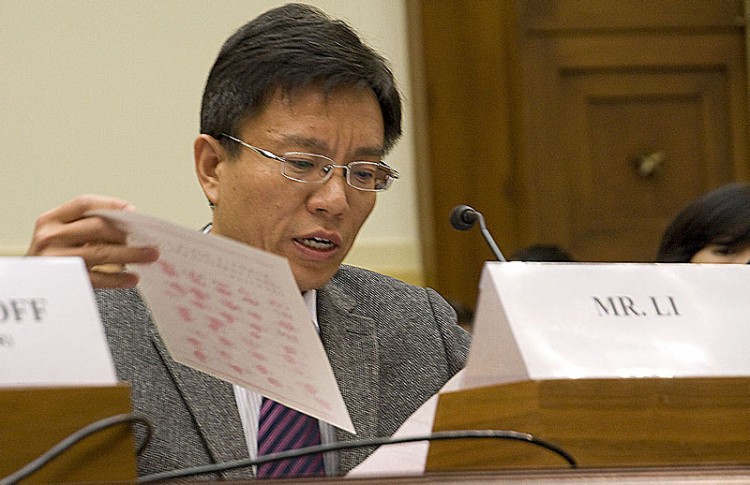

Li Hai testified that the persecution of Falun Gong is failing, with more and more people standing up against the CCP. At one point he held up as an example a copy of a document from China that had been signed with the thumbprints of individuals from Donganfeng Village in Hebei Province.

In that petition 700 villagers demanded that the CCP release their fellow villager, a Falun Gong practitioner named Li Lankui (no relation to Li Hai). They submitted this petition after spontaneously joining together and forming a human wall that prevented regime officials from detaining Li Lankui on June 1. On June 7, officials returned and abducted Li Lankui when no one was around.

Intensified Repression

Bhuchung K. Tsering of the International Campaign for Tibet spoke about how the self-immolators in Tibet have been protesting political, cultural, religious, and social injustices. Tsering also reported that the PRC authorities in responding to the self-immolations have, rather than address the Tibetans’s grievances, only tightened restrictions.

Tsering also pointed out how the Chinese regime’s soft power, in the form of Confucius Institutes, was endangering the ability to talk in the West about the injustices in Tibet.

The Chinese regime funds Confucius Institutes and Confucius Classrooms in schools around the world. The Institutes and Classrooms teach Chinese and Chinese culture, but, according to Tsering, come with strings attached.

Click www.ept.ms/ccp-crisis to read about the most recent developments in the ongoing crisis within the Chinese communist regime. In this special topic, we provide readers with the necessary context to understand the situation. Get the RSS feed. Get the new interactive Timeline of Events. Who are the Major Players? ![]()

“We have seen reported, and heard anecdotal evidence, that discussion on sensitive topics such as Tibet are discouraged if not prohibited,” Tsering said. “Further, the Institutes are used as dissemination platforms for Chinese propaganda on Tibet.”

Rebiya Kadeer, the well-known Uyghur democracy activist, told the committee that since July 2009, when protests took place in the capital of Xinjiang Province (which she identified as “East Turkestan”), Uyghurs have seen an intensification of human rights abuses.

She also explained how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had attempted to press her family in China into their service in their anti-Kadeer propaganda after she was marked an enemy of the state.

Ideas With ‘Teeth’

Committee members probed the thoughts of witnesses in a series of questions following the testimony. The general sense among participants was that the United States is not doing enough to push the CCP to stop its human rights violations, and is sticking mostly to ineffectual and timid statements in private rather than the aggressive public approach that might actually have an impact.

The human rights lawyer Jared Genser is the founder of Freedom Now, a group that advocates for the release of prisoners of conscience. He offered the committee several proposals.

He suggested the preparation of a public list, for example, of all Chinese Party officials involved in torture, wrongful imprisonment, disappearances, and other crimes against international law: their activities would be listed and made available to the public, a ban would be issued on their entry to the United States, and any U.S. assets they held would be frozen.

“Just by gathering evidence from existing cases we could come up with thousands of names. That would be the first batch.” Ideas like this may have an impact because they have “teeth,” Genser said.

U.S. public diplomacy could also be leveraged to helpful effect in educating the public about human rights abuses in China: inviting dissidents to the Oval Office to meet with President Obama, or having the President meet with Geng He, wife of Gao Zhisheng, the human rights lawyer that was disappeared and tortured after defending Falun Gong practitioners—he is currently in prison.

Genser agreed with the point made by Li Hai on the importance of publicly condemning the Chinese regime’s human rights abuses.

Genser said that the United States should have at least as much gusto in attempting to protect human rights as the Chinese regime shows in violating them. “They’re unapologetic and clear about what they do to their people to maintain power,” he said.

Attendees and committee members seemed supportive of this approach, but some were slightly skeptical that it would be adopted, given the current trajectory of the administration’s dealings with the Chinese Communist Party.

“Don’t hold your breath on that one,” Rep. Smith uttered more than once.

A precondition of rolling out policies like the above, which are radical from the perspective of current U.S. engagement with the regime, would be “a fundamental reassessment, what I would call a policy review, of U.S.-China policy,” Genser said in response to a question after the hearing.

“When you’ve tried a number of things and they don’t work, you have to reassess your tactics.”

The Epoch Times publishes in 35 countries and in 19 languages. Subscribe to our e-newsletter.