Every year when spring comes, the Chinese regime becomes nervous. That’s especially true this year, as the spring brings a number of “sensitive” days.

According to the Chinese Communist Party’s tradition, any memorable event should be marked with a big celebration every 10 years and a small celebration every 5 years. This started with the CCP’s National Day, but now it even applies to incidents that are bad memories for the regime.

This year happens to be the “small year” for several such events. Five years ago on July 5, there were mass riots among Uyghurs in Ürümqi, the capital of Xinjiang Province. Fifteen years ago, Falun Gong practitioners appealed in Beijing on April 25, which was followed three months later by the beginning of the persecution of the spiritual practice.

Twenty-five years ago on April 26, the momentum toward the Tiananmen Square Massacre seemed to become inevitable. Fifty-five years ago, on March 10, 1959, the Tibetan uprising began in Lhasa.

Each of these dates is an inflection point—afterward things took on a different value. Looking back after 5, 15, or 25 years, some people might say, if “x” hadn’t happened, things could have been different, and the Chinese people would be better off.

Maybe history doesn’t work that way. In some cases, there never was another option. Take as examples two sensitive days from last week, April 26 and April 25, which are each related to a turning point in history, respectively the Tiananmen Square massacre and the persecution of Falun Gong.

Only One Outcome

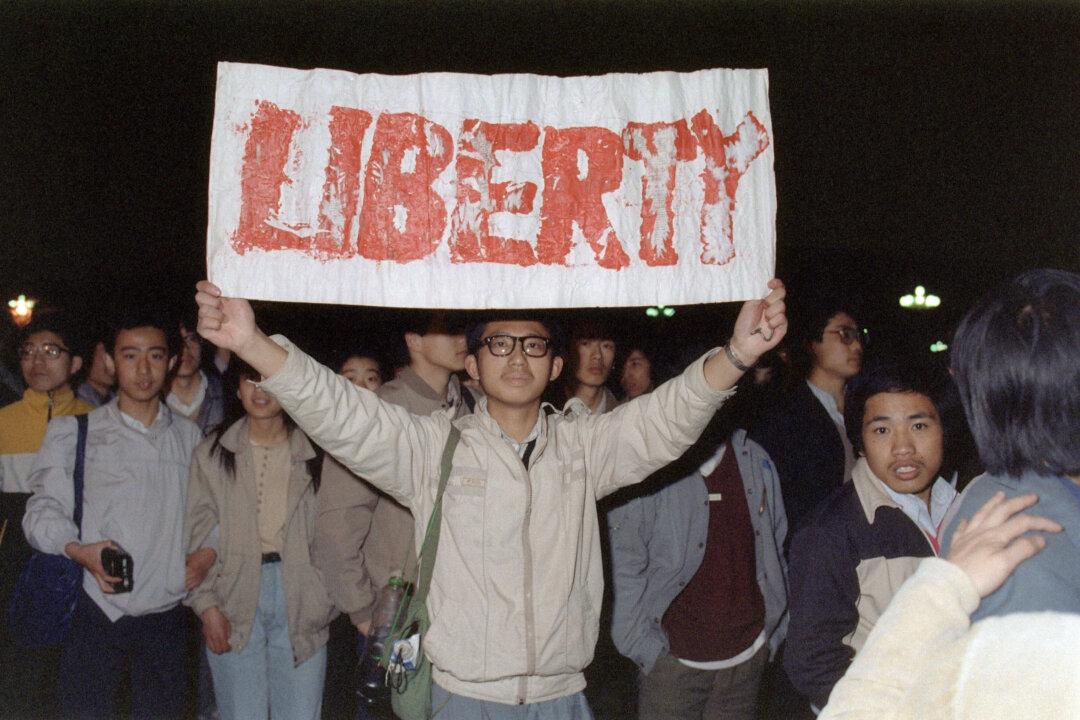

On April 26, 1989, the People’s Daily published the editorial “It Is Necessary to Take a Clear-Cut Stand Against Disturbances.” The reforming, former general secretary Hu Yaobang had died on April 15, and a week later, an estimated 200,000 students mourning his death had marched on Tiananmen Square.

At the moment the editorial came out, the students’ passion had already begun to burn itself out, and they were getting ready to return to school. The editorial defined the student gathering as a challenge to the Party’s authority, something that had never been tolerated. The students rejected that claim, demanded the editorial’s retraction, and dug in their heels.

The tone of the editorial reminded people of the Cultural Revolution, which had ended 13 years earlier. Its blunt threat signaled future political persecution and retaliation. A People’s Daily’s editorial at that time was considered the voice of the highest authority. During the Cultural Revolution, it was the voice of Mao himself.

Most people agree that the editorial was a turning point and that afterward a bloody crackdown was inevitable. Some people still say that if the People’s Daily hadn’t published that editorial, the Tiananmen Massacre wouldn’t have happened.

Did this “if” ever exist? No. During the 1989 student movement, from the beginning to the end, there was only one possibility available. The students must surrender unconditionally and wait for their punishment.

The CCP has never negotiated with anyone when it’s stronger than the opponents. During the civil war with the Nationalists in 1949, when the nationalist army in Beijing and the surrounding communist army both declared the “peaceful liberation of Beijing,” this declaration actually meant the unconditional surrender of the nationalist army.

In 1951, when the “Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet” was signed, no matter what was written in the agreement, the CCP considered it the complete surrender of the “Local Government of Tibet.”

In 1957, those who were later labeled as the Rightists believed Mao’s encouragement to make “positive suggestions” to the Party. But they forgot one thing, the CCP doesn’t listen, doesn’t negotiate, and doesn’t keep promises. Many “rightists” paid for their mistake with their lives.

The CCP only recognizes one rule—win or die. There is no win-win outcome. People still remember then-Premier Li Peng’s bad attitude when he met the student delegates in 1989. Actually, it would have been a surprise if he hadn’t behaved that way.

Thriving on Persecution

Ten years to the day after the People’s Daily editorial was published, on April 25, 1999, more than 10,000 Falun Gong practitioners converged on the Central Appeals Office in Beijing. Many years later, people still speculate that if the practitioners hadn’t gone to Beijing, the persecution of Falun Gong would never have happened.

In such an alternative future, the persecution might not have begun on the same day as it did begin, but it would have happened all the same.

In Tianjin, a city just up the road from Beijing, a youth magazine had printed an article that made slanderous charges against Falun Gong, written by a propagandist who had made similar charges on other occasions. That propagandist was related by marriage to a top figure in the regime who would later play a major role in the persecution. Attacking Falun Gong seems to have been the family business.

On April 22 and 23, practitioners gathered outside the office of the magazine and demanded a retraction, which the magazine seemed ready to offer. But police arrived and beat and arrested the protestors. The police told the protestors they needed to go to Beijing to resolve this issue, which led directly to the practitioners’ appeal on April 25.

Before the Tianjin incident happened, there were already many similar slanderous reports, articles in newspapers, and TV programs against Falun Gong. Falun Gong books had been banned since 1996. There were secret investigations of practice groups that laid the groundwork for future persecution. When practitioners gathered in parks to do Falun Gong’s meditative exercises together, they were often harassed, sometimes with water hoses or sound trucks.

There was always someone inside or outside the Party who was making trouble for Falun Gong practitioners. Some acted out of ideology, some out of fear, and some just hated anything that was not in the Party’s dictionary.

Numerous political campaigns during the CCP rule have created these individuals who thrive on persecuting other people. Of course, other societies have such individuals as well. In China, though, the Party culture makes these sociopaths like fish in water. And the CCP’s whole mechanism of suppression and propaganda is there to back them up.

The Worst-Guy Rule

There is another “if” about the April 25 incident. Zhu Rongji, then premier, met Falun Gong practitioners there and effectively solved the issue peacefully. He promised to release detained Falun Gong practitioners in Tianjin, which was the direct trigger of the Beijing appeal. When the practitioners in Tianjin were released, and their release confirmed, the Falun Gong practitioners left quietly.

If the CCP leadership, or its head Jiang Zemin, had supported and endorsed Zhu’s solution, the persecution that has lasted for 15 years could have been avoided.

But the persecution wasn’t avoided, and Zhu’s solution was revoked. This outcome has to do with the nature of the CCP as well as with the character of Jiang Zemin.

Falun Gong’s principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance are directly opposite to the CCP’s principle of class struggle. The CCP doesn’t allow religious beliefs and practices outside its control. It never negotiates with the Chinese people. The CCP considers dialogue as a sign of weakness and thus a threat to its rule.

At the time, Jiang Zemin was the only one in the CCP’s top body, the Standing Committee of the Politburo, who favored a campaign of persecution. If the head of the Party was not Jiang but someone else, could the persecution have been avoided?

Actually, the real question should be why the worst guy always sits in the decision-maker’s seat in the CCP. We all know that former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping picked Jiang as his successor because Jiang had wielded an iron fist in shutting down Shanghai’s World Economic Herald when it showed sympathy with the students in Tiananmen Square.

Other provincial leaders had waited to see which way the wind was blowing. As for hostility to democracy and freedom, nobody could compete with Jiang.

That’s one of the functions of the CCP’s political campaigns: Find the worst individuals as the potential future leaders.

Outsiders look at those the CCP considers to be its domestic enemies and assume that each of these represents a wrong turn by the Party. Falun Gong practitioners, Tibetans, Uyghurs, human rights activists, rights lawyers, and even the Tibetan monks who set fire to themselves—why does the Party need to make war on these groups? They have all grown up under communist rule. Continuing to create new enemies is in the CCP’s blood.

The CCP’s definition of “right” and “wrong” is the opposite of common sense and universal values. For the CCP, those wrong decisions and wrong turns are the “right” decisions and the “right” turns.