For Voltage Pictures, producers of the movie “Dallas Buyers Club,” extracting substantial fines from a large number of Australians who downloaded their movie illegally should have been relatively straightforward. They had used the model in other countries successfully, and Australia had politicians and a legal framework that supported the protection of intellectual property.

The problem was, not only did they not get what they wanted from the courts but the plan has backfired. ... Australians are [not only] still downloading ... but have also gotten much better at covering their tracks.

Why Did It Go Wrong for Voltage Pictures?

Finding the Internet addresses of the downloaders was relatively easy. Voltage used a German company Maverickeye to simply monitor people who were “torrenting” the movie “Dallas Buyers Club” during two months of 2014.

Armed with the Internet addresses, they then went to the Australian Federal Court to ask them to force a group of Internet Service Providers to hand over the real names and addresses of the people associated with those Internet addresses.

The Dallas Buyers Club LLC (DBC), representing Voltage Pictures, succeeded in persuading an Australian court to force a group of Internet Service Providers to hand over the identities of 4,726 customers.

But it was a pyrrhic victory for DBC. The judge, Justice Nye Perram, imposed conditions on the specific way in which DBC could approach these customers. In particular, DBC would be required to put up a AU$600,000 bond before receiving the customers names and addresses. DBC was also expected to have any letter they planned to send to these customers approved by the Federal Court.

Justice Perram was concerned that DBC would resort to “speculative invoicing,“ which DBC had been doing in other countries, threatening ruinous fines unless accused downloaders settled for some commonly unspecified amount.

Unfortunately for DBC, their attempts to get letters approved by the Federal Court met with rejection each time.

At one point, DBC tried to convince the Court to allow them to approach a small number of the downloaders in return for a reduction of the original AU$600,000 bond to just AU$60,000. This was rejected as well, in part because DBC still wanted to charge people who it deemed as having uploaded the film a “worldwide non-exclusive distribution agreement,” which could have been as much as tens of thousands of dollars.

Justice Perram was obviously eager to wrap the proceedings up and put a deadline of Feb. 11, 2016, on the case unless DBC decided to try a different approach.

In the Meantime, VPN Use Increased and Downloading Continues

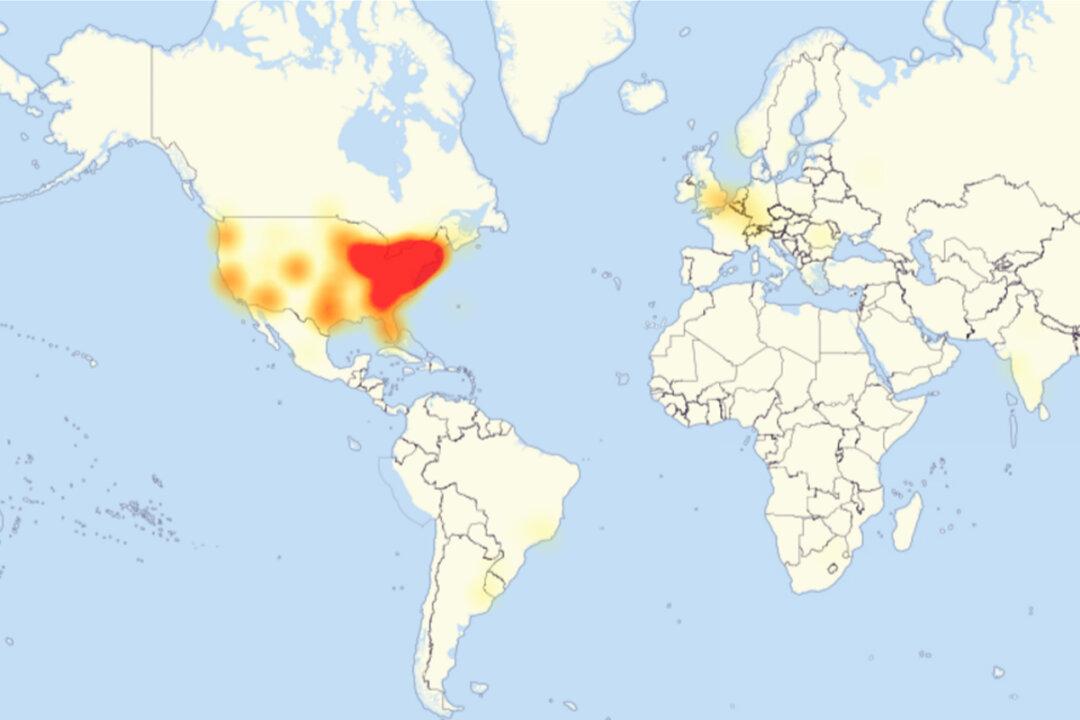

Meanwhile, of course, Australians turned to using Virtual Private Network (VPN) technology to cover their tracks when downloading and try and prevent any future DBC-like company coming after them.

VPN usage has also been driven by the launch of Netflix in Australia and the discovery by most users that U.S. content, enabled through the use of a VPN, was far more extensive than the current limited offering of Australian-licensed content. Although technically not something that should be allowed by Netflix, the use of a VPN to circumvent “geolocking” of content has so far been tolerated by them.

There has been an alleged drop in people reporting that they pirate content. Only 16 percent of those pirating less often claimed it was to do with a fear of getting caught. This was despite the fact that 51 percent of the people who admitted to pirating, knew about the case brought by DBC. 33 percent of people who are pirating less are doing so because they have access to content through services like Netflix.

The Moving Value of Movies

The irony of the entire story is that it is now possible to watch “Dallas Buyers Club“ on Netflix legally and essentially for free as part of a free trial account. It is unsurprising that people associate little consequence to downloading a movie when the only thing determining the value is the length of time from the movie’s release date. This makes DBC’s quest to make examples of downloaders as a deterrent to others become even more ineffective the more time passes.

Companies like Amazon and Netflix understand the dynamic of distributing content globally at an affordable price. As they increasingly become the producers of this content, companies like Voltage Pictures, and the geolocked distribution mechanisms they rely on to make money, will be forced to change their practices to compete. This is far more likely to happen before they have managed to change the public’s attitude to downloading content.

David Glance is director of the Centre for Software Practice at the University of Western Australia. This article was originally published on The Conversation. The Conversation.