China is in. The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) executive board confirmed on Nov. 30 it will include the Chinese yuan in its reserve currency basket.

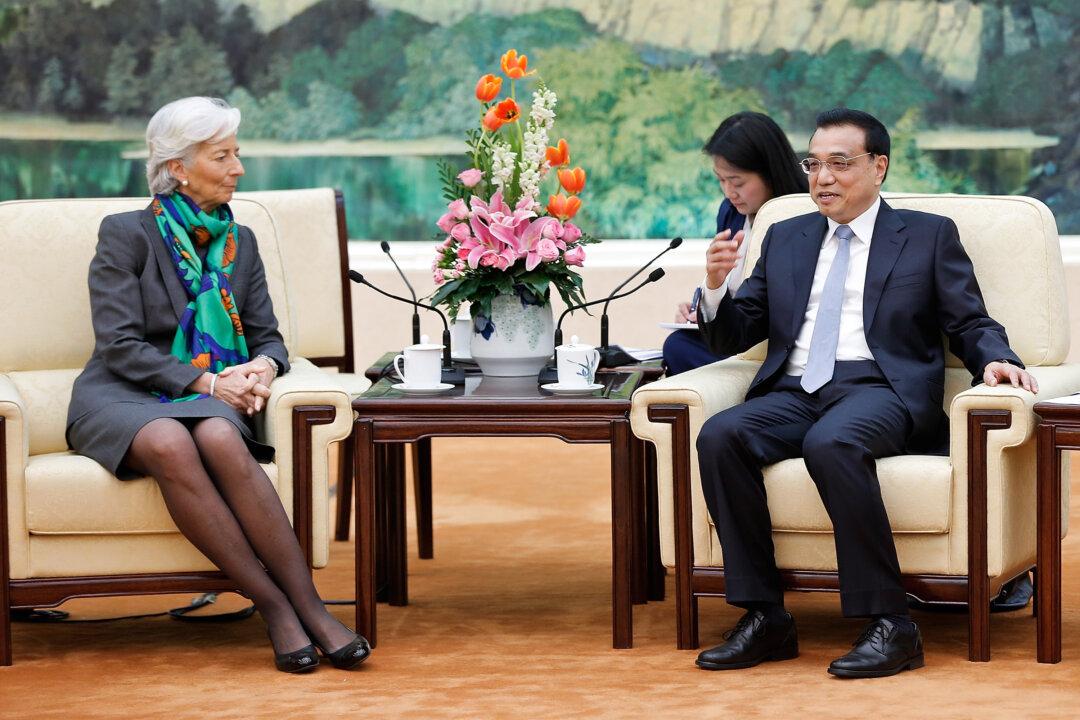

“The Executive Board’s decision to include the renminbi in the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket is an important milestone in the integration of the Chinese economy into the global financial system,” IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde said in a statement.

The decision by the executive board was a mere formality, after IMF staffers already said they supported the inclusion in a Nov. 13 report.

The SDR basket of currencies is the reserve currency of the IMF. Every IMF member gets an allotted share or can buy new rights, but the rights themselves do not have real monetary backing.

They can be exchanged against one or all of the currencies in the basket at the exchange rate the IMF determines. So far, only the U.S. dollar, the euro, the pound sterling, and the Japanese yen are part of the basket.

The Chinese yuan will be included as of Oct. 1, 2016. This is an exception to the policy, which is normally to add a new currency on Jan. 1, the year after the decision. The IMF reviews the composition of the SDR basket every five years.

“It is also a recognition of the progress that the Chinese authorities have made in the past years in reforming China’s monetary and financial systems,” stated Lagarde.

Extent of Chinese Reforms

In order to get in, China undertook some reforms in 2015 to make its currency more widely usable, as one of the conditions to be part of the basket.