Watching the dealings of the International Monetary Fund can be rather dull. On Jan. 22 for example, it issued a press release called “IMF Statement on Suriname.” Not terribly interesting unless you either work for the IMF or live in Suriname.

However, the IMF is an important international institution, and every once in a while it slips in a highlight that the general public then doesn’t notice, like on Jan. 27.

The press release with the poetic title “Historic Quota and Governance Reforms Become Effective,” for example, is one that’s worth some attention.

“The reforms represent a major step toward better reflecting in the institution’s governance structure, the increasing role of dynamic emerging market and developing countries,” it says in the statement.

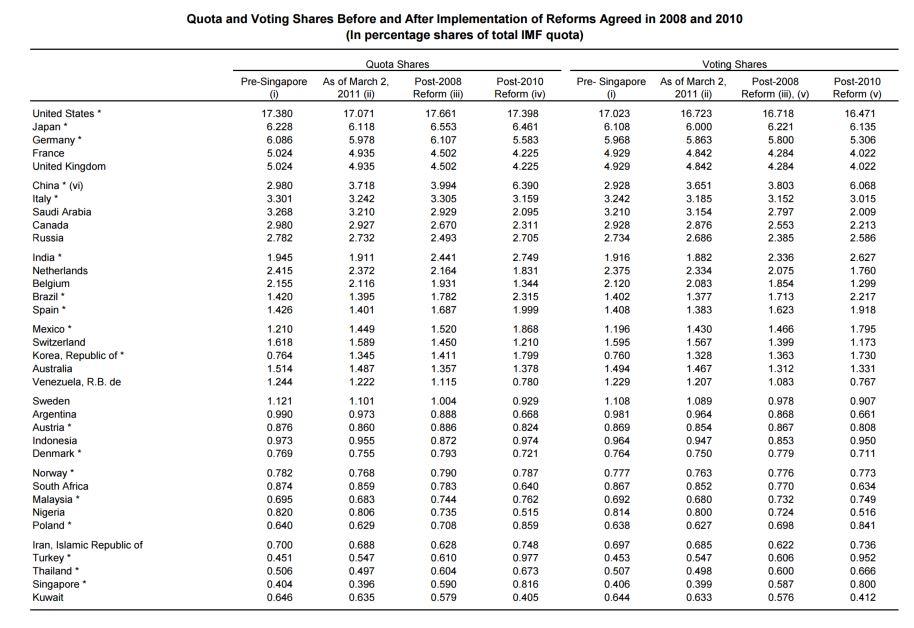

This means primarily more voting rights for the BRIC countries: China (6.07 percent), Russia (2.6 percent), Brazil (2.2 percent), and India (2.6 percent) are now top 10 members of the fund.

Their combined share is less than the U.S. share of 17.085 percent (giving it veto power); however, another interesting change makes BRIC’s increased voting rights very useful.

“For the first time, the IMF’s Board will consist entirely of elected Executive Directors, ending the category of appointed Executive Directors,” of the top five members consisting of the United States, Japan, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom.