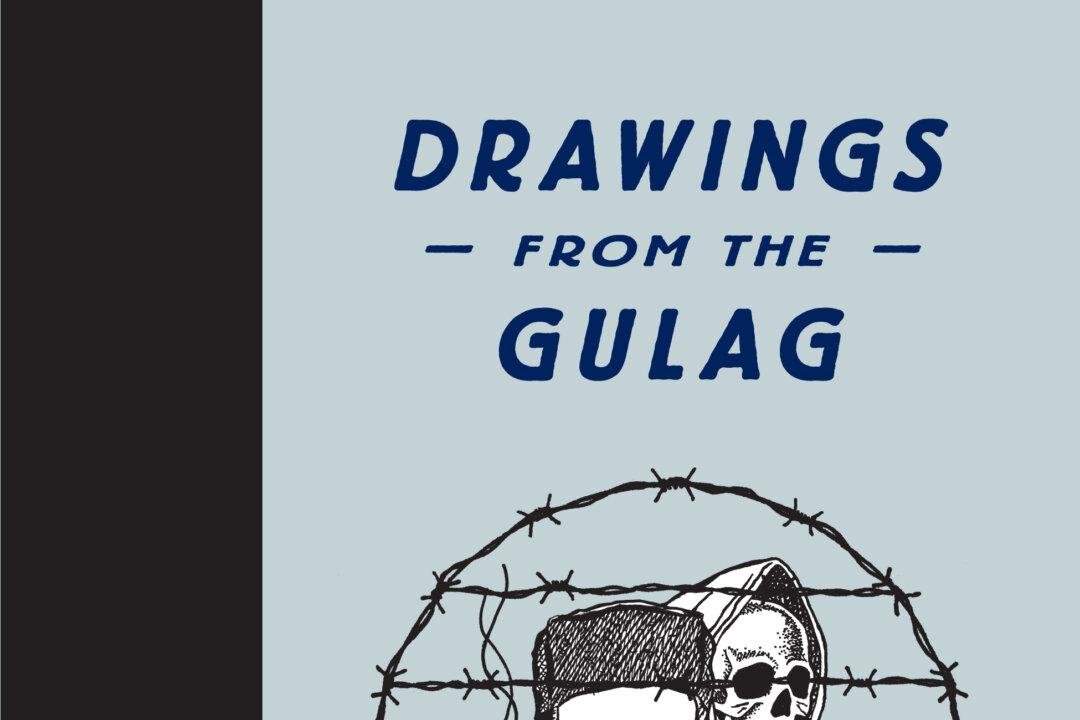

The horrors of the Soviet gulag system have been well-documented by steadfast survivors and discerning historians. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s “The Gulag Archipelago” (1973) recounted the prominent dissident’s experiences in the camps, while academic giants like Robert Conquest wrote works like “The Great Terror” (1968) at a time when many were ignorant or downplayed the scale and intensity of Soviet crimes against humanity.

Yet the atrocities—which impacted tens of millions of people—are removed from us by time and space. It’s been decades since the death of Joseph Stalin and the worst abuses of the Soviet system. Of the thousands of camps in the vast expanses of Siberia and the remote territories, only one has been preserved for public viewing.