“I happen to be with a few friends in Alberta learning more about the Canadian Tar Sands, and it’s impact on our climate, the way they affect the land, water and health of the indigenous communities that live here,” said DiCaprio, standing on the shores of Lake Athabasca in Canada’s boreal wilderness, where he working on a new environmental documentary in the midst of oil industry expansion.

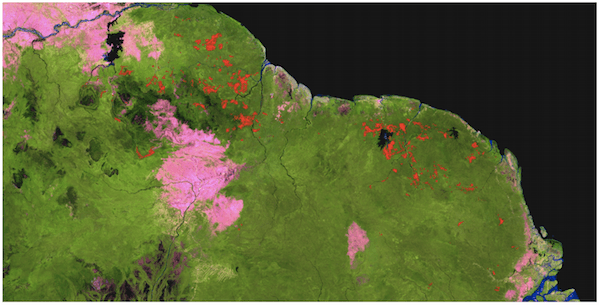

The massive tar sands operations in Canada’s boreal forests are large enough to be seen from the space shuttle. But way up in the northern forests, they are essentially hidden from public view – out of sight, out of mind. However, due to increased public awareness around environmental concerns and access to resources such as Global Forest Watch (GFW) satellite imagery, the invisible is being made visible and the public is able to gain a sense of the massive scope, scale and effects of oil sand extraction in boreal forests.

What are tar sands?

Large deposits of tar sands lie underneath 14,000 hectares (54,000 square miles) of boreal forest in the Alberta, Canada, an incredibly biodiverse region home to many species, as well as to first nations peoples such as the Cree. Tar sands (or oil sands, if you are in the industry) are a mixture of water, sand, clay and bitumen. That last component, bitumen, is what the oil industry seeks; it’s a thick, tar-like form of hydrocarbons that must be heavily processed before it can be used for energy. The methods of extraction and processing required to turn bitumen into fuel are energy intensive and cause a great deal of disturbance to the surrounding landscape.

There are two methods of Bitumen extraction: open-pit mining and in-situ drilling. In an open-pit mining operation, forests must be cleared completely. The land is excavated with heavy machinery – sometimes to a depth of 300 feet (91 meters) – and the sand is thinned out with water so that it can be moved to the plant where the bitumen is separated. In an in-situ drilling operation, multiple wells are drilled and steam is pumped underground to liquefy the bitumen for transport. In-situ operations are much less destructive to the landscape than open pit mining. According to the Canadian Association of Petroleum, 80 percent of tar sand reserves are potentially accessible through in-situ technology.

What is the issue?

Tar sands operations have been the subject of much controversy and debate over the past few years. Among the heated issues is the planned construction of the Keystone XL pipeline, which, if built, would be used to export oil from Alaska and Canada down to the Gulf Coast of the U.S.

Bitumen extraction itself is land, energy and water intensive. Extracting useful petroleum products from these deposits requires a huge amount of energy input and processing relative to other energy sources, including other oil sources. By some estimates, the return of investment (ROI) – the energy input for energy output – for bitumen is between 7:1 and 4:1. In other words, between 14 and 25 percent of the energy produced through tar sands is lost while processing it. For comparison, conventional oil drilling has an ROI of 25:1.

Another major issue with tar sand extraction and exploration is the amount of water required to separate the bitumen from the other components, and the pollution that results. Each cubic meter of bitumen extracted results in three to five cubic meters of leftover tailing water. This water, along with remaining sand, clay and bitumen, is stored in massive tailing ponds so the water can separate from the other components. These and other ponds containing wastewater that have come into contact with sulfur, heavy metals and byproduct molecules collectively called “asphaltenes” are stored to prevent groundwater and river contamination. However, concerns have been raised that these ponds are not adequately protecting water sources.

The solid waste produced by oil refining can also be difficult to store. Petroleum coke, also called petcoke, is a coal-like solid that is typically stored out in the open. Small petcoke particles pose serious health risks to the heart and lungs if inhaled. Chicago and Detroit have large, exposed, storage piles close to lower income neighborhoods. Citizens are encouraged to “call in” to report sightings of dust.

Impact on forests

Boreal forests – also called “taiga” – ring Earth’s high latitudes in huge swaths of primarily coniferous forests, dotted with wetlands. As a whole, they are among the planet’s largest carbon sinks, capturing and sequestering more CO2 from the atmosphere than do tropical rainforests. Canada’s portion comprises about a third of the world’s boreal forest, a largely continuous tract of that spans from coast to coast and is more than 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) wide, separating the tundra of the north from the deciduous woodlands of the south.

However, Canada’s boreal forests are disappearing, with logging outfits felling huge swaths, global warming heating up the habitats of species that evolved to live in the cold, and now tar sands operations displacing thousands of hectares of forest in the province of Alberta. According to Global Forest Watch, of Alberta’s approximately 39 million hectares of boreal forest, more than two million – or 5 percent – was lost between 2001 and 2013. As extraction ramps up to reach the estimated 170 billion barrels of recoverable bitumen underlying approximately 14 million hectares of forest, that number may increase significantly in the coming years.

Alberta oil production began in 1967, but only started expanding significantly in the 2000s when oil prices jumped. Between 2001 and 2013, 775,000 hectares of forest were lost in Canada’s tar sands region, according to Global Forest Watch, with some areas having lost more than half their forest cover. According to a 2009 report by GFW Canada, the amount of land that either already is or will be impacted by expansion of both in-situ and surface mining adds up to nearly 1,614,000 hectares. In other words, an area larger than Connecticut stands to be affected by tar sands extraction.

Down the line

As oil prices continue to rise, investors are throwing more and more money into tar sands expansion. However, a return on investment hinges on having a way to get the oil from production grounds to consumers. Enter the Keystone Pipeline.

Three phases of the pipeline construction have already been completed and are in operation. The first three run east from Alberta to Manitoba, then down to the Nebraska/Kansas border where a junction divides flow east to Illinois and south to the Gulf of Mexico. A fourth phase, the controversial Keystone XL Pipeline Project, is proposed as a bypass to the northern route, essentially connecting Alberta source directly to the U.S. Midwest.

The project is at the center of much debate, with tar sands operational expansion dependent on its approval while environmentalists and some members of Congress maintain it would lead to environmental damage. President Obama rejected the Keystone XL proposal in 2013 amid criticism that it would potentially harm Nebraska’s sensitive Sand Hills region. In April 2014, review of the project was extended indefinitely while a change in pipeline route is considered.

If the pipeline is approved, it may mean trouble for both the environment and investors.

“Oil sands are high-cost, high-carbon projects, being proposed at a time when both costs and emissions are under pressure to shrink; as such they should immediately hit an investor’s higher-risk screen,” said James Leaton, Research Director at Carbon Tracker. “Efforts to stay within a carbon budget, increase fuel efficiency, reduce costs and improve air quality mean that if capital continues to flow into oil sands, the projects risk becoming stranded assets.” http://www.carbontracker.org/site/kxl-press-release

Aside from its impacts on boreal forests, global warming, and on ecosystems near pipelines that could be affected by leaks, many at the tail end of the proposed Keystone pipeline in the U.S. Gulf Coast region also have concerns about bringing bitumen oil into their region.

“The Gulf Coast is already a dirty energy sacrifice zone,” Devin Martin, Associate Organizing Representative of the Sierra Club and native Gulf Coast resident told mongabay.com. “With our concentration of refineries, chemical plants, and pipeline networks, we already suffer from well blowouts, pipeline ruptures, plant explosions and continuous emissions of particulate matter and carcinogenic gases at much higher rates than other areas.

“The addition of tar sands bitumen, with its higher rate of petroleum coke waste, will only add more to this heavy environmental justice burden. Not to mention help to further destabilize our climate in one of the most vulnerable regions in the world for sea level rise.”

This article was written by Liz Kimbrough and Morgan Erickson-Davis, contributing writers for news.mongabay.com. For the original article and more information, please click HERE.