Whether an odor is pleasant or disgusting to an organism is not just a matter of taste. Often, an organism’s survival depends on its ability to make just such a discrimination, because odors can provide important information about food sources, oviposition sites or suitable mates. However, odor sources can also be signs of lethal hazards.

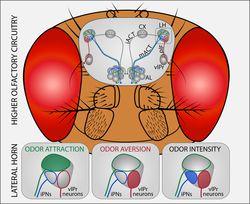

Scientists from the BMBF Research Group Olfactory Coding at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena, Germany, have now found that in fruit flies, the quality and intensity of odors can be mapped in the so-called lateral horn. They have created a spatial map of this part of the olfactory processing system in the fly brain and showed that the lateral horn can be segregated into three activity domains, each of which represents an odor category. The categories are good versus bad, as well as weak versus strong smells. These categorizations have a direct impact on the behavior of the flies, suggesting that the function of the lateral horn is similar to that of the amygdala in the brains of vertebrates. The amygdala plays a crucial role in the evaluation of sensory impressions and dangers and the lateral horn may also.