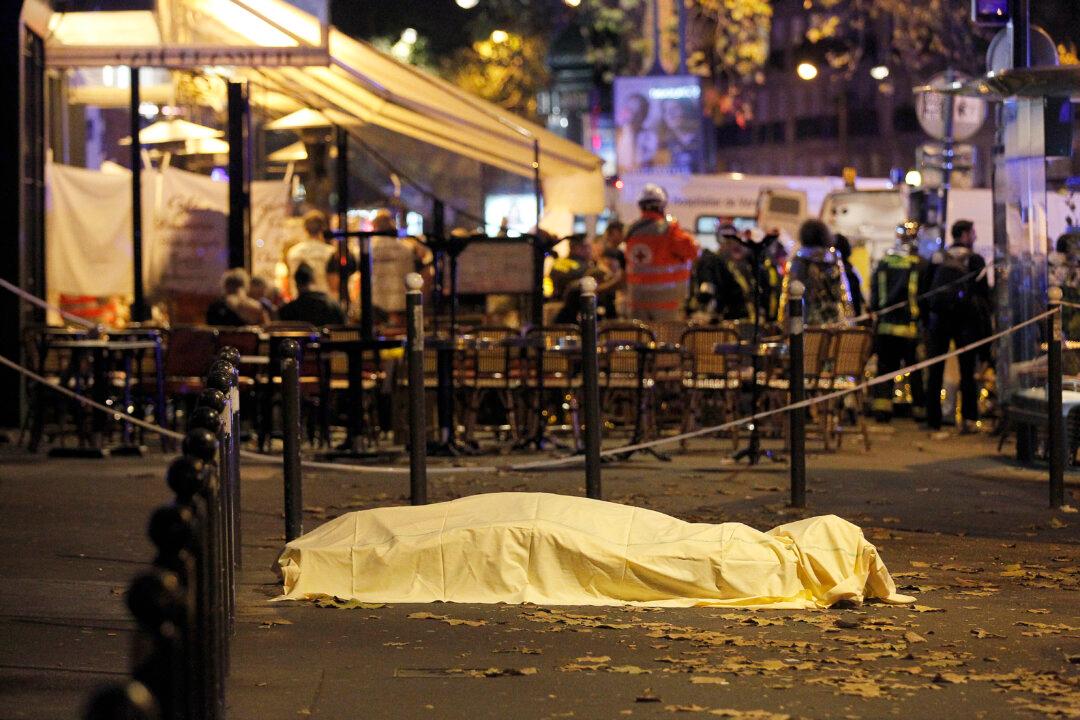

Organized and carried out largely by European citizens, the recent terror attacks in Brussels and Paris served as a harsh reminder of the growing threat of home-grown terrorism in Europe. To discover what is drawing European nationals to join the jihad and why governments are struggling to contain the terrorism threat, we talked to Anne Speckhard, a psychologist from Georgetown University who has dedicated her work to unraveling the motivations of terrorists.

ResearchGate: You have interviewed hundreds of terrorists over the course of your career. I’m curious as to how you find these people, and whether they are actually still out in the public sphere?

Anne Speckhard: It depends where they are really, if you go to Gaza or the West Bank, you find the people who are organizing suicide bombers, and you can talk to would-be suicide bombers. What I actually had to start telling people was “don’t tell me if you’re operational.” I don’t want to know and be in that position of deciding whether I should alert the authorities or not. My work is totally based on trust, so I don’t want to turn around and turn someone in.

In places like Iraq, I worked in prisons where plenty of terrorists are held. In Belgium, I talked to someone who was part of ISIS as it was forming, and also a lot of ISIS defectors—people who are not currently practicing as terrorists.

RG: How do you convince former or would-be terrorists to speak to you?

Speckhard: By building trust. You have to conduct a lot of interviews, including with people from the community. In Belgium, I’ve been doing interviews for years and years over the course of my research and in conjunction with my work for the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism. I spent a lot of time talking to North Africans, and asking them what it is like to be living here as a second generation immigrant Muslim. You start talking to one person, and then just work your way in. If the community thinks you’re trustworthy, eventually you get to your target.

RG: How are countries handling people who are returning from fighting for ISIS in Syria or Iraq and what does this have to do with extremism rising here?

Speckhard: I think every country is struggling with how to deal with this issue. There are literally thousands of people who have gone to Syria and Iraq, and right now there is a question of what we are going to do with them if and when they return.

I believe the prevention and intervention programs should focus at least in part on the families. When I talked to family members in Belgium, they told me that when their family member in ISIS calls home to talk to their family members, they assume intel is listening. But nobody comes to talk to them, nobody calls and gives them advice on what to say to encourage their sons or daughters to come home. What that tells me is that the authorities may not be that interested in getting these ISIS cadres back home. In a lot of countries, I think they have the view that—well, they decided to join ISIS, so let them fight and die there. I can understand that. But now we are seeing they can also quite easily return and plot against their own countries, so I think we might want to take a more active stance.

RG: What would you recommend countries do with these people that are returning from Syria and Iraq?

Speckhard: I would treat every single person extremely seriously. I think everyone who is arrested should go through court proceedings, be interrogated, and not immediately be released, but rather be put through a program. The program should be highly therapeutic, it should have consultation from people who understand Islam and can argue against the ideology of ISIS, and tell them well you think you’re following Islam, but where in your scriptures does it say you can do this? If they’ve been ideologically convinced, then let’s unconvince them. I am a psychologist, so I would ask what need inside the person is this extremism meeting? What is hurting in your life that makes you want to join a terrorist group in the first place? Then address both.