As difficult as it is to run an independent media outlet, there’s a company making it substantially harder.

Its name is NewsGuard. The company claims to rate online content, including from media outlets, for trustworthiness, but a closer look shows it does much more than that—its business model produces censorious pressure on news organizations. An investigation by The Epoch Times has revealed troubling questions regarding the quality of and the agenda behind NewsGuard’s offerings.

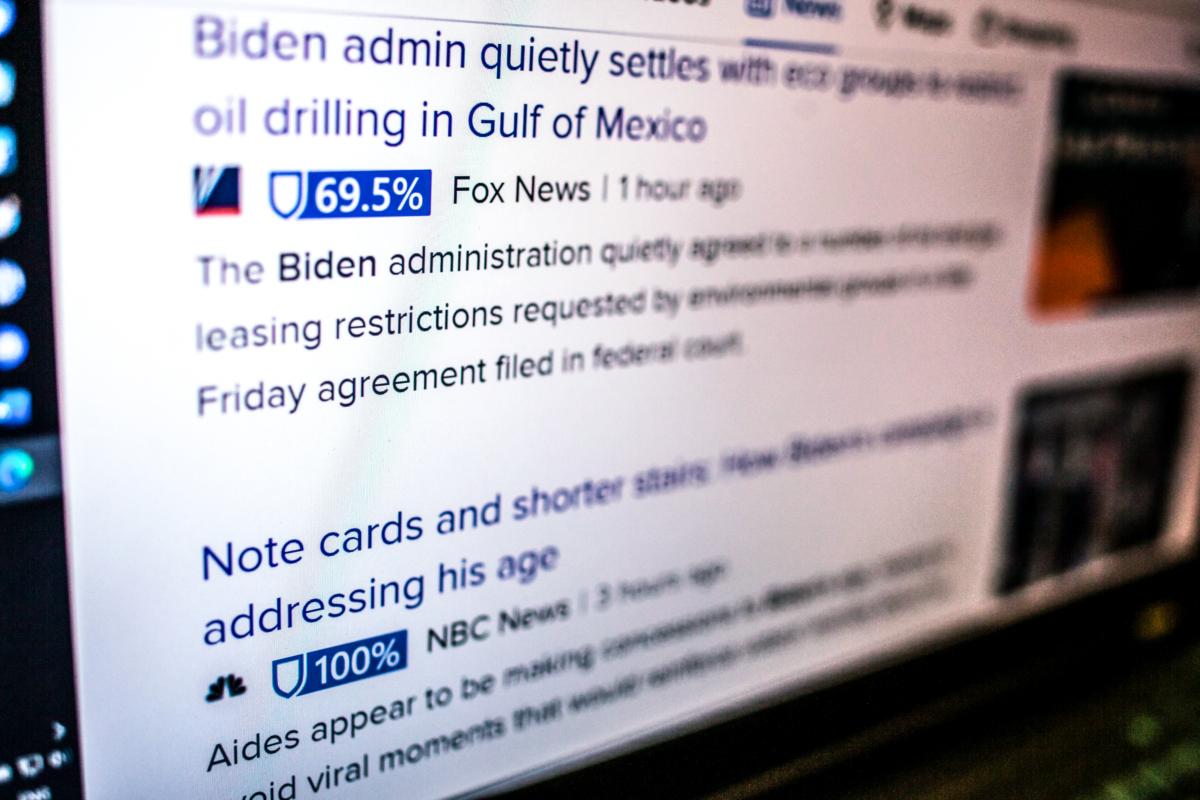

Founded in 2018, NewsGuard dispatches its “analysts” to prepare reviews of online content creators and to issue ratings “to help readers have more context for the news they read online.” The ratings display as small badges with scores next to search results.

That, however, represents only a small part of the picture. The bigger picture shows that NewsGuard’s most potent function stems from its relationships with advertising agencies, which have steered their clients to cut off advertising dollars for content creators disfavored by the company’s “analyst” reviews. As it so happens, corporate, establishment-friendly media tend to receive high scores while independent media skeptical of the establishment tend to receive low scores, even if they adhere to high journalistic standards.

Subjective Criteria

NewsGuard presents itself as objective and nonpartisan. Its ratings, the company says, measure media quality on nine criteria, including transparency of authorship and ownership and adherence to standard editorial practice, such as issuing corrections and labeling opinion pieces. In practice, however, most of the score boils down to whether the media present content that is truthful according to NewsGuard’s opinion.The first criterion specifically looks at whether the target repeatedly publishes false claims. Another examines whether it publishes news “responsibly.” But failing the first one means failing the second one, NewsGuard explains on its website. Yet another criterion is whether the target uses accurate headlines.

Again, if the headline says something NewsGuard considers to be untrue, that counts as a failure. Another criterion looks for a policy of regularly correcting errors—or what NewsGuard considers to be errors. Together, these four criteria add up to more than 60 points of the 100-point score.

Even if NewsGuard can’t find anything to dispute, it can still dock points if the target doesn’t sufficiently represent opinions the company would like to see.

Such content providers “egregiously cherry pick facts or stories to advance opinions,” it argues.

Meanwhile, at least 60 points are needed for NewsGuard to issue its rating of “credible.”

This methodology becomes particularly problematic when NewsGuard itself is wrong on the facts. For example, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the company considered false the notion that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was leaked from a lab in Wuhan, China. If a news outlet with a perfect score responsibly reported on the extensive circumstantial evidence indicating a lab leak, it ran the risk of NewsGuard decimating its score and falsely labelling it an “unreliable” source that “severely violates basic journalistic standards.”

The COVID-19 origins issue was a rare case in which NewsGuard eventually issued a correction, though it only went as far as saying that the lab leak hypothesis couldn’t be completely ruled out.

While fact-checking others, NewsGuard apparently has its own opinions to advance. There have been many examples in which media outlets found themselves in NewsGuard’s crosshairs for publishing views that question establishment orthodoxies on topics such as climate change, vaccine safety, COVID-19 restrictions, the Ukraine war, the World Economic Forum, and others. On these issues, NewsGuard seems to act as a guard of the establishment narrative, demanding that content creators toe the line.

“I’ve had interactions with them where it was very obvious that they were anything but objective,” said John Tillman, chairman of the nonprofit Franklin Foundation, which runs newswire service The Center Square.

More often than not, outlets poorly rated by NewsGuard tend to be on the right side of the political spectrum.

The Media Research Center (MRC), a conservative media watchdog, reported that NewsGuard gave left-leaning outlets scores 22 points higher on average than right-leaning outlets. The 2021 report was based on a review of NewsGuard ratings for more than 50 major news outlets sorted for left or right bias by AllSides, a company that measures media bias based on blind studies of content and editorial reviews.

Newsguard criticized the MRC report, saying it cherrypicked the outlets for the study and that the sample was too small. MRC retorted that the list included all news outlets reviewed by AllSides.

“Unlike the major fact-checking organizations, NewsGuard at least lives up to its name in that it’s a guard for the left’s news,” Matt Palumbo, researcher for conservative podcast “The Dan Bongino Show,” writes in his new book “Fact-Checking the Fact-Checkers.”

In November 2019, NewsGuard contacted the website RealClearInvestigations (RCI) and questioned its use of anonymous sources to reveal the alleged identity of the whistleblower who initiated the impeachment of President Donald Trump. RCI responded by asking NewsGuard if it was reaching out to The New York Times, The Washington Post, CNN, NBC, or BuzzFeed to question their use of anonymous sources. NewsGuard reportedly didn’t respond.

When conservative education platform PragerU was slapped with a red label by NewsGuard, PragerU CEO Marissa Streit attempted to rectify the situation in good faith, she said.

“We really believed it was a mistake,” she told PragerU founder Dennis Prager during an interview on his podcast.

In response, she received “basically a list of demands,” she said.

NewsGuard wanted PragerU to stop criticizing the COVID-19 lockdown policies, stop questioning the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines, stop talking about any COVID-19 treatments not endorsed by the government, stop questioning the seriousness of climate change—and the list went on.

“Part of their demands were basically dictating to us what kind of content we’re allowed and not allowed to share,” she said.

NewsGuard also demanded a list of PragerU’s donors, which the nonprofit refused to share out of concern that the donors would be targeted.

“They want to smear these people. That’s the only reason they want their names,” Mr. Prager said.

Ms. Streit did try to make changes to satisfy some of NewsGuard’s demands and to see how it would respond.

“The goalposts kept changing. Every time we would make a change, they would want more changes,” she said.

When PragerU commentator Amala Ekpunobi did a podcast questioning the motives of the World Economic Forum, NewsGuard demanded that the video be taken down, Ms. Streit said.

In Mr. Prager’s view, NewsGuard lacks respect for the pursuit of truth through differences in opinion.

“I still haven’t noted what did we say that’s misinformation, as opposed to [an opinion on which] honorable people can differ,” he said.

The bad rating caused PragerU’s video-hosting provider, JW Player, to abandon it, Ms. Streit said.

“They are powerful in a very bad, malevolent, malicious, destructive way,” Mr. Prager said.

NewsGuard has argued that its process is fair because it reaches out to the rated outlets for comment and includes the comments in the rating writeup.

Yet based on PragerU’s experience, it appears this practice may well be a mere formality and whatever arguments the outlets present don’t affect the final rating. Sooner or later, it seems, the targeted outlets simply give up and write off NewsGuard from that point on.

Anthony Watts and Charles Rotter run WattsUpWithThat.com, a blog for content skeptical of the narrative about the catastrophic consequences of climate change.

In their view, NewsGuard is not acting in good faith.

“They are purposefully focused on destroying the credibility of websites they don’t like,” Mr. Watts, a fellow with The Heartland Institute, told The Epoch Times.

Earlier this year, NewsGuard staffer Zack Fishman reached out to Mr. Watts about several articles. One mentioned that the arrest of climate activist Greta Thunberg was “staged.” Mr. Fishman took issue with that, saying it was a real arrest. But Mr. Watts explained that he was talking about the manner in which Ms. Thunberg was arrested. A video circulating online showed that the police officers arresting her were posing for pictures holding her while she was smiling and laughing before they led her away.

“It boils down to a disagreement with the reviewer,” Mr. Watts said.

“They apply these sort of credentialist straw man games,” Mr. Rotter said.

“It’s like, ‘We found this study that contradicts what this person said, therefore you’re wrong.’”

Mr. Fishman brought to Mr. Watts’s attention three or four articles with claims he was able to contradict. But the site has posted tens of thousands of articles. NewsGuard itself suggested its ratings shouldn’t be a reflection of the factuality of a small number of specific pieces of content.

NewsGuard has argued that what it looks at is journalistic criteria—when it points out errors, are they corrected?

But Mr. Watts wasn’t refusing to correct errors. He believed those weren’t errors to begin with, but rather issues of legitimate disagreement and opinion.

Establishment Guard

According to Mike Benz, former head of the digital desk at the State Department and now head of the Foundation for Freedom Online, NewsGuard is part of a broader censorship industry that has emerged over the past six years or so. The industry players aren’t primarily partisan, he noted, but rather pro-establishment. Right-leaning outlets can receive high NewsGuard scores—as long as they follow the establishment’s narratives on specific topics.The industry was born in response to the wave of populism that has swept the West since 2015, starting with Brexit and the election of President Donald Trump, and continuing with the rise of major populist leaders in other countries, including Marine Le Pen in France and Matteo Salvini in Italy, Mr. Benz explained.

The establishment blamed online media, including social media, for citizens voting the “wrong” people into power, he said.

“From the 1940s until the present, there has been this bipartisan conception of foreign policy,“ he said. ”There is this uniparty axis that was being broken apart by the rise of free and unfettered news online that was growing to such popularity that the gatekeepers of national security state-aligned media, such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the majors, like CBS, ABC, NBC, were now no longer the dispositive forces on elections around the world, particularly in the United States and across the EU.

“NewsGuard basically grew out of this soup in 2017 as the national security state and various opportunists on both sides of the political aisle, in particular the neoconservative wing of the GOP and pretty much all of the Democrat Party, except the anti-war left, joined together with various elements of the national security state, including the Pentagon, the State Department, and the intelligence services, to come up with basically a plan to end the popularity and availability of alternative news online.”

Mr. Tillman reached a somewhat similar conclusion.

“What they’re really trying to do is control information flow, because they don’t like the democratization of information,” he said.

Other NewsGuard advisers include Anders Fogh Rasmussen, former secretary-general of NATO; Arne Duncan, former education secretary under the Obama administration; Don Baer, former Clinton White House spokesman; and Tom Ridge, the first head of the Department of Homeland Security, under President George W. Bush.

Its reach extends beyond American borders to Canada, Australia, Europe, and increasingly other parts of the world, with an apparent goal of global, ubiquitous coverage.

Its ratings are also utilized by other parts of the censorship industry, such as researchers and operatives, including those funded by the U.S. government, who are developing tools to detect and challenge disfavored views online.

Pushed From the Top

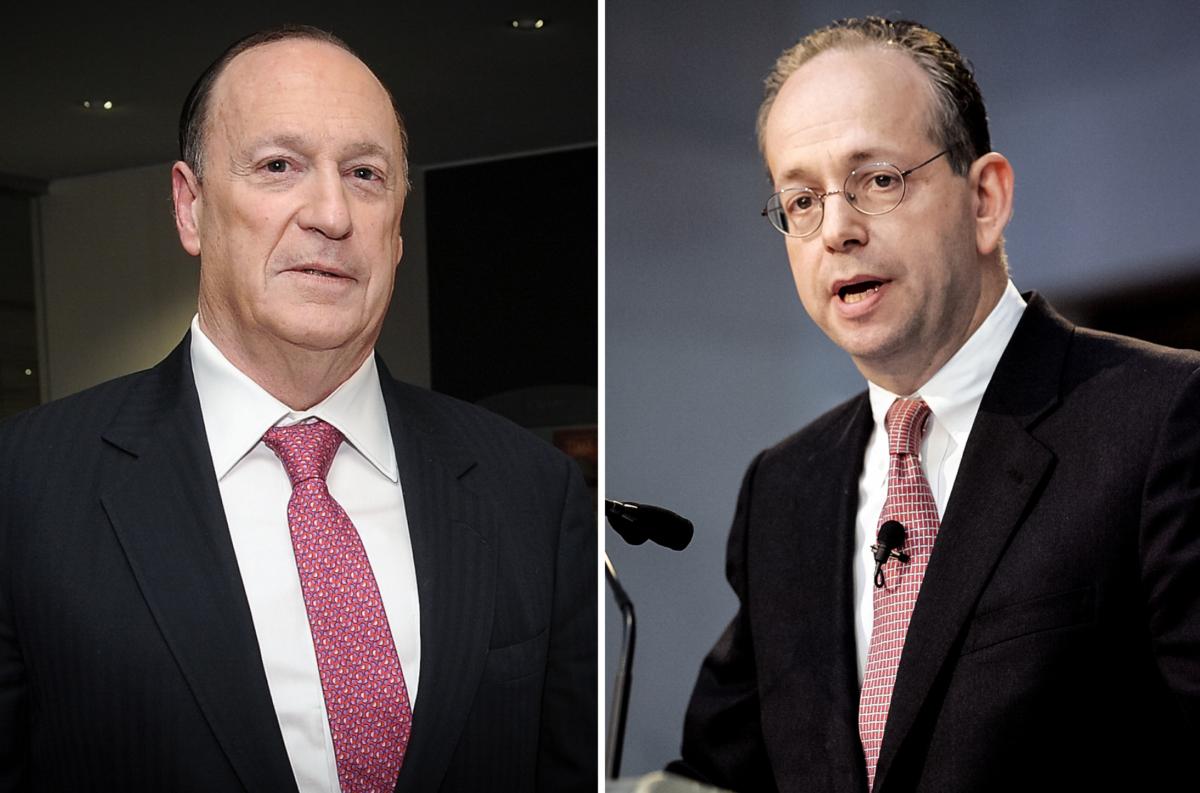

NewsGuard was launched in March 2018 by Steven Brill, former founder and head of several media organizations including The American Lawyer magazine and Court TV, and Gordon Crovitz, former Dow Jones executive and a former publisher of The Wall Street Journal.The company presents its product as giving more power to its users.

The company often describes its rating as a “nutritional label”—merely providing the public with useful data.

But the opt-in model, where customers have to pay to subscribe and download an app or an internet browser extension, seems to have hit a popularity wall.

It’s “analysts” get paid $70,000 to $80,000 annually, according to Glassdoor.

Based on these financial figures, individual user subscriptions would appear to only cover a portion of the company’s running expenses.

That indeed appears to be its business model; more than catering to the public, the company seeks corporate and government clients. By all accounts, it’s managed quite well on that front.

In addition, Microsoft also sponsors NewsGuard licensing for libraries.

“We’ve been able to get our news reliability ratings tool into more than 800 public libraries, where 7 million public library patrons use NewsGuard when they go to the library for their broadband access. And we’re already being used in dozens of public schools and universities, as well as independent schools,” Mr. Brill said in a January 2022 press release.

The release announced NewsGuard’s partnership with the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), the second-largest U.S. teachers union, which licensed NewsGuard subscriptions for all of its 1.7 million members.

The AFT is a major political lobby for various progressive causes and a large source of campaign funding for the Democratic Party.

In 2021, NewsGuard received a nearly $750,000 Pentagon contract for a project called Misinformation Fingerprints.

NewsGuard also applied for funding from DARPA, the Pentagon’s military technology investment arm, according to information on the LinkedIn profile of NewsGuard’s former project manager. It’s not clear whether the funding materialized.

According to its website, its top investor is Eyk van Otterloo, co-founder of a $1.3 billion investment fund and former owner of Chemonics International, a development consultancy that has derived almost all its revenue from U.S. foreign aid grants and contracts—worth more than $14 billion—since 2008.

Chemonics employs consultants to travel the world to set up development programs for “diversity, equity, and inclusion,” fighting climate change, managing “sustainable development,” and “strengthening systems of democratic governance to ensure accountability, justice, and inclusion.”

Populist political movements commonly propose reducing or even abolishing foreign aid, which, given the company’s historic revenue sources, would likely devastate Chemonics.

The company transformed to employee ownership in 2011, but Mr. Van Otterloo remained on its board until 2019.

‘Political Shakedown’

NewsGuard’s top corporate investor is Publicis Groupe, the third-largest ad agency in the world.Publicis’s involvement appears central to NewsGuard’s modus operandi. In fact, Publicis Chief Technical Officer Steve King sits on NewsGuard’s board of directors.

Publicis has counted among its clients giant corporations including Disney, Verizon, Bank of America, and Pfizer.

Moreover, a major part of the retail industry uses its products to manage advertising.

NewsGuard has also cultivated affiliations, partnerships, or licensing agreements with other top advertising houses in the world, including Omnicom Group and Interpublic Group (specifically its digital arm IPG Mediabrands).

By enmeshing itself in the advertising industry, NewsGuard has positioned itself to steer advertising spending—a major source of income for the media industry.

Corporations commonly hire ad agencies to place their ads. NewsGuard, in turn, through its rating system, tells the agencies which media outlets are “safe” and which are “unsafe” to advertise on.

This leverage weighs heavily on smaller, independent outlets that often depend on “programmatic” or automated advertising. They offer ad space on platforms that sell it in bulk. Ad agencies or individual advertisers then pick which ad spaces to buy based on audience data. Usually, the process is automated. And when ad agencies insert the NewsGuard filter in the middle of the selection process, small, independent outlets disfavored by NewsGuard’s ratings won’t sell their space.

Large, corporate media, on the other hand, can be virtually immune to poor NewsGuard scores, even if they receive them. They are themselves immensely valuable clients to the ad agencies and can negotiate with them directly.

Mr. Brill and Mr. Crovitz suggested that they didn’t start NewsGuard with the idea of partnering with advertisers, according to a January 2019 New York Times report.

“For them, it’s the whole problem of fake news being an issue for ‘brand safety,’” Mr. Brill told the paper. “I hadn’t even heard that term until we looked out for investors.”

Meanwhile, services like NewsGuard are pushed by the European Commission, the executive body of the European Union, through its Code of Practice on Disinformation, a voluntary set of guidelines for advertisers and tech platforms meant to reduce “disinformation” online. Last year, the code was updated with rules for companies “participating in ad placements” to “commit to defund the dissemination of Disinformation” by improving “the policies and systems which determine the eligibility of content to be monetised, the controls for monetisation and ad placement, and the data to report on the accuracy and effectiveness of controls and services around ad placements.”

A week later, the Global Alliance for Responsible Media (GARM), an initiative launched by the giant industry group World Federation of Advertisers, added “misinformation” to the list of online harmful content that shouldn’t be advertised on.

“These new standards are only the beginning,” Mr. Brill said in the release. “As policymakers continue to learn of the extent and impact of the monetization of misinformation online, the enactment of further regulations on this topic is all but inevitable.”

NewsGuard’s role in having advertisers defund outlets it disfavors “gives away the actual game,” Mr. Tillman said.

“If all they wanted was transparency, they would simply do their rating, put it out there, and let the public make their own decision whether it likes that rating or not. But that’s not good enough.

“They want to demonetize people. And that tells you they have an agenda besides judging the news by their own standards.”

NewsGuard’s advertiser defunding efforts have caught at least some negative attention from the government.

“This is a liberal organization, funded by liberal groups trying to do this— trying to discredit conservative information,” he said. “The one thing I firmly believe in, the freedom of the press. You have a right to deliver the news and people have a right to decide one way or another. But we cannot allow them to continue doing what they’re doing and you’re going to see within hearings we’re going to bring light to this.”

“My concern is, we have a third-party group that shows up and says, ‘We’re going to start grading you,’ and issues demands on the way you present content. I see that as an attack on Florida businesses,” he told The Epoch Times.

He called it “a political shakedown.”

“They’re telegraphing, ‘You need to act more like The New York Times or NPR, and if you’re not, then you’ll receive a poor grade and then your advertising will dry up,’” he said, later adding that the company is “literally trying to discredit somebody through a scoring system in order to hurt them financially.”

On the flipside, NewsGuard’s issuing of perfect scores to legacy outlets creates false credibility, he suggested.

“Honestly, I think the mainstream media’s record has not been good,” Mr. Patronis said, pointing to a number of instances where such media, according to critics, continually misinformed the public on major issues, including facts regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of Hunter Biden’s laptop before the 2020 election.

“I just don’t think you can rely on The New York Times or the NPRs of the world for our most important news information,” he said.

Mr. Patronis suspects that NewsGuard serves to shore up ad revenue for these legacy media.

Empty Credentials

NewsGuard claims its reviews are conducted by “trained journalists.” That’s not always the case, or may be a long stretch, based on information its current and former workers shared on online professional platforms, such as LinkedIn.It appears many of its reviews have been done by interns with no background in professional journalism. A typical review, it seems, would be conducted by a young journalism graduate with limited work experience. Some only list previous jobs reporting on lifestyle topics, such as food and art. Others boast as their experience producing progressive social commentary pieces, such as “Deconstructing TikTok.”

Mr. Fishman got his master’s degree in journalism at Northwestern University in 2020 and then spent about a year at Fastinform, a small New York media startup, before joining NewsGuard. He’s since progressed to the role of “senior analyst.”

NewsGuard has about a dozen “senior” and “staff analysts” and about two dozen part-time “contributing analysts.” Their job is to churn out up to two media outlet reviews a day. Thousands of such writeups are then funneled to one of about 15 editors for an additional check, and Mr. Brill and Mr. Crovitz allegedly take a look, too.

Given that NewsGuard claims to continually rate more than 8,000 content producers, it’s not clear how such reviews could faithfully gauge the quality of entire media organizations, including the accuracy of their reporting on complex, controversial topics.

As for the political views of the staff members, they lean progressive. The online footprint of a typical worker demonstrates a commitment to progressive causes, from climate change and social justice to preferred pronouns in social media bios. Some seem to have used their NewsGuard stint as a springboard to employment at progressive and pro-establishment outlets, including NPR, The Atlantic, HuffPost, and CNN.

“I knew I wanted to do audience engagement, and I wanted to find a role that was more focused on that eventually.”

During her six months at NewsGuard in 2019, she “created an editorial process for factchecking,” according to her LinkedIn profile.

In 2020, she landed a job at HuffPost as an audience editor, mainly browsing social media for article topics. She also writes on occasion, including a recent piece titled “Taylor Swift Is Apparently Dating an Alleged Racist—And Is Now Using a Black Woman to Cover Her [Expletive].”

Ironic Founders

Mr. Brill and Mr. Crovitz both spent decades in the news business and, given their past comments and endeavors, their running of NewsGuard could be seen as ironic.Mr. Crovitz spent much of his career at Dow Jones & Co., which runs The Wall Street Journal and several other publications. He made it to vice president in 1998, and he was named the Journal’s publisher in 2006. But he left the following year when the company was taken over by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp.

Mr. Murdoch’s takeover was controversial. Some staff left the Journal over concerns that the new owner would influence the paper’s editorial line.

Such concerns appear just as valid today. The Washington Post is now owned by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos; CNN is owned by Warner Bros. Discovery; NBC is owned by Comcast; and NPR is partly funded by the U.S. government.

Yet the NewsGuard of today doesn’t even attempt to question the ownership status of legacy media. It would only go as far as noting state ownership or funding of foreign outlets, like Russia Today or those run by the Chinese Communist Party.

Mr. Brill, meanwhile, knows intimately how difficult it is to start a media company from scratch.

In the 1970s and 1980s, he founded The American Lawyer magazine and Court TV. He exited both companies in 1997 after he couldn’t convince Time Warner to sell him its share of the companies.

In 1998, he founded a media watchdog called Brill’s Content. His focus at the time seemed quite different from NewsGuard’s. It was the corporate establishment media he was concerned about back then, warning that corporations that own media outlets could affect their coverage. He was affected by this personally at Court TV when Time Warner pressured him to spike a profile of a Federal Trade Commission official because it could affect the company’s pending merger.

He complained about media’s lack of accountability, promising, “We can make it actually cost something for the NBCs of the world to mess up.”

He lauded the arrival of online media as players capable of getting around the legacy gatekeepers.

He also warned about government influence on media.

“The only thing worse than lack of accountability is making the press accountable to the government,” he said.

But Brill’s Content closed its doors after three years.

Today, NewsGuard hands out perfect scores to corporate outlets but penalizes independent media for not toeing official narratives closely enough.

In 2009, Mr. Brill partnered with Mr. Crovitz to found a venture that was to help newspapers set up paywalls. They sold the business in 2011 for about $35 million.

Mr. Brill then went on to author several nonfiction books, most recently in 2018 “Tailspin: The People and Forces Behind America’s Fifty-Year Fall—and Those Fighting to Reverse It.” The book details a litany of American ills, from poorly maintained infrastructure to high health care bills, and it places the blame largely on lawyers and bankers, casting the government as a victim that has been tricked and co-opted.

His perhaps greatest claim to literary fame stemmed from his 2015 book “America’s Bitter Pill: Money, Politics, Back-Room Deals, and the Fight to Fix Our Broken Healthcare System.”

The book shed light on the questionable practices in the health care and pharmaceutical industries.

Ironically, today’s NewsGuard has relentlessly pursued critics of Big Pharma who have pointed out flaws in the COVID-19 vaccines.

Mr. Brill now sits on his board with a top executive of Publicis, the same company that’s being sued by the state of Massachusetts for helping Purdue Pharma boost sales of opioid drugs that have been blamed for an overdose epidemic that has killed more than half a million Americans. Publicis collected more than $50 million from Purdue before the pharma giant was sued into bankruptcy in 2019.

Mr. Brill seems to have different concerns now.

“My personal opinion is, there’s a high likelihood this story is a hoax, maybe even a hoax perpetrated by the Russians again,” he said.

He then criticized social media for blocking the story, arguing that they don’t have the relevant expertise to do so. Instead, he suggested, social media platforms should partner with NewsGuard—let his company sort out what is true and what is not.