The galloping rhythms, the chaos, the fun. Of old Dr. Seuss, there was only the one.

March 2, 2014, would have been Dr. Seuss’s 110th birthday. Happy birthday to him!

He was born Theodor Seuss Geisel in 1904 in Springfield, Mass., and wrote and illustrated 44 books for children before he died in 1991. He won a Pulitzer Prize in 1984. He started out in advertising, and could have made his career there. But when he switched to writing and illustrating children’s books in 1937, he transformed the field.

Books for beginners were lamer than lame. They were stale and didactic. They were boring and plain.

Until Geisel wrote And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. While crossing the Atlantic by ship in 1936, he passed the time by setting words to the rhythm of the engines. That was the genesis of his irresistible beat, as danceable as swing music.

According to Random House, “Depending on the version of the story he tells, either 20, 26, 27, 28, or 29 publishers rejected the book.” Geisel was walking down Madison Avenue, ready to throw his first classic away, when he ran into a classmate who had just gotten a job as a children’s book editor for Vanguard Press. They went up to his office and signed a contract for Mulberry Street. Geisel said, “If I’d been going down the other side of Madison Avenue, I would be in the dry cleaning business today!”

That encounter paved the way for the immortal Cat in the Hat, Green Eggs and Ham, Horton Hears a Who, The Sneetches, and many more.

Geisel started doing 220-word vocabulary books as primers for new readers in 1955 after a 1954 Life magazine story about American students lagging behind, which must be a perennial worry.

He crammed so much life into those simple books. Suspense: Can we clean up what the cat did in time? Respect: “A person’s a person, no matter how small.” Love of learning: “The more that you read, the more things you will know. The more that you learn, the more places you’ll go.”

Geisel contributed three essential qualities to American children’s literature.

First there is his draftsmanship. The lines he drew were bodacious, assured, and expressive. Those towering piles of plants and mechanisms and entities, those smiling fish and sneering grinches, flowed from his pen in fecundity like Mother Nature’s.

Then there is his sense of fairness. At Dartmouth, classmates assumed he was Jewish, and no one invited him to pledge a fraternity. He tried to speak against anti-Semitism and other discrimination through his life’s work.

Last and not least, he respects the child. His readers are persons, no matter how small.

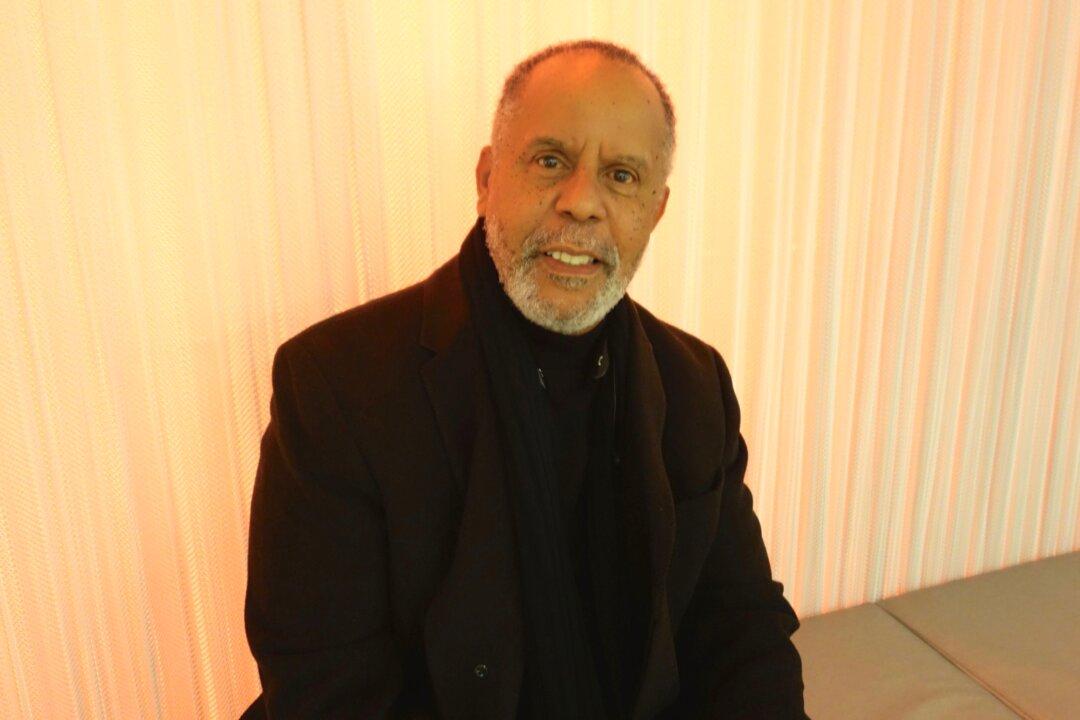

Dr. Seuss image via Shutterstock