Using penguin poo (guano), scientists have been keeping tabs on the emperor penguin species whose population numbers have been in steady decline over recent years.

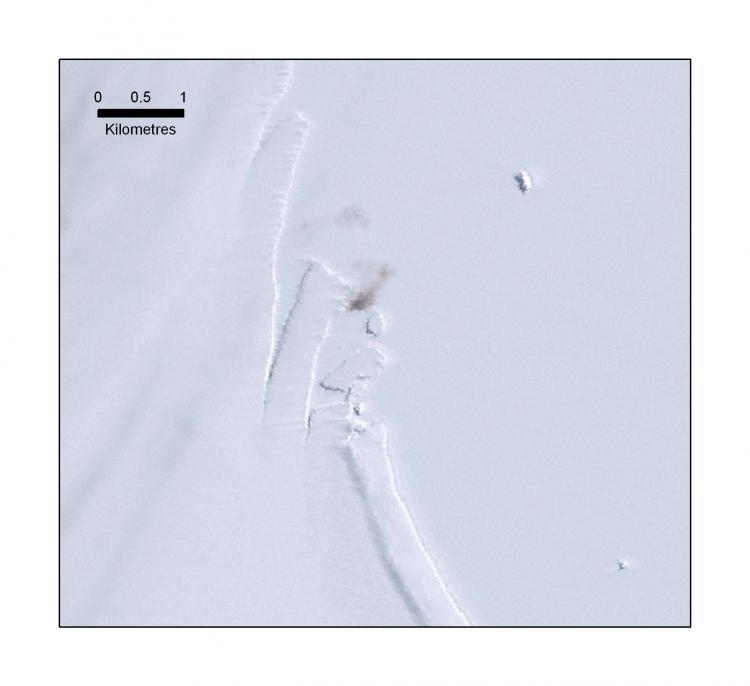

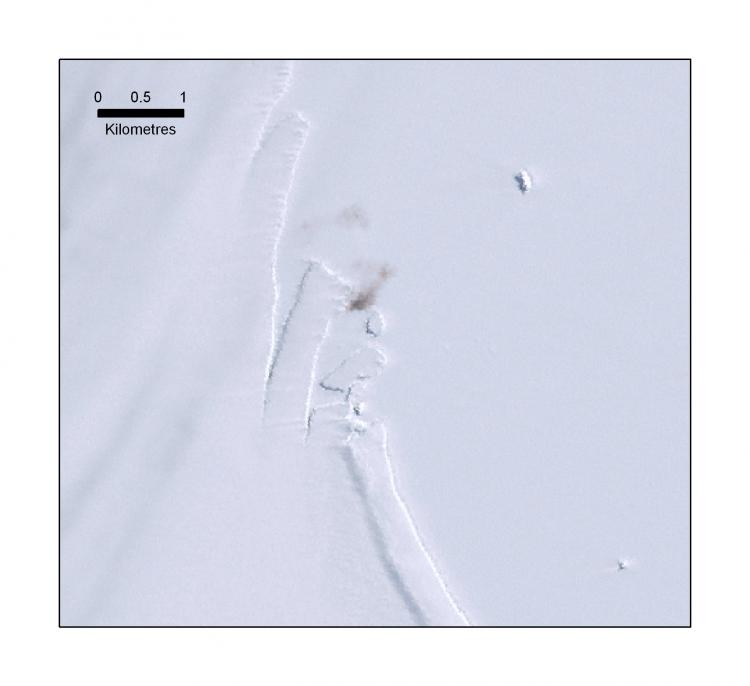

The current resolution of satellite imaging is unable to determine actual penguins; however, during their eight month breeding season on the ice, their guano accumulates until it can be seen from space.

The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) have produced the first satellite-based survey that captures almost the whole breeding distribution of the emperor penguin species over the Antarctic coast.

BAS Mapping expert Peter Fretwell told The Epoch Times, “We couldn’t see normal penguin species because they breed on rocks. They don’t stand out very well because their guano blends with the rocks. The reason we can see emperor penguins is because their guano stains are the only things coloured that way on the sea ice. They are the only bird species that breed on the sea ice.”

Emperor penguins spend a majority of their lives at sea. During the Antarctic winter when temperatures drop to -50°C they return to their colonies to breed on sea-ice, this makes it difficult for scientists to monitor them due to the harsh physical conditions and large distances.

Current estimates of the emperor penguin population ranges between 200,000– 400,000 pairs.

“It was a rather chance discovery that we could see them. They are unique in that they breed both on sea ice in the Antarctic winter and in the summer months. It wouldn’t be the life I choose, especially in the Antarctica; it gets down to -50°C even at the coast. They are an extreme species in all senses of the word.” Fretwell said.

The Cambridge-based BAS have been monitoring the effects of climate change on the sea ice in Antarctica.

Fretwell said, “It’s the sea ice factor. All predictions suggest that sea ice around the Antarctic is going to decrease, like in the Arctic which is threatening polar bears. In the Antarctic, emperor penguins have nowhere to breed so there’s a real problem with the success of their breeding and if they don’t repopulate, eventually their colonies will die off.”

Using satellite images to survey the sea-ice around 90 per cent of Antarctica’s coast, they identified a total of 38 emperor penguin colonies, of which ten were new. However, six previously known colonies were not found, suggesting the emperor penguins at risk.

Recent computer modelling studies based on over 40 years of data from a study colony in Terre Adélie in the Antarctic, have predicted that populations may decline by 95 per cent or more owing to climate change.

“By the end of this century we’ll lose a third of all the sea ice in Antarctica, but it’s not so much the amount which is important to the penguins, but the time of year it breaks up. If it starts breaking up earlier it means the chicks won’t reach maturity before they fledge and get their waterproof feathers, so they won’t survive the breaking of the ice.”

“We only discovered we could find them this way since last year…emperor penguins live quite a long time so we’re looking for a long-term change. What we’re trying to do now is establish a baseline for future monitoring.” Fretwell said.

BAS Penguin ecologist Dr Phil Trathan said, “This is a very exciting development. Now we know exactly where the penguins are, the next step will be to count each colony so we can get a much better picture of population size. Using satellite images combined with counts of penguin numbers puts us in a much better position to monitor future population changes over time.”

References:

Fretwell PT, Trathan PN. Penguins from space. Faecal stains reveal the location of emperor penguin colonies. Global Ecology and Biogeography. DOI: 10.1111/j.1466-8238 .2009.00467.x (June 2009)

Jenouvrier S, Caswell H, Barbraud C et al. Demographic models and IPCC climate projections predict the decline of an emperor penguin population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 106, 1844–1847 (2009)