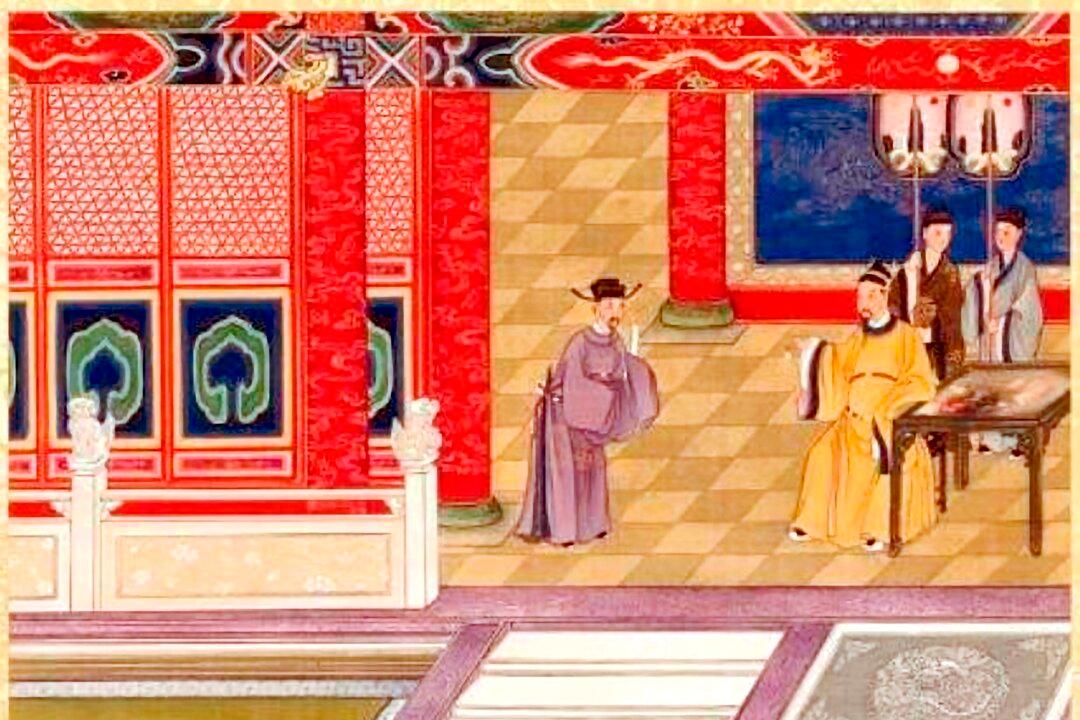

Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty (618–907) once asked his imperial historian Chu Suiliang, who kept meticulous records of Taizong’s words and deeds, whether he noted down even things that the emperor said or did that were not good.

“I would not dare not to record them,” Chu answered.

Chancellor Liu Ji added, “Even if Suiliang failed to record them, everyone else would.”

To this, Emperor Taizong replied, “True.”

This exchange was included in “Zizhi Tongjian,” a monumental book of history produced during the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127) that explored wisdom for governing a country through moral lessons from previous dynasties.

The name of the 294-chapter text, which means “comprehensive mirror to aid in government,” speaks to the practical use of the book—to serve as a mirror that reflects both the good and the bad of the past in order to help future rulers avoid repeating the same mistakes.

History Recorded for Posterity

The Chinese take great pride in having maintained 5,000 years of continuous historical records. Emperors appointed official historians to record major events such as battles, natural disasters, and diplomatic and economic affairs. Historians also took detailed notes on the emperors’ royal words and deeds in conducting state business.

It was work that particularly emphasized a truthful recording of history. Indeed, the loyalty of historians was demonstrated by their courage to keep honest accounts of everything the rulers said and did, good or bad.