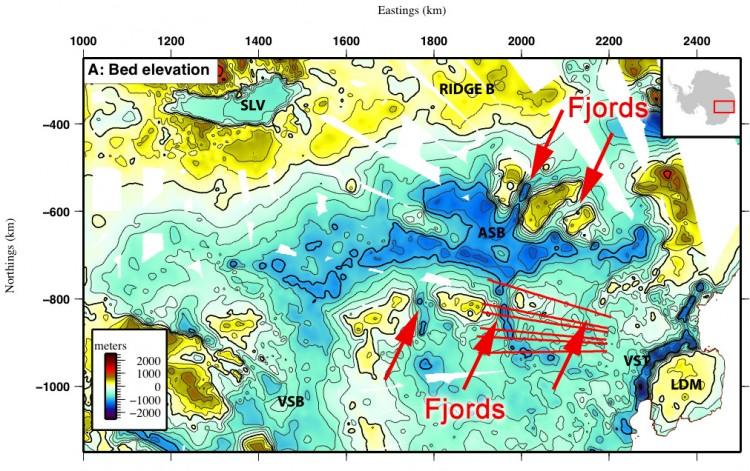

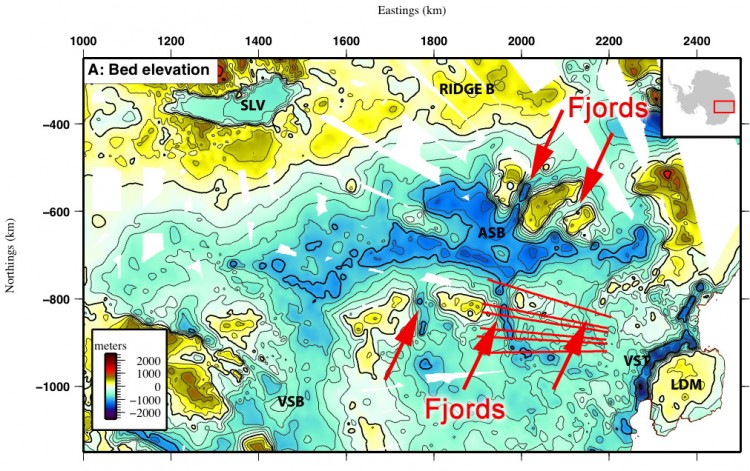

A spectacular frozen landscape has been revealed in the Aurora Subglacial Basin, one of the last unmapped regions on Earth, buried beneath 2 to 4.5 kilometers of ice and featuring some of the largest fjords in the world.

An international team of scientists used ice-penetrating radar to map the area from an airplane as part of project ICECAP, which is investigating historical changes in the East Antarctic ice sheet.

“We knew almost nothing about what was going on, or could go on, under this part of the ice sheet and now we’ve opened it up and made it real,” said lead author Duncan Young at The University of Texas at Austin’s Institute for Geophysics in a press release.

This new information will help develop models to forecast how the sheet will change in the future and its impact on global sea levels.

“We chose to focus on the Aurora Subglacial Basin because it may represent the weak underbelly of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, the largest remaining body of ice and potential source of sea-level rise on Earth,” said Donald Blankenship, principal investigator for ICECAP, in the release.

Previous research using ocean sediments and computer modeling showed that the sheet’s size has varied significantly from 34 to 14 million years ago, with up to 30 cycles of expansion and retreat in conjunction with sea level changes. This process has since stabilized.

The new map shows deep channels formed in a mountain range by ancient glaciers where the sheet’s edge shifted at various times in the past, ranging across hundreds of miles.

“We’re seeing what the ice sheet looked like at a time when Earth was much warmer than today,” Young said. “Back then it was very dynamic, with significant surface melting. Recently, the ice sheet has been better behaved.”

According to Young, knowing what the sheet looked like in the past gives us an idea of how it might appear in the future, but he does not think the shrinking will be as dramatic over the next century.

The findings are published in the June 2 online edition of Nature.

An international team of scientists used ice-penetrating radar to map the area from an airplane as part of project ICECAP, which is investigating historical changes in the East Antarctic ice sheet.

“We knew almost nothing about what was going on, or could go on, under this part of the ice sheet and now we’ve opened it up and made it real,” said lead author Duncan Young at The University of Texas at Austin’s Institute for Geophysics in a press release.

This new information will help develop models to forecast how the sheet will change in the future and its impact on global sea levels.

“We chose to focus on the Aurora Subglacial Basin because it may represent the weak underbelly of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, the largest remaining body of ice and potential source of sea-level rise on Earth,” said Donald Blankenship, principal investigator for ICECAP, in the release.

Previous research using ocean sediments and computer modeling showed that the sheet’s size has varied significantly from 34 to 14 million years ago, with up to 30 cycles of expansion and retreat in conjunction with sea level changes. This process has since stabilized.

The new map shows deep channels formed in a mountain range by ancient glaciers where the sheet’s edge shifted at various times in the past, ranging across hundreds of miles.

“We’re seeing what the ice sheet looked like at a time when Earth was much warmer than today,” Young said. “Back then it was very dynamic, with significant surface melting. Recently, the ice sheet has been better behaved.”

According to Young, knowing what the sheet looked like in the past gives us an idea of how it might appear in the future, but he does not think the shrinking will be as dramatic over the next century.

The findings are published in the June 2 online edition of Nature.