On Oct. 9, 2013, Spain’s highest criminal court indicted Hu Jintao, former paramount leader of the People’s Republic of China, for committing genocide in Tibet. The ruling brought vindication for the Tibetan plaintiffs who filed the suit in 2005, a group that included several individuals who endured years of imprisonment and torture in Chinese prisons for such “crimes” as refusing to renounce their Buddhist faith.

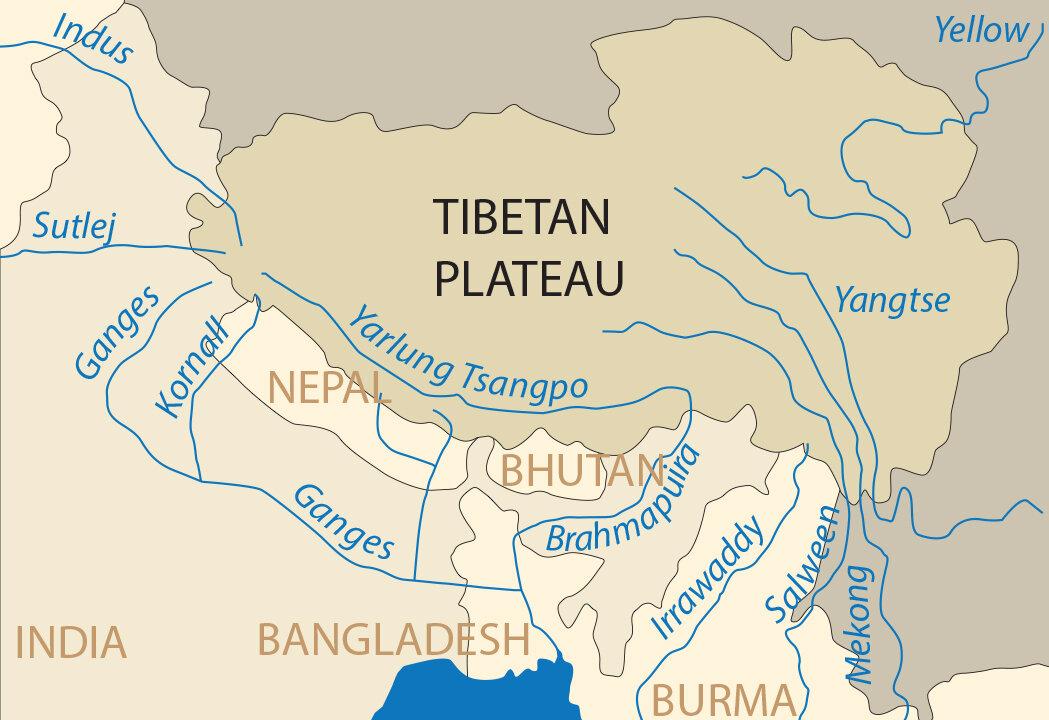

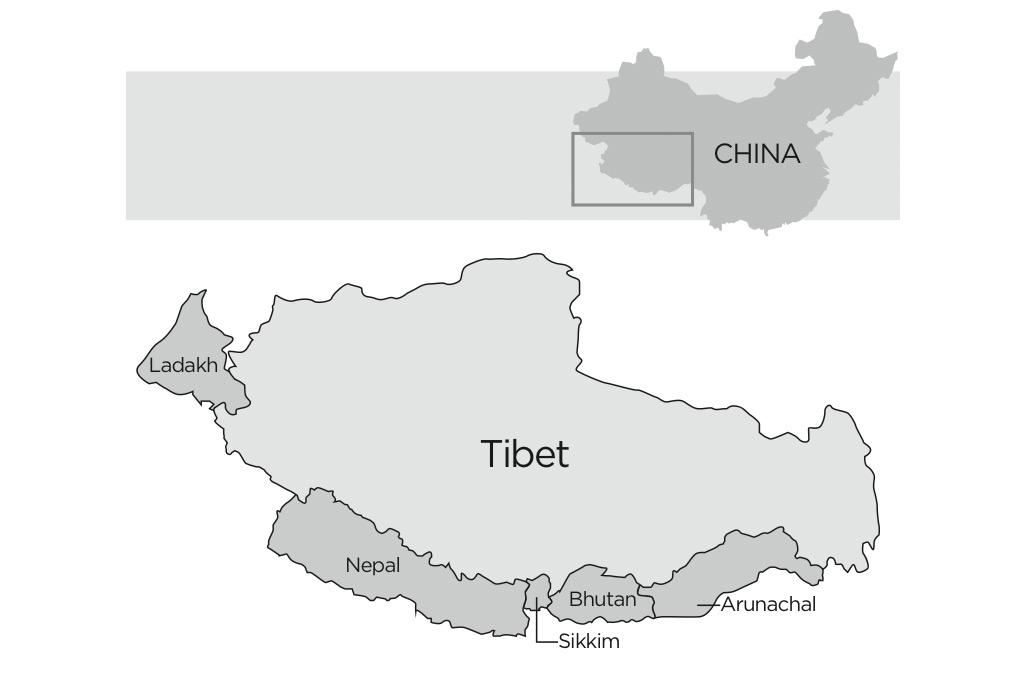

This is not the first time China has been deemed guilty of genocide in Tibet. In 1959, after a failed uprising sent the Dalai Lama and thousands of Tibetan refugees into exile in India, Nepal, and Bhutan, the Indian jurist, Gandhian freedom fighter, and lawyer Purushottam Trikomdas traveled to the International Commission of Jurists in Geneva to verify and document China’s crimes of genocide committed against the Tibetan people: over a million killed by Mao Zedong through armed conflict, incarceration, and famine.

The Commission’s report said, “The evidence points to a systematic design to eradicate the separate national, cultural, and religious life of Tibet.”

Hu Jintao, governor of Tibet before ascending to the top of the Politburo, continued Mao’s policy of “Strike Hard” against the Tibetan people, with intensified persecution of Tibetan Buddhism.

Hu Jintao was chairman of the PRC during the Tibetan uprising in March 2008, four months before China hosted the summer Olympics. He visited brutal retribution on Tibet, post Olympics. Photographs and army film smuggled out of Tibet show house-to-house raids, beatings, firing squads, and mass graves.

Propaganda

Despite the ruling of the Spanish Court last week, the PRC’s allies and apologists will likely continue to defer to the Chinese regime’s version of the Tibet story. Chinese propaganda has been highly effective. For years, sinologists throughout Western universities taught that Tibet was a society organized as a “backward serfdom,” which now enjoyed a new and welcome prosperity under China’s “peaceful liberation of Tibet.”

For years, Chinese Communist officials have referred to the Dalai Lama, the distinguished Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, as “an incestuous murderer,” “counterrevolutionary bandit,” and “an executioner with honey on his lips and murder in his heart.” This Stalinoid dementia is ludicrous, but it has obfuscated the Dalai Lama’s repeated attempts to negotiate with Beijing.

The Dalai Lama is a threat to Chinese leaders like Hu Jintao and current regime head Xi Jinping for two reasons: He is the personification of the Tibetan nation, and he is the living symbol of the Tibetan Buddhist faith.

‘Disease to be Eradicated’

An examination of the Tibet case reveals the People’s Republic of China’s hardline policies on Buddhism. For a millennium, Tibet’s monasteries functioned as township centers of education, art, and commerce in a nomadic culture.

After the flight of the Dalai Lama to India in 1959, Mao’s Red Guards looted and razed over 6,000 Tibetan monasteries. Monks and nuns were publically tortured and put to death for having “bad class status.”

The Cultural Revolution, 1966–1977, was especially cruel in Tibet. All forms of religion and folk culture, from dancing to incense burning, were banned. Long hair, worn by both men and women, was labeled “the dirty black tails of serfdom.” It took 30 years for this story to reach the international press.

Mao’s “Campaign to Smash the Four Olds” was the apex of communist pathology. The Red Guards burned temples, books, and art, and slaughtered scholars, monks, and artisans—all in the name of destroying “Old Thought.”

When the states of Southeast Asia emerged from their totalitarian confinement in the 1990s, Buddhism reappeared, and sanghas—monastic communities—were quickly re-established. But Tibet is an occupied country in bondage to the Chinese Communist Party.

The Mao Cult is far more prominent in Tibet than in central China. The communists say that Tibetan independence could “split the motherland.”

The collapse of the Soviet Union shattered the primary tenet of Marxist theory that socialism would vanquish the social stratifications of class and ethnicity. The Chinese communist flag declares a multi-ethnic state: A large star representing the Han is ringed by small stars for the Mongols, Manchus, Uyghurs, Wei, and Tibetans.

Under Mao’s social and economic experiments, China’s 60 million minority peoples were coerced into reincarnating as “red and expert” Chinese citizens.

Tibetans and other “minorities” are punished for expressions of ethnic and cultural identity. The “Strike Hard” Campaign, implemented in 1995, moments after the Clinton administration delinked trade and human rights, targets Tibet’s Buddhist clergy for extreme punishments.

It is wishful thinking to hope that Xi Jinping will bring meaningful reform when the Chinese Communist Party functions as the organizing principle of the state bureaucracy. In his first year in power, Xi Jinping has intensified Maoist “re-education” and “thought reform” in Tibet.

Tibetans who resist denouncing the Dalai Lama during compulsory “patriotic re-education” sessions receive especially cruel punishment. Since 1996, the CCP has banned all photographs or images of the Dalai Lama as “reactionary literature,” and Buddhism is officially termed a “disease to be eradicated.”

Describing Catastrophe

The 20th century was a catastrophe for the Buddhist faith, yet few scholars have examined Buddhism’s disastrous collision with modernity. Twentieth-century totalitarian governments laid waste to millions of Buddhist communities.

So how to describe the Buddhist tragedy of the 20th century? The Oxford English Dictionary defines “genocide” thus: “origin from Greek genos ‘race’ + -cide; the deliberate killing of a large group of people, especially those of a particular ethnic group or nation.”

Is “conquest” more accurate? Conquest is defined as “the subjugation and assumption of control of a place or people by use of military force.”

In any case, the world community did nothing as Tibet was invaded by China and sealed behind the Bamboo Curtain.

The Indian lawyer J.S. Verma later wrote: “Had the world first taken action when China invaded Tibet in 1951, Tibet would surely have been saved. ... China was recovering from a disastrous civil war and did not have the resources to handle two conflicts: Korea in the East, Tibet in the West. … India paid for that mistake when China secured its control over Tibet in 1959 and then invaded India in 1962.”

In his first-person account of China’s seizure of his homeland, the Dalai Lama recounts his journey to Beijing in 1955. At the state dinner, Mao turned to the Dalai Lama and said: “You see, religion is poison. It has two great defects: It undermines the race and secondly, it retards the progress of the community. Tibet and Mongolia have both been poisoned by it.”

The Dalai Lama bent his head and shuddered. “So you are the foe of the dharma after all.”

Maura Moynihan is a journalist and researcher who has worked for many years with Tibetan refugees in India and Nepal. Her works of fiction include “Yoga Hotel“ and ”Kaliyuga.”