Flight has become one of the safest means of transportation in modern times, but lessons must always be learned from every airplane accident to ensure safety in future flights. The development of commercial aviation has always depended on careful investigation of aircraft crash accidents.

However, flawless technical performance or skilled pilots aren’t the only factors involved in providing safe air travel. Safety also relies on the work of air traffic controllers who direct and maintain an orderly flow of flight traffic from gate to gate.

In the early days of commercial aviation, air traffic controllers were not in towers observing the entire airfield. These individuals simply stood near the runways and guided planes in and out of airports waving flags.

After World War II, commercial air travel grew considerably. Vacationers and business people alike increasingly chose the speed and convenience of flying when traveling to destinations hundreds of miles away, rather than spend several days on a bus or train.

As air traffic increased, pilots began using radios to communicate with controllers on the ground. Later, towers became necessary to manage the growing number of flights, ushering in the modern era of air traffic control.

Grand Canyon disaster

One particular accident from June 1956 had much to do with shaping our air traffic control (ATC) system. This highly publicized disaster took place over the Grand Canyon in Arizona. A United Airlines passenger airliner (Flight 718) struck a Trans World Airlines airliner (TWA Flight 2) over the Grand Canyon resulting in a mid-air collision. Both flights had taken off from Los Angeles airport only minutes apart.

There were no survivors from either plane, and the crash had become the worst accident in aviation history up to this point. Yet this disaster would become the inspiration for sweeping changes of ATC in the U.S.

The turboprop airplanes involved in the accident were the most modern of its time—Lockheed Super Constellation and Douglas DC-7.

In the 1950s, the system used to track flight traffic was still relatively primitive. While they were already in towers by this point, air traffic controllers would position planes on printed maps based on speed and altitude readings obtained through radio communication with the pilot.

This system only gave controllers a rough estimate of each plane’s best known position; they did not have an exact idea of an aircraft’s location. The U.S. terrain was not covered by radar in the late 50s, so planes at that time were flying by the rule: “see and be seen.”

With very little radar on the ground to track planes in the air, a craft out of radar range could only be located based on the speed and altitude estimates last reported form pilots while still in radio controlled areas.

In the 1956 flight disaster, the two planes were flying at the same altitude and almost at the same speed when they approached the Grand Canyon. Both crews had to weave around towering clouds, as flying in uncontrolled radar airspace required that they remain visible at all times.

Maneuvering over the canyon, it is believed that both planes passed by the same cloud formation at the same time, without ever knowing that they were on a collision course.

The crash was shocking to a public that had previously had a growing confidence in air travel. The collision was an alarm bell for the entire nation. Something needed to be done to prevent such accidents in the future.

The public was outraged when they learned that the ATC system was inadequate and unable to meet the demands of the increased air traffic becoming a potential for another disaster.

As a result, the government was pressured to take immediate action to solve the problem. It became clear that more radar was needed to control flight traffic, and the ATC system received a substantial update.

In 1957, congress allocated considerable funding to employ and properly train more controllers to modernize the ATC. Yet despite these steps, aircraft collisions still remained a threat.

Military/commercial coordination

In the 50s, the airspace was controlled by the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) and the military. However, the CAA had no authority over military flights which could penetrate controlled airspace with little or no warning to other traffic. As a result, a series of near misses and collisions between military and civil aircrafts continued to occur.

For example, on April 21, 1958, the mid-air collision of United Airlines Flight 736 and United States Air Force fighter jet near Las Vegas, Nevada resulted in the death of 49 people, sending both craft into uncontrolled dives toward the ground.

After further congressional hearings, the Federal Aviation Act of 1958 was passed into federal law establishing the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

FAA was given complete authority over the control of all airspace in the U.S., including military flights. Furthermore, ATC facilities, procedures, and equipment received even more updates.

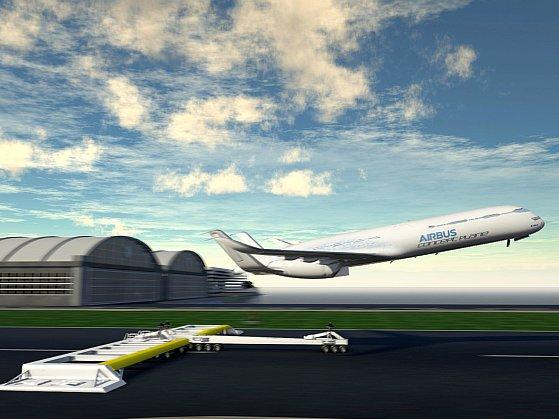

Today, planes fly in strictly controlled air corridors. The space among craft is also controlled due to the development of a nationwide radar system.

Although these improvements have contributed to safer air travel, fifty-two years later it seems the ATC system is due for another update.

Increasing demand/controllers under stress

With rising fuel costs and uncertain economic times passengers are still flying, but they are often lured by the cheap air fare offered by discount carriers. This has resulted in an ever growing number of airplanes at busy airports leading to congested runways, slow moving traffic, and increased harm to the environment from idling engines on the ground.

For example, at John F. Kennedy Airport in New York as many as 1200 airplanes arrive and depart every day, as flights have steadily increased over the past decade. There are also many craft waiting to land at any given moment, with even more on the ground awaiting permission for take off.

This growing flight traffic can test controllers’ abilities. But no matter how overwhelming the situation, they must always provide a tidy flow of traffic.

The job is not for everyone. Controllers are described as well organized, quick in math with strong self-confidence and firm decision making skills. They must possess superb short-term memory abilities, as well as excellent hearing and speaking skills.

Controllers must maintain constant communication with several pilots. They use a push-to-talk radio system, meaning that only one transmission can be made on a frequency at a time, otherwise transmissions will either merge together or block each other and become unreadable. This is an aspect that poses limitations to the current ATC system.

At every moment, controllers must coordinate a great amount of information, including airplane speed, altitude, and separation among craft. As the number of flights grow, controllers must accomplish their tasks with even greater speed and efficiency. This increases the risk of error as a single miscommunication about an altitude level or runway number may spell disaster.

The official language for ATC is English, but busy airports like JFK see planes arriving from all over the world. Pilots may speak with a thick accent and controllers must be careful to avoid any miscommunication.

Furthermore, modern passenger liners fly faster and higher than their 1950s counterparts. While contemporary radar systems are usually able to accurately determine a craft’s coordinates within a controlled area, the method is not foolproof. Radar cannot detect planes that fly out of range and the radar signal can also be obstructed by terrain or bad weather.

As the number of flights continues to grow, today’s controllers are forced to coordinate a staggering number of flights. Many believe that the time has come to re-evaluate and update the current ATC system once again so that air traffic controllers can continue to ensure safe air travel.