Let’s be honest with ourselves—The minute we think about sports, images come to mind of world-class champions and elite teams in a world of high power sports. A world where peak performance is key in an outrageously profitable sports industry.

No one thinks much about the sportsman next door, who is often also in top performance condition and excels at difficult feats. One reason could be that a zealous media does not regale such sports enthusiasts on a daily basis. But let’s not forget that they exist. Among them there are many men or women who train after work with the goal of becoming first-rate competitors.

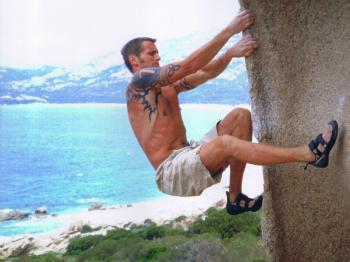

One of them is Frank Strempel, who holds down a day job as a social worker, is married and the father of two daughters.

Frank Strempel’s training day is just beginning in the evening, after a full day of work, and continues on weekends when he goes to the mountains, in hopes of conquering rock. Strempel also trains youngsters interested in climbing. He enjoys talking about what motivates him to train them, and his particular fascination with climbing.

ET: Mr. Strempel, what drives you to climb?

Frank Strempel (FS): I view myself as an experienced sport-climbing enthusiast. My consistent goal is to reach greater heights with each subsequent climb. I don’t necessarily mean that I want to scale the highest mountain. I am referring more to the level of difficulty of an ascent. I strive to advance my climbing knowledge and experience.

Furthermore, I want to test myself with increasingly difficult climbs to see my level of improvement. I am now 42 years old, and my performance is continually improving. Upon acheiving another goal, having reached the mountain’s summit after a difficult climb, I get the sense that “I’m strong, and I accomplished my goal.” It is a very thrilling feeling once you have accomplished another objective, knowing that you have done your best.

ET: What is the allure that compels you to climb?

FS: In the beginning I looked on it as a great adventure—you literally scale great heights, risking your life; you are a man and you are a hero. There are a lot of clichés I could use. But, most importantly for me, I can measure my achievements and I can give my all. One also experiences the feeling of freedom and adventure, something that is missing from everyday life.

But now I have changed, and the wish to achieve great physical accomplishments has transformed into that of placing higher value on the mental component that comes with climbing. I have gradually come to realize that any new achievement was only possible through the “mind over matter” issue. If the mind is not 100 percent involved in the effort, the body will never achieve its greatest potential. One always needs to set higher goals for oneself with new boundaries, measuring oneself against them.

My present climbs are in a category that does not allow me the opportunity to grab onto the rock or stop for a breather. One hangs from two fingers on some kind of crack, then goes on to the next crack and from there one tries to grip the next one—it’s a weird feeling. One does not even have a moment to think over the next move. Decisions have to be made in an instant. If ones mind is not 100 percent on the task at hand, if one is not sure about the specific facade one attempts to climb, when one is in doubt about one’s next move, or when one caves in to the pressure of intense stress and doesn’t focus one’s strength upon the next spot, it is extremely difficult to succeed.

I also find it extremely fascinating that one has to come to an immediate decision and within seconds, one finds out if one has made the right or wrong decision. If one made the correct decision, one moves on and if one has made the wrong decision – well, one might have an incredibly rapid descent and will possibly be saddled with a severe injury.

Being aware of the above factors give me a feeling of great strength. But, please don’t misunderstand – I’m not obsessed with the game of life or death. At the age of 25, having gone on many solo climbs, I always kept in mind my level of ability and what I could achieve at a given point in time. At the time, I had nothing that would stop a fall and all my climbs were without a rope. Yes, there were situations that were beyond my control. But, after a few years, I made another decision, “the pitcher goes often to the well, but is broken at last” – leave it alone.

ET: Can you explain a situation that was outside of your control?