INNOVATION IN TROPICAL FOREST CONSERVATION SERIES: Despite decades of attention and advocacy, tropical forests are still falling at rapid rates worldwide. Now, mongabay.com’s new special series, Innovation in Tropical Forest Conservation aims to highlight solutions to the crisis through short interviews with some of the world’s leading conservation scientists, practitioners, and thinkers about new and emerging approaches to conservation. For more of these interviews, please check Mongabay’s Innovation in Tropical Forest Conservation feed.

Dr. Douglas Sheil considers himself an ecologist, but his research includes both conservation and management of tropical forests. Currently teaching at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU) Sheil has authored and co-authored over 200 publications including scholarly articles, books, and popular articles on the subject.

“I think one of the most important recurring discussions I have with students and young researchers concerns the balance between our science and the value-driven ‘normative’ content of what we do,” Sheil told mongabay.com. “What I believe we need is a more humble, critical and evidence-based approach to forest conservation—knowing what works where and when, and learning what we can from shortcomings and failures.”

After receiving a doctorate in Tropical Ecology from Oxford University in 1996, Sheil worked as a consultant for many years before joining the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR ), where he developed and led ecological, conservation and community-based studies with local and international collaborators, mostly in East Kalimantan and West Papua. In 2008, Sheil was hired by the Wildlife Conservation Society, and seconded to Mbarara University of Science and Technology to direct a research station located within the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, a World Heritage site, in Uganda.

“Another game-changer,” Sheil says from of his experiences with international conservation work, “is democracy...Combine democracy with modern communication technology and improved information access, and it seems that governments will increasingly be held accountable. So will conservation. These changes are a double-edged sword: when conservation is popular and guarantees votes it will thrive--where it is unpopular and loses votes, it will suffer. Unfortunately, this second category is common: high-handed conservation activities, however well intended, have effectively alienated people in many parts of the tropics.”

He adds, “ Conservation is unsustainable without local support.”

“Finally,” notes Sheil, apropos to this series, “a short note of caution: new methods and new thinking offer new options and opportunities, but novelty is no substitute for critical appraisal. We need to navigate among the options, acknowledging their strengths and weaknesses, and choose approaches, however new or old, that best suit the situation.”

An Interview with Dr. Douglas Sheil

Douglas Sheil in the forest in Borneo. (Courtesy of M. van Heist)

Mongabay: What is your background? How long have you worked in tropical forest conservation and in what geographies? What is your area of focus?

Doug Sheil: I am Irish and, though I spent my first years in Africa, most of my childhood was in Ireland. I always enjoyed exploring wilder places. My first degree was in natural sciences, but as a student I got involved in various environmental projects overseas during summer breaks. These overseas experiences motivated me to abandon earlier thoughts of lab-based research in the hope that someone might pay me to do the fun stuff I did in my holidays. Luckily someone did.

After an MSc in forestry and time working on forest conservation projects with IUCN in East Africa, I went back to university for a doctorate. The doctorate was based on rainforest plots set-up in Uganda in the 1930s and 1940s, and offered a unique opportunity to track long-term processes. I finished in 1996 and, after some short contracts, moved to Indonesia to work for the Center for International Forest Research (CIFOR), where I stayed for ten years. Activities with CIFOR were varied. My main tasks included leading a project on engaging with the views of remote forest dependent communities and how these might guide conservation and forest landscape management more generally.

Another project I led examined how the management of production forests might better benefit wildlife conservation in Borneo (see Life After Logging authored with Erik Meijaard and others). Towards the end of my time in Indonesia, I also worked on a book on rain forest ecology and conservation with Jaboury Ghazoul that provided a great opportunity to look at the cutting edge of a range of broader topics related to rain forests. It is fascinating stuff—the deeper you look the more you'll find, and there doesn’t seem any obvious limit—we still have plenty to discover.

Being keen to stay close to the field, I then accepted a position as the director of a research station located within the Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, a World Heritage site, in Uganda. Officially, I was hired by the Wildlife Conservation Society, and seconded to Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST) in Uganda. Bwindi is a beautiful place, and probably among the best protected forests in Africa, but there are many challenges and opportunities for useful research, so it was a great privilege to be able to help train local students and others in such a setting.

Now, I’m in Norway working and teaching at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU). Norway is hugely influential in global discussions about the future of forests. I'll still work with field-based researchers and students and will spend most of my time on research.

I consider myself an ecologist, but my research is quite diverse and touches on many aspects of tropical forests, including conservation and management. Most of my field experience has been in Indonesia and East Africa.

The Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda hosts nearly half of the world’s remaining mountain gorillas. (Courtesy of Douglas Sheil)

Carvings of gorillas in Uganda. How does conservation benefit local people? (Courtesy of Doug Sheil)

Mongabay: Are you personally involved in any projects or research that represent emerging innovation in tropical forest conservation?

Doug Sheil: Yes, lots. I'll highlight a few.

I’m involved in several studies looking at the influence of forests and tree cover on rain and water availability. These influences remainsubstantially under-appreciated. Many exciting ideas come from my colleagues Anastassia Makarieva and Victor Gorshkov and their theory that indicates that forests play a central role in generating not only rainfall but wind patterns. I also recently got involved in a study suggesting that tree cover has a positive role on water availability in relatively arid regions—this challenges the “more trees means less water” thinking that has prevented major reforestation efforts in much of the tropics. We’re making great progress in developing and evaluating these ideas—but there’s plenty still to do.

I’m also involved in various initiatives involving conservation opportunities and outcomes in modified forest landscapes. We’re used to seeing these opportunities in temperate countries but somehow less so in the tropics. To be clear, I am very keen that we maintain large near-pristine areas wherever we can reasonably do so, and I don’t want anyone to stop investing efforts in that, but we also need conservation elsewhere. There’s a lot to be done and it isn’t always easy to reconcile diverging views. I hope we can be objective in our assessments and judgements and be ready to listen toalternate views.

I think one of the most important recurring discussions I have with students and young researchers concerns the balance between our science and the value-driven “normative” content of what we do. It’s important to distinguish these. We shouldn’t know the answer before starting the research. We need to be both skeptical and open minded to differing viewpoints and consider what evidence might change our judgements. What I believe we need is a more humble, critical and evidence based approach to forest conservation—knowing what works where and when, and learning what we can from shortcomings and failures.

I’m still exploring ways for researchers, conservationists and others to better engage with local people’s needs and preferences. There are many options for how to do that. The important point is, it isn’t hard to do and almost always brings worthwhile benefits, insights and opportunities. There are also ethical arguments about why local views matter. It is not our role to make all the choices. There are many voices that need to be heard (as in this video we made a while back in Kalimantan).

Mongabay: What do you see as the biggest development or developments over the past decade in tropical forest conservation?

Doug Sheil: Climate concerns have motivated much forest related politics and activity. Despite the controversies and slow progress, I consider the attention directed towards forests and how to protect them as positive. There is now a large audience for forest related information. Proposals and naïve approaches now are treated with greater skepticism. It can certainly be frustrating that many debates are unlikely to be resolved any time soon, but it is better that we are having the debates, as diverse principles and viewpoints are important.

In terms of larger trends, I'd highlight urbanization. Half of the world’s people already live in towns and that percentage is growing. What does that imply for conservation, land-use and food production? It isn’t a simple story. In some regions urbanization has moved people off marginal lands and facilitated recovery of forest. But such sparsely inhabited areas are vulnerable to large-scale conversion. A different set of concerns arises from declining contact with wild nature. Will people support conservation when they lack experiences and related appreciation of natural places to draw upon? How can meaningful connections between people and nature be sustained?

Another game-changer is democracy. Many countries have emerged, are emerging, or may soon emerge, from centralized authoritarian systems of government. The transition process may be turbulent, but in the long-term the decisions that determine the future of forests will increasingly depend on the views of the people most affected. Combine democracy with modern communication technology and improved information access, and it seems that governments will increasingly be held accountable. So will conservation. These changes are a double-edged sword: when conservation is popular and guarantees votes it will thrive—where it is unpopular and loses votes, it will suffer. Unfortunately, this second category is common: high-handed conservation activities, however well intended, have effectively alienated people in many parts of the tropics. An obvious case is where people have been moved off their ancestral lands without just compensation. Such interventions persist well after the colonial era. The resulting hostility to conservation authorities has led to many such local people being labelled “anti-conservation,” but this is misleading. It is perfectly reasonable to protest strongly about injustice and still embrace conservation as a societal aspiration. Far from being hostile, many of the people affected would support conservation conducted in a manner that respects local concerns. Building a national consensus in favor of conservation remains a major challenge in many tropical forest countries.

Local communities score the value of different land-cover in Kwerba Village in Papua, Indonesian New-Guinea.(Courtesy of Doug Sheil)

Mongabay: What’s the next big thing in forest conservation? What approaches or ideas are emerging or have recently emerged? What will be the catalyst for the next big breakthrough?

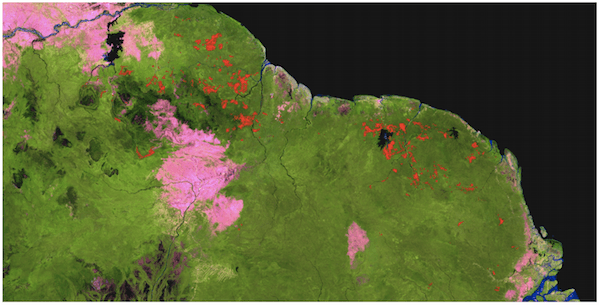

Doug Sheil: There has been major progress in data gathering and management. The availability of tree cover change data and near real time monitoring from space provides exciting opportunities. Such techniques will help us understand how systems are changing and also improve transparency and chances to respond to threats. I’m especially excited about the potential of the ESA Biomass mission, that will assess standing biomass at high resolution using radar (so clouds are no problem).

Large shifts in international and regional motivations may occur. For example, I hope that large-scale forest protection and reforestation may be favored for its role in protecting and stabilizing rainfall. But if I had to underline one change it'd be the progress of democracy. Conservation is unsustainable without local support.

The direct and indirect identification of species via genetic analyses opens many new options. I have recently been supervising one PhD student using such as approach to assess the effect of habitat degradation and conversion on the soil biota—this is really a science frontier that has been thrown wide open. We don’t know yet what we'll find.

Some shifts in how we conceive conservation approaches seem predictable. We will increasingly have to accept change and work with it rather than try to stop it. For example, translocation will likely become more common, acceptable and more mainstream. I also anticipate a fuller appreciation of the conservation values of managed, secondary and modified forests. A more nuanced approach to exotic species and novel ecosystems will also emerge in time.

I hope we'll also see a fuller appreciation of the multiple roles that people play within tropical forest. At present the positive stories are often seen as unusual anecdotes, and the negatives the general norm. That seems misleading. Consider the vast areas under indigenous control in the Amazon, Papua and elsewhere that remain forested in large part because the local people will not tolerate incursions. Engaging with these opportunities for collaboration requires less centralized command-and-control conservation and more local consensus-building and opportunistic conservation partnerships.

Finally a short note of caution: new methods and new thinking offer new options and opportunities, but novelty is no substitute for critical appraisal. We need to navigate among the options, acknowledging their strengths and weaknesses, and choose approaches, however new or old, that best suit the situation.

Mongabay: What isn’t working in conservation but is still receiving unwarranted levels of support?

Doug Sheil: The imperial approach, which imposed protected areas and policed them with military style forces, seems outmoded. Conservation gains will become more secure if we can reduce the burden on local people and ensure that conservation efforts gain the legitimacy of local democratic accountability. Injustice needs to be recognized and addressed, not repeated.

Republished with permission from Mongabay.com. Read the original.