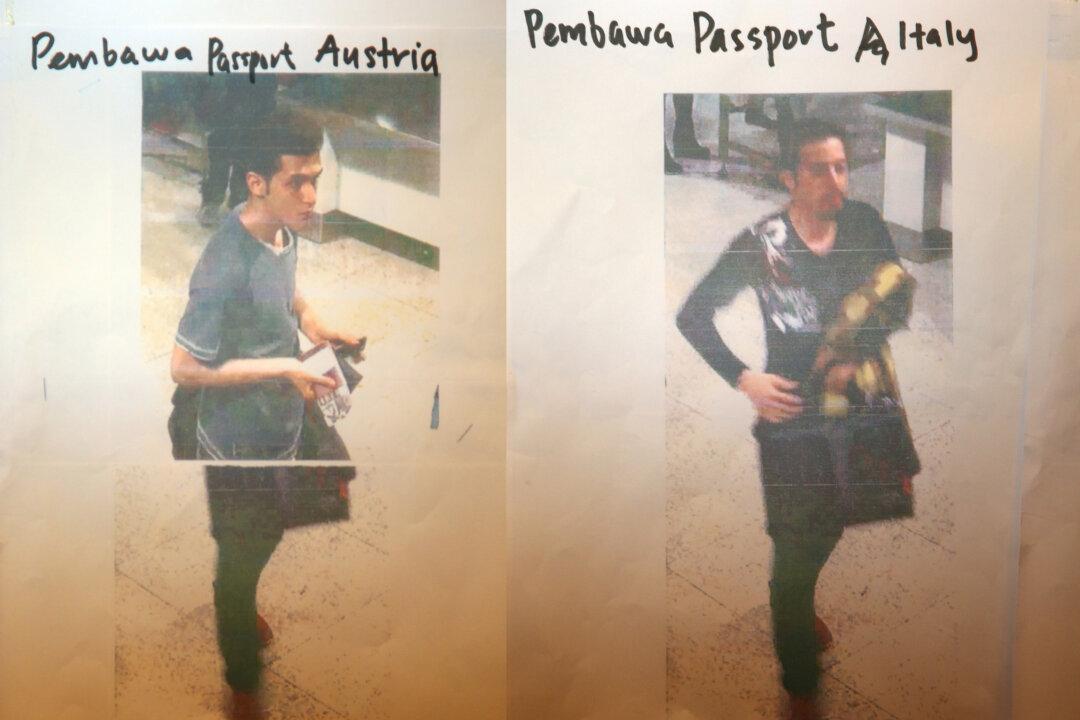

It has emerged that two of the passengers on the missing flight MH370 were travelling on stolen passports. Initially this was thought to suggest that terrorism might be involved in the disappearance, but Interpol has dismissed this notion, believing instead that the two Iranians with false travel documents were hoping to seek asylum in Europe.

This accords with my experience of refugees who are often forced to try to gain asylum with the use of forged or fake documents. This is also recognized by Article 31 of the Geneva Convention, which also states they should not be penalized for doing so. Refugees have limited choices when it comes to leaving their home country: they can either try to sneak across land or sea borders without papers, or they can buy or rent false papers and try to enter through migration controls without being detected.

States do not issue visas for those wishing to claim asylum, so there is no legal way for refugees to enter a country, unless they are prepared to wait in a camp for months and often years. Even then, they will only be resettled if they are elderly, very young, very ill, very vulnerable, or have family members in the resettlement country. This means that every year desperate people take great risks, entrusting and sometimes losing their lives, in boats or trying to climb or get around fences such as those around the Spanish exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in Morocco, or the more recently erected fence along the Evros River between Turkey and Greece, or indeed climbing into the undercarriage of aircraft.

The absence of legal gateways for refugees has created a demand for agents and a very lucrative market for forged and stolen passports, or for genuine passports with fake visas. The more money the client is willing or able to spend, the better the product. Those with sufficient money can bribe embassy staff and effectively purchase a visa. European embassies are not exempt from such practices.

Others will buy stolen passports and forgers will substitute the traveller’s photo. Some states have invested heavily in new technologies meaning that passports from fewer states can be doctored in this way, but often these are transit states. Refugees will use the forged passport to leave their home state, and try other means to get to their destination, or alternatively leave on their own passports and try to use a forgery to enter harder-to-reach states.

Assumed Identities

Over the past decade I have increasingly come across the practice of renting passports. Agents acquire stolen passports and rent them to people who look enough like the original photograph. The passport is genuine—it just doesn’t belong to the person travelling on it. The price is relatively low, because it will be collected from the traveller once they have safely arrived to be used again, and again.

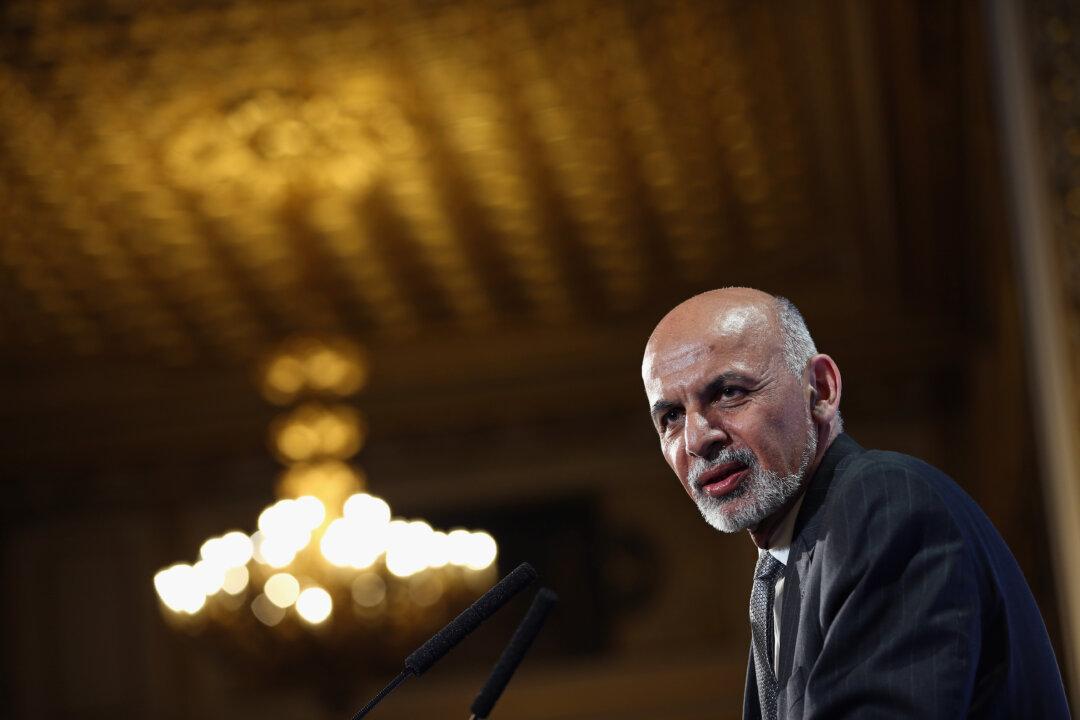

In the case of Soraya, a young Afghan woman who had been in exile in Iran for many years, her agent provided her with the passport of a Bulgarian woman and a ticket to Sweden from Athens for 3,000 euros and cautioned her not to claim asylum before his colleague in Malmo had collected the passport from her. With, according to Ronald Noble from Interpol, a billion passports unscreened each year, her success is unsurprising—and to be welcomed. Within a year she had been recognized as a refugee.

Others are not so lucky. Mahmood was given a Spanish passport by his agent and a ticket to Madrid through Istanbul. At the transit desk, collecting the boarding pass for onward travel, the airline clerk was suspicious, not because of any tampering with the passport, but because Mahmood couldn’t speak a word of Spanish. The passport was confiscated and he was deported to Kabul without being allowed to claim asylum.

Given the number of passengers moving through airports, especially hubs like New York, Heathrow, and Frankfurt, states co-opted airline staff for the Herculean task of trying to detect those travelling on inadequate or forged documents. European and other developed states increased the difficulties facing refugees by introducing Carriers Liability laws, which fine airlines, ferry, and transport companies for each passenger discovered without the appropriate documentation. Though the declared targets are “illegal” migrants, refugees, who use the same agents and travel the same routes, are also penalized.

However, once the refugee has arrived and claimed asylum, Article 31 should mean how they arrived—on a plane with a stolen passport or in a boat without any papers—is irrelevant. Inevitably, the commodification of entry to stable democracies means that those who are fleeing persecution, but who do not have contacts or resources, cannot access these precious documents. So those who are at risk at home are put at further risk en route by states that refuse to create access to their territories for refugees.

It is impossible to know how many attempt, and how many succeed, in getting through passport controls with documents not their own. What should be of greater concern is the number of refugees like Mahmood, who are prevented from reaching safety because they cannot afford a good enough fake, or any document at all.

Dr. Liza Schuster is a reader in the department of Sociology at City University London. Currently she is exploring the impact of deportation on those deported, their families and communities, and the states and societies that deport and receive them. She is in Kabul, Afghanistan, on a Leverhulme-funded fellowship. This article previously appeared in the conversation.com