Just as Alberta decides not to follow some other provinces in limiting funding for highly addictive painkiller OxyContin, Ontario First Nations are seeking government support for a potential mass withdrawal in their communities due to the discontinuation of the drug on March 1.

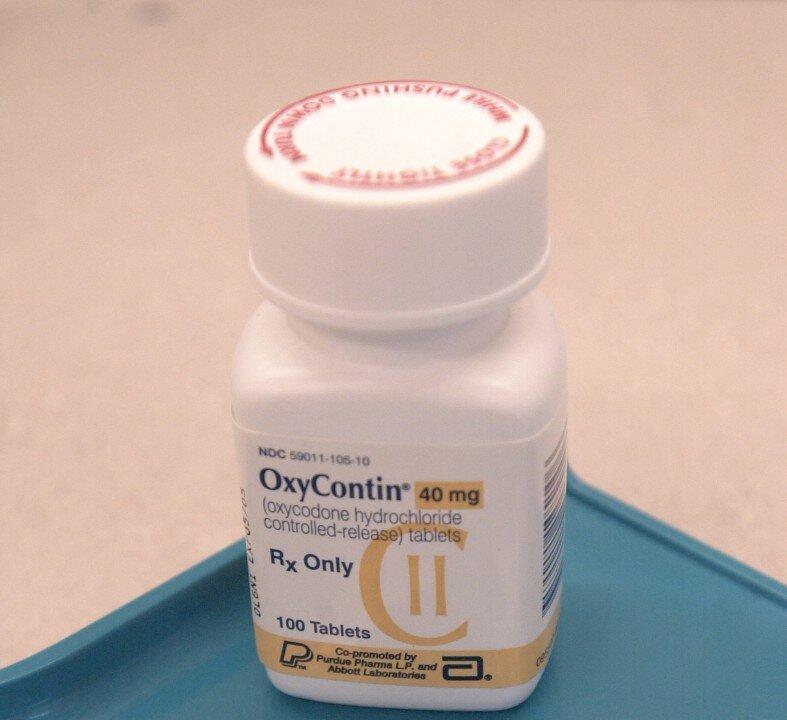

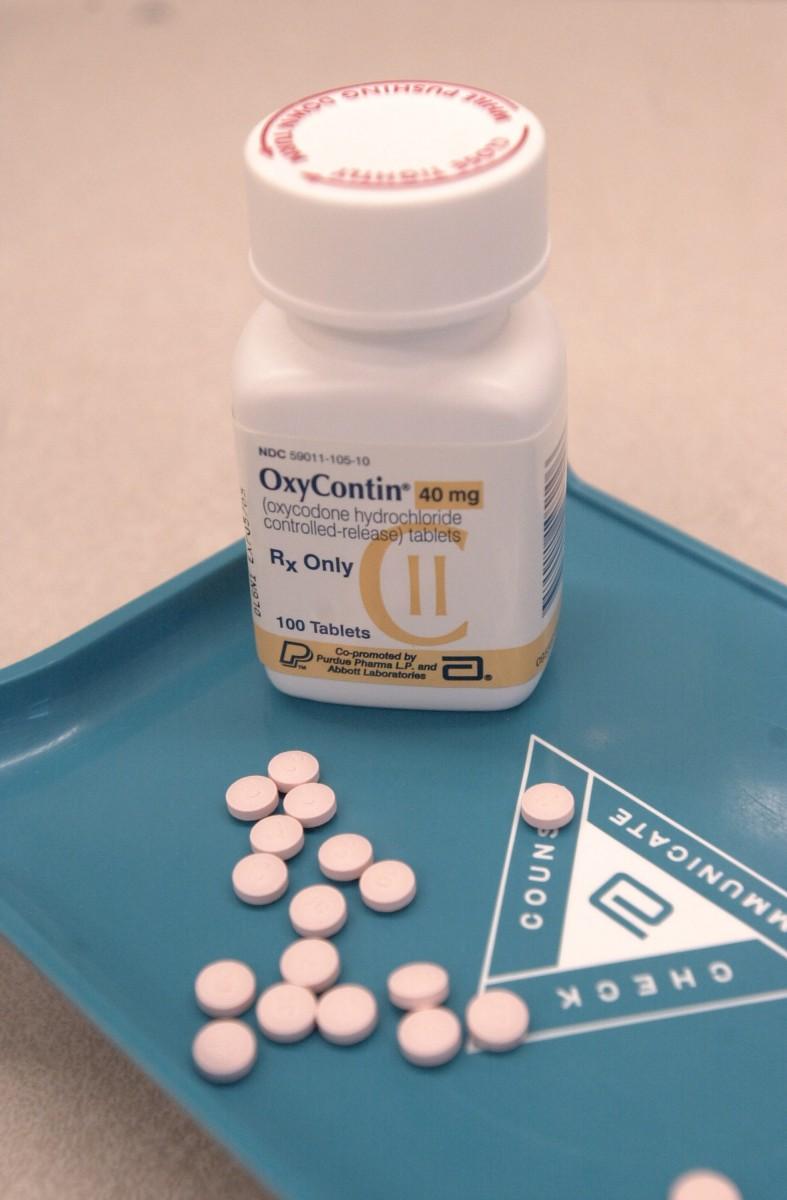

OxyContin was pulled from the Canadian market by manufacturer Purdue Pharma because of increasing rates of abuse.

It is being replaced with a new version of the drug called OxyNeo, said to be more difficult to abuse because it cannot be crushed or liquefied, making it unsuitable for injecting or snorting.

Health Canada recently announced that all “long-acting oxycodones” such as OxyContin and OxyNeo have been removed from the Non-Insured Health Benefits (NIHB) list, including for First Nations people.

Alberta has said it has no plans to delist OxyContin but will monitor the success of other provinces that are delisting it from public health benefits, such as Saskatchewan and Ontario, to see whether it is a viable solution to curbing addiction.

Alberta had the highest rate of prescription opioid use among all provinces in 2010, while consumption has climbed across the country, doubling in the past decade alone.

Some addiction experts have warned that the move could spark a public health crisis due to mass withdrawal, especially in remote First Nations communities where the drug, dubbed “hillbilly heroin,” is often used illicitly for the powerful high it provides when crushed and ingested.

Deputy Grand Chief Mike Metatawabin of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN), which represents 49 First Nations in an area covering two-thirds of Ontario, says up to 70 percent of people in some Ontario First Nations communities are addicted to OxyContin and face a health crisis when the drug is pulled.

“We have a public health catastrophe on our hands, and no one is stepping up to take responsibility to help our people,” says Metatawabin.