The costs of global terrorism on business go beyond the destruction caused in the attacks, to impact the value of brands and supply chains for products, new research shows. It can also give a competitive edge to some companies while destroying others.

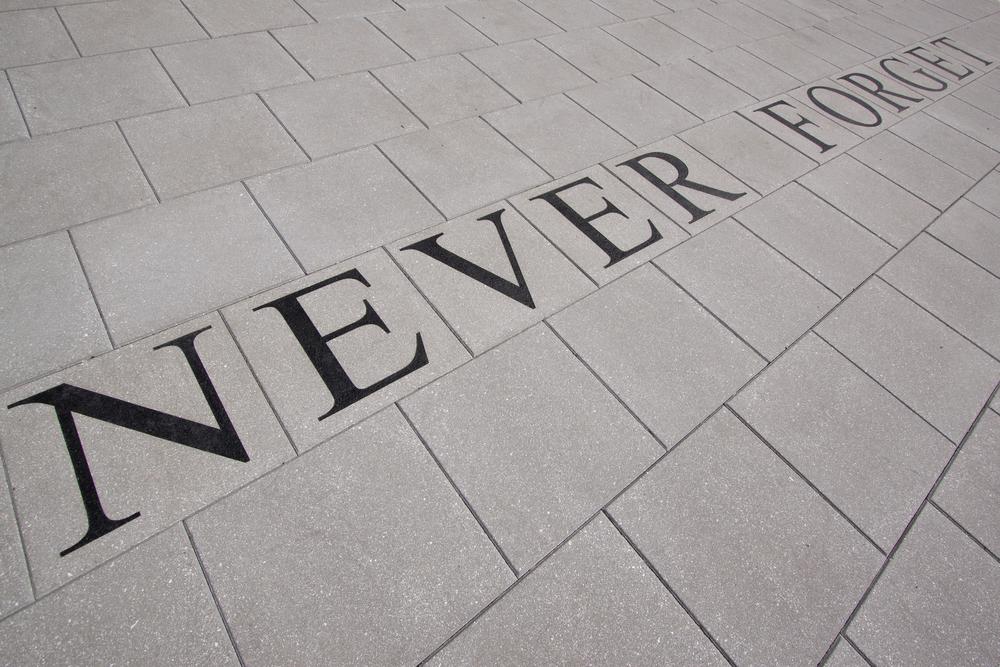

In the 15 years since the September 11 terrorist attacks, terrorism and its tragic consequences have become transnational in nature and in impact. Terrorism moved from an unquantifiable uncertainty to a risk, with an ever-increasing frequency that exceeded 70,000 attacks within the last 15 years.

Terrorism has also amplified in scale and scope. It claims more human lives and aims to immobilize societies and economies, if we let it. Our research dissects the direct and indirect impacts of terrorism of the past fifteen years.

There have been 5,367 so-called “effective” attacks recorded by the Global Terrorism Database since 2001 directly targeting businesses, with or sometimes without loss of human life. This equals, on average, 1.1 terrorist attacks each day on business by what is recorded as global terrorism.

For example, an attack on a Tunisia hotel in the Port El Kantaoui in 2015 was estimated to cost the business about £32 million, and its effects are ongoing. These attacks also impact the local, national, and often international economy. The 2008 terrorism attacks in Mumbai were estimated to have incurred a US$100 million negative impact on India’s economy through a loss of business.

The impact of terrorism goes well beyond these figures. It brings a perception of risk and uncertainty that influences consumer behaviour, delays mergers and acquisitions and impacts all stages of the international value chain.

Value Chain Impacts

Value chains, the process where a company adds value to a product through marketing, production and sales in the global fragmentation of its processes, can be severely disrupted by terrorism. For example, following the September 11 terrorist attacks, real GDP in the US shrank in the third quarter of 2001. Further OECD research has shown production costs from terrorism attacks can amount to 3% of GDP, the equivalent of a small OECD country’s GDP.

In a globalized world companies can move and reconfigure production and most other components of the value chain from one country to another. Corporate investment and contracting tends to migrate to less risky countries and suppliers or partners based there because of terrorism. This is because the costs are higher and the logistics are often more complex, requiring more management, in riskier nations.

Terrorism causes high friction and transactions costs, warehouse risks, disruptions in logistics, costs of border control and governmental regulations and much more. This makes fragmented production across borders more vulnerable.

The price paid by businesses (and society) is vast. A US Trade estimate report calculated that shipping delays associated with terrorism were equivalent to a tariff rate of 2% by 2006.

If organizations are resilient, appropriately managed and well resourced, terrorism has less impact. Organisations offset shortages and manage disruptions effectively, and diversify the physical movement of goods and labor.

Components may be delivered from various locations; some expatriates are expected to work out of the locations that are adjacent to the target market yet not based there. For example, some firms that operate in Afghanistan fly their expatriate workers from Dubai for the working week.

Companies can set up production, assembly and distribution to be structured for resilience through flexible or multiple, mobile options. At a cost, human resources management can also adapt to the challenge through new tools and revised policies.

Sales, Marketing and Brands Management

While most parts of those value chain parts are mobile (at least in principle), some are less so. Marketing and sales activities are examples of this.

There is a link between brand performance and macroeconomic phenomena, including financial crises, terrorism and warfare. This includes the perception of a brand by consumers, their engagement with the brand, and the conversation of their interest in the brand to purchasing its products or services.

Our analysis shows the overall value of the top 100 brands in the world fell by a noteworthy 5.59% from 2001 to 2002. US brand value, compared with other international brands, only recovered by 2007.

Customers fear uncertainty. Consumers of global brands react to terrorism by going local and avoiding brands originating from the countries where the attacks occur. The consumer is not prepared to pay the premium for such a brand in such contexts.

Local feels safer, though only in the short to medium term. Adapting a brand to account for these reactions from consumers takes time and significant resources. The more global terrorism strikes, the harder it gets. The more resilient the consumer and the brand is, the better.

Because companies are victim to terrorism unwittingly, a move from lean to diversified brand strategies supports resilience. One example is Toyota. Its Land Cruiser SUVs and Hilux pickup brands and products have been prominently used by some terrorist groups, so the company switched to rely on its other brands for revenue growth.

The Winners and Losers in Business

Terrorism brings advantage to some business sectors. This is apart from the obvious interrelated illegal business including drug dealing, human trafficking and more.

Some corporations have become resilient enough, often through diversification, to get some competitive advantage from their capacity to handle terrorism shocks. These companies can thrive despite (and sometimes within) hostile environments, or to cope with the costs of supply chain expansion.

Business increasingly want to set up operations with the ability to shift production. Firms locate into hostile environments to gain knowledge on how to manage people in such contexts. For example, tech companies have entered countries such as South Sudan, Yemen and Afghanistan through direct investment, such as those made by the Swedish telecoms firm TeliaSonera.

Terrorism might shock developed and well-resourced organizations, but it primarily kills the weaker ones. Larger firms are able to assess and manage terrorism as a risk. It has a frequency and increasingly detectable patterns that allow quantifying, studying and modelling.

However, small and medium sized enterprises suffer most, as they are dependent on value chains to function well and include them in the long term. These businesses also often have scarce resources.

For example a small to medium enterprise in Malaysia may contribute to a value chain that encompasses product assembly in China and sales in Japan. Businesses like this will often not survive when contracts are limited, or when the company it supplies divests or reduces its orders for the sake of spreading production or assembly to various locations.

Resilience has its price, too: yet it is lesser than that of any other option.

![]()

Gabriele Suder, Principal Fellow, Faculty of Business & Economics/Melbourne Business School, University of Melbourne. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.