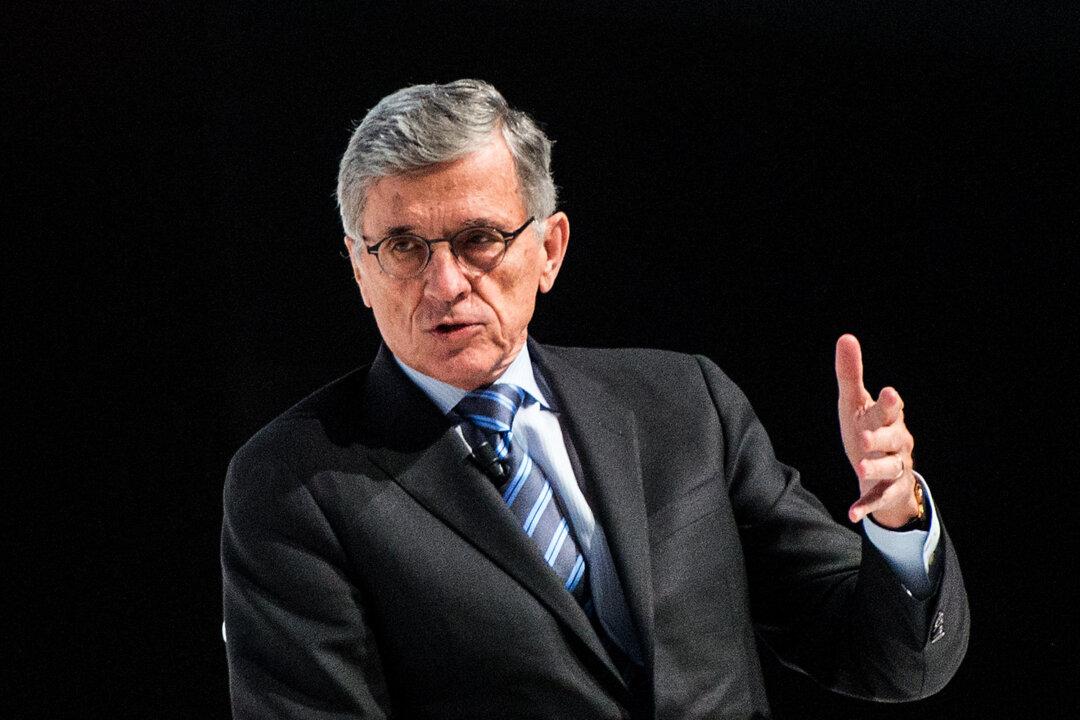

Federal Communications Commission chair Tom Wheeler said on Thursday that he opposes the idea of setting the rates for Internet service providers (ISP) and would work to set a precedent against rate regulation.

In February, the FCC voted in a controversial 3–2 decision to reclassify ISPs under Title II of the Telecommunications Act, which would subject them to “just and reasonable” practices, which some worry could be used by the FCC to set cable prices.

The impetus of the vote was to impose net neutrality rules that prevent ISPs from discriminating against different kinds of Internet traffic and offer paid prioritization of traffic, but the reclassification has granted the FCC broad powers far beyond enforcing net neutrality.

Wheeler admitted that the move would grant the FCC the authority to set rates for cable, but dismissed the possibility as unlikely, noting that the FCC has had similar control over wireless mobile voice services for over 20 years with no consequences.”