NEW YORK—A sudden plunge in the price of oil is sending economic and political shockwaves around the world. Oil exporting countries are bracing for potentially crippling budget shortfalls and importing nations are benefiting from the lowest prices in four years.

The global price of oil closed at $84.47 per barrel Thursday, down about $31, or 27 percent, from its high point for the year. Oil consumption globally is 91 million barrels per day. That means the world’s oil producing countries and companies are bringing in as much as $2.8 billion less in revenue every day — and consumers, shippers and airlines are saving a comparable amount on gasoline, diesel and jet fuel.

“The problem is that countries get accustomed to a certain level of income, and then spend,” says Edward Chow, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “It seems like a windfall at first but when it lasts long enough you get used to it.”

The global price of oil was relatively stable for nearly four years, averaging $110 per barrel. Increased production in the U.S., Canada, Iraq and elsewhere made up for declining supplies in nations such as Iran and Libya and helped meet rising global demand.

That delicate balance has been upended by a weaker global economy. Demand is slowing while production, particularly in the U.S., continues to surge.

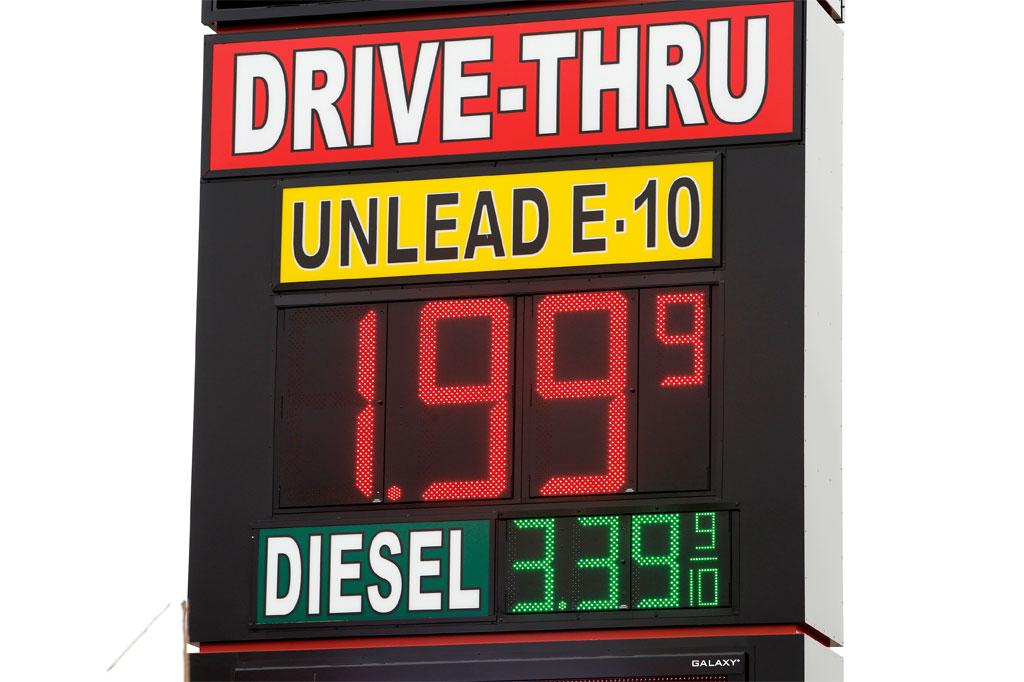

Consumer-driven economies benefit. For example, drivers in the U.S. are paying $3.16 a gallon on average for gasoline, the lowest average since 2011, giving them more money to spend.

“If this drop stays where it is that would effectively be a $600 tax credit to an average American household,” says Ed Morse, global head of commodities research at Citigroup.

In general the plunge in prices is good for those who have to buy fuel, and bad for those who sell it. But it has far wider and more complex effects on economies around the globe that are only starting to be felt.

MAJOR EXPORTERS

OPEC countries and other major exporters will feel the biggest impact. The cash-strapped governments of Russia, Venezuela and Iraq are among the most vulnerable.

Oil is cheap to produce in these countries, so they still make money at lower prices. But their government budgets are based on expectations of oil prices of $100 or more.

On Tuesday, Russian President Vladimir Putin expressed concern that lower oil prices could force the government to cut spending. Researchers at the state-owned Sberbank, Russia’s largest bank, estimate that the country needs an oil price of over $104 per barrel to balance its budget next year.

In Venezuela, the government leans heavily on oil revenue to fund spending on housing projects, community organizing and other social programs. Now, oil production is falling at a time when the country desperately needs cash. This month, the analysis firm Stratfor Global estimated that Venezuela needs oil at $110 to continue meeting its obligations.

Last week, Venezuelan Foreign Minister Rafael Ramirez called for an emergency OPEC meeting to allow member countries cut production to keep prices above $100.

Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest exporter and OPEC’s most influential member, might not rush to cut production, however, even though it would start running a deficit with oil at $85 per barrel, according to Merrill Lynch. With a large reserve fund — estimated to be $700 billion — it could withstand a longer period of lower prices.

Saudi Arabia may be interested in using lower prices to force Western oil companies to cut back on some less profitable production in an effort to secure market share.

Iraq is counting on rising revenue both from high oil prices and increasing production to help it fight the insurgency gripping the country and recover from war. Revenue may now fall instead.

ASIA

The picture is reversed in Asia, where most countries are major importers and some subsidize the price of fuels.

China is the second-largest oil consumer and on track to become the largest net importer of oil. Falling prices will provide China’s economy some relief, according to Huang Bingjie, professor from the School of Economics and Management at China University of Petroleum. But lower oil prices won’t fully offset the far wider effects of a slowing economy.

India imports three-quarters of its oil and analysts say falling oil prices will ease the country’s chronic current account deficit. Samiran Chakraborty, head of research in India for Standard Chartered Bank, also says the cost of India’s fuel subsidies would fall by $2.5 billion during its current fiscal year if oil prices stay low.

Japan imports nearly all of the oil it uses. Also, following the accident at the Fukushima Dai-Ichi nuclear power plant in 2011, the country’s power prices have risen because it has had to turn to expensive oil and natural gas to generate electricity. The recent lower oil prices help, but are a mixed blessing. They lower inflation at a time when Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is trying to raise it with his deflation-fighting “Abenomics” growth strategy.

NORTH AMERICA, SOUTH AMERICA, AND EUROPE

Low prices could eventually threaten the boom in oil production in such countries as the U.S., Canada, and Brazil because that oil is expensive to produce. Investors have dumped shares of energy companies in recent weeks, helping to drag global stock markets lower.

For now, lower crude oil and fuel prices are a boon for consumers. In the U.S., still the world’s biggest oil user, consumer spending accounts for two-thirds of the U.S. economy, and lower energy prices give consumers more money to spend on things other than fuel.

The same is true in Europe. Christian Schulz, senior economist at Berenberg Bank, says that a 10 percent fall in oil prices would lead to a 0.1 percent increase in economic output. That’s meaningful because the 18-country currency union didn’t grow at all in the second quarter.

From The Associated Press. AP Writers Hannah Dreier in Caracas, Youkyung Lee in Seoul, Christopher Bodeen in Beijing, Muneeza Naqvi in Mumbai, Aya Batrawy in Dubai, Elaine Kurtenbach in Tokyo, David McHugh in Frankfurt and Nataliya Vasilyeva in Moscow contributed to this story.