WASHINGTON—The practice of fact-checking politicians’ claims has become a highly popular feature in today’s newspaper. Originating with American journalists, it has become an international movement in journalism.

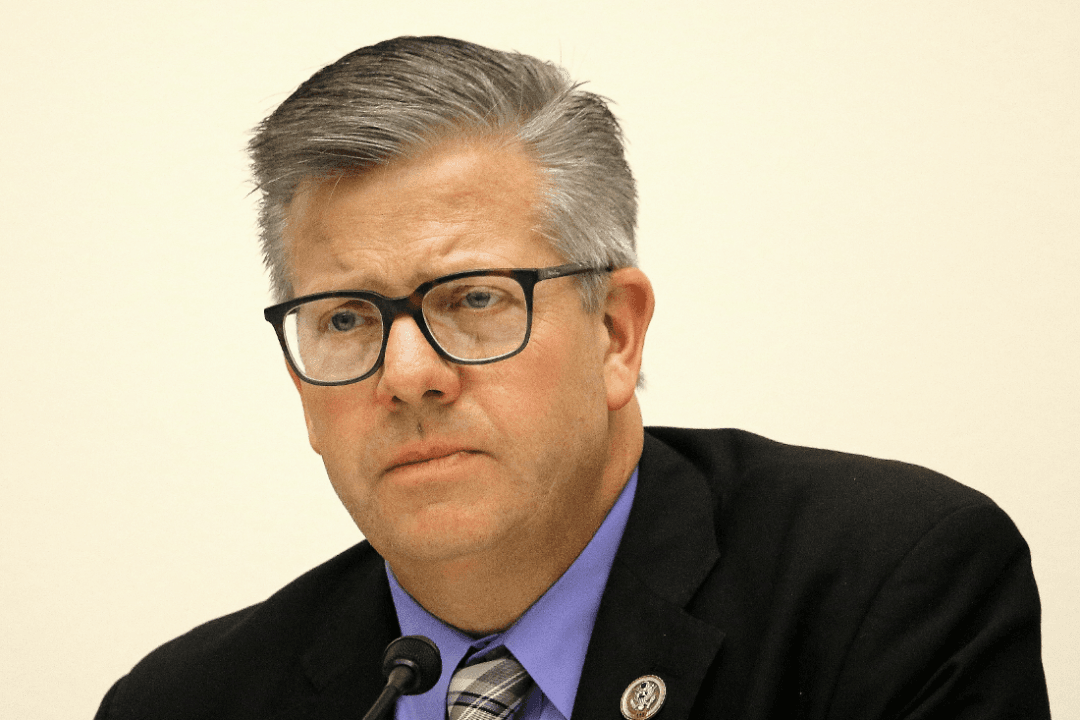

On April 15, two of the best known fact-checkers in the nation appeared at a forum, “Who’s Afraid of the Fact-Checker?”, at the Woodrow Wilson Center, to speak candidly on their experiences of fact-checking, and their perceptions on how their fact-checking is affecting politics in America.

Fact-checking has become increasingly popular overseas. Now there are about 80, said Glenn Kessler, who manages the Washington Post’s The Fact Checker.

“Frequency of fact-checking stories increased by more than 50 percent from 2004 to 2008, and by more than 300 percent from 2008 to 2013,” said Jane Elizabeth, senior research project manager for the American Press Institute (API), using data conclusions from API’s Fact-Check Project.

"[Fact-checking] is growing but there aren’t enough news organizations fact-checking, especially at the local level,' said Elizabeth.

In the 2014 election, “fact checking certainly became part of the conversation,” states the Washington Post website for fact checking. When it was to their advantage, politicians would use fact check articles and ratings to enhance their status and knock down their opponents in what fact check analysts call “weaponizing” fact checking.