Though further environmental assessment remains, Exxon Mobil agreed in January to pay $1.6 million for damages from last July’s ruptured pipeline, which spilled over 1,000 barrels of oil into the Yellowstone River 20 miles upstream from Billings, Montana. From the initial surveys of the area, oil was visible 45 miles downstream from the broken pipeline.

“We got to what we could of the really bad stuff in the beginning. But for further cleanup, we would’ve just done more harm than good by mowing down trees and creating new roadways to get into the deeper areas,” said Richard Opper, the Director of Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ),

Directly after the spill, major issues concerning the impact on local drinking water and air were addressed. According to the DEQ, downstream water intake valves were quickly notified and closed. Subsequent testing has confirmed no residual oil in municipal water systems.

“The toxins in crude oil volatilize quickly, sometimes within hours. These were restricted within a couple days,” says Opper.

The effects the spill has had on the wildlife are still being studied however.

The state of Montana, the EPA, and other federal organizations have overseen the cleanup efforts to ensure that Exxon is held accountable.

The oil giant has been quick to acknowledge responsibility and has agreed to reimburse all costs, including all past and future cleanup related to the spill. Exxon may be required to pay more beyond the $1.6 million after the damage to the habitat is more fully understood.

Awareness About Pipeline Safety

While the spill is a black mark for both Exxon Mobil, and more literally for the Yellowstone River, some good has come out of it, according to experts involved in the cleanup.

“The spill opened the eyes of the country to pipeline safety. It led to the creation of the Pipeline Safety Council,” says Mary Ann Dunwell, the Public Information Coordinator for the Remediation Division of Montana.

The Pipeline Safety Council is responsible for major inspections and for identifying potential problems in oil pipelines. Other pipelines around the United States have been rebuilt or re-drilled since the council’s creation, and the rebuilt pipeline under the Yellowstone River now lies closer to 70 feet underground, compared to the mere 6-8 feet previously.

“We now know a lot more about pipeline systems and how to identify future problems,” says Opper.

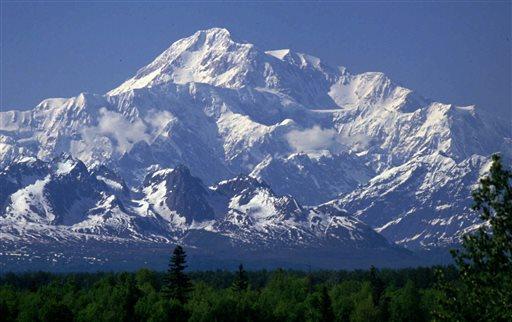

Exxon’s biggest disaster was in 1989, when the tanker Exxon Valdez spilled an estimated 11 million gallons of crude oil across 1,300 miles of coastline in Alaska’s Prince William Sound. To this day, there is evidence of continuing damage in some areas where oil remains.