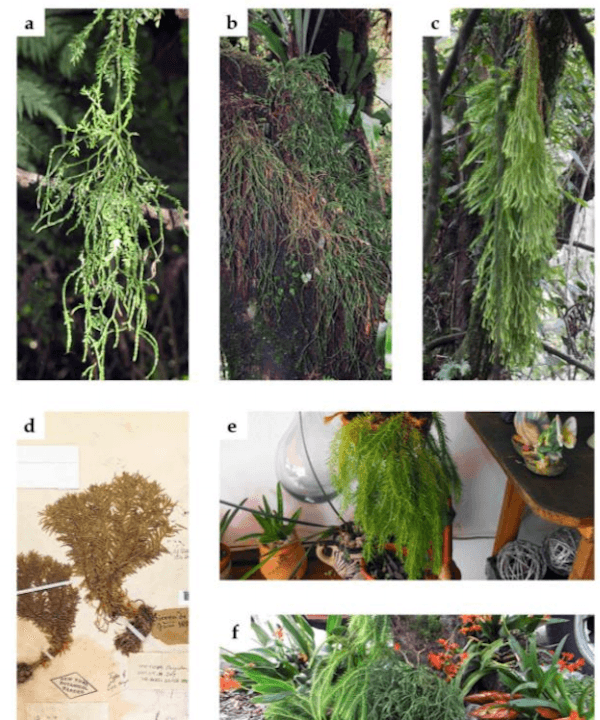

In Mexico’s rainforests, club mosses – fern-like plants that resemble the branches of pine trees - are in trouble.

All nine species of the club moss genus Phlegmariurus found in the state of Veracruz in eastern Mexico are at risk of extinction, according to a new study published in the journal Tropical Conservation Science. One of these species, P. orizabae, has not been recorded in the wild since 1854.

A team of researchers, from the University of Veracruz in Mexico, examined 173 herbarium specimens and digital photographs of Phlegmariurus club moss species collected from different parts of Veracruz between 1824 and 2014. Using these, the researchers set out to evaluate the current geographical distribution of the club mosses and their conservation status.

The team overlaid the species’ locations on GIS layers of land-use, vegetation, and climatic variables for the region, and then modelled their potential distribution. Their analysis revealed that the club mosses – most of which are “epiphytes” that grow on trees - occur in the central and southern parts of Veracruz between 120 to 2,500 meters (390 to 8,200 feet) in elevation. These regions mostly have humid montane forests, with some tropical humid and pine-oak forests. And these areas meet the preference of Phlegmariurus species, the authors write, since the species require special light conditions and are sensitive to prolonged dry periods.

But in Veracruz, as well as in other parts of Mexico, deforestation and conversion of land to farms and pastures are reducing and degrading these ecosystems, the researchers write. For instance, about 30 percent of the herbarium specimens collected between 1924 and 2000 were from forests that were logged, the authors note. This means that many of the older Phlegmariurus habitats are now lost.

Such deforestation can harm club moss in a number of ways. It exposes the shade and moisture-loving epiphytes to the harsh drier and warmer conditions of disturbed and secondary forests. It also deprives them of mature host canopy trees on which they live. Moreover, the team’s analysis of the conservation status of the Phlegmariurusspecies showed that, within Veracruz, all the nine species are in some category of extinction risk based on IUCN criteria. In fact, one species - P. orizabae – is known only from one collection made in 1854.

“It is possible that land-use change and habitat fragmentation in Veracruz may have resulted in the extirpation of this species in Veracruz,” the authors write. But they also question whether a greater collection effort in the region can help re-discover this species in the future.

Veracruz: plant diversity hotspot

Veracruz has rich diversity of both plants and animals, many of which are endemic to the state. The Los Tuxtlas and Uxpanapa regions in southern Veracruz, from where many of the Phlegmariurus specimens were collected, are particularly rich centers of endemism. For instance, these mountainous regions have been identified as an Endemic Bird Area by BirdLife International.

Some endemic birds found in Veracruz’s moist forests include the endangered Tuxtla quail-dove (Zentrygon carrikeri), green-cheeked amazon (Amazona viridigenalis), Tamaulipas crow (Corvus imparatus), and crimson-collared grosbeak (Rhodothraupis celaeno). The forests are also home to two endemic rodents, and threatened mammals like the jaguar, ocelot, jaguarondi, and coati.

But despite its rich biodiversity and high endemism, Veracruz has the highest loss of forest cover in Mexico, the authors write.

According to WWF, about 1.8 million hectares of Veracruz’s 6.9 million-hectare area was logged for timber and conversion to agricultural and pasture lands from 1900 to 1987. Then between 1984 and 2000, about 36 percent of the state’s remaining forest cover was lost, the authors write.

From 2001 through 2012, the state lost nearly 250,000 hectares of tree cover, at an average rate of 20,000 hectares per year, according to Global Forest Watch. Currently, less than 9 percent of the original natural vegetation remains in the state. And these forested areas occur in small, isolated fragments, the authors write.

Los Tuxtlas, too, has suffered large-scale deforestation since the 1970s. A study in the early 1990s found that the annual deforestation rate between 1967 and 1987 was over 4 percent. Despite being formally protected as Biosphere Reserve since 2006, deforestation continues. Between 2001 and 2012, the Biosphere Reserve lost over 2000 hectares of tree cover, according to Global Forest Watch.

Fragmentation of the Los Tuxtlas forests, combined with hunting, has even resulted in the local extinction of some birds like king vulture (Sarcoramphus papa), harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja), and scarlet macaw (Ara macao).

The destruction of primary forests in Veracruz has also resulted in the decline of other epiphytes. For instance, six epiphytic orchid species in the state have been driven to local extinction. Many epiphytes, including those belonging to the Phlegmariurus species, are also being harvested from their natural habitat and sold in local markets of Veracruz and other states like Oaxaca for ornamental purposes, the researchers write.

Moreover, they add that the “species of Phlegmariurus in Mexico are very poorly represented in regional or national herbaria, and some species are represented by only a few specimens collected decades ago, as is the case with P. cuernavacensis and P. orizabae in Veracruz.”

Epiphytes like the Phlegmariurus species inhabit undisturbed forests, and are usually absent from disturbed or secondary forests. These species could thus act as good bioindicators of forest health and its biodiversity, according to the authors, making them detectors of priority conservation areas.

The first step of protecting these threatened epiphytes is to conduct more detailed surveys, the authors note. Insight into their distributions as well as the discovery of endemic or endangered plants could help bolster the creation of new reserves in these regions, they add.

“In addition to in situ conservation, it is important to raise awareness among plant collectors and the public about Phlegmariurus and epiphytes in general,“ they write. ”Moreover, environmental education, management programs and regulations should be applied in order to promote the sustainable harvest of Phlegmariurus as well.”

Citations:

- Armenta-Montero, S., Carvajal-Hernández, C., Ellis, E., and Krömer, T. 2015. Distribution and conservation status of Phlegmariurus (Lycopodiaceae) in the state of Veracruz, Mexico. Tropical Conservation Science Vol.8 (1): 45-57. Available online: www.tropicalconservationscience.org

- Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland, Google, USGS, and NASA. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on March 25, 2015. www.globalforestwatch.org.

- UNEP-WCMC, UNEP, and IUCN. “World Database on Protected Areas.” Accessed on March 24, 2015. www.protectedplanet.net.

This article was written by Shreya Dasgupta, a contributing writer for news.mongabay.com. This article was republished with permission, original article here.